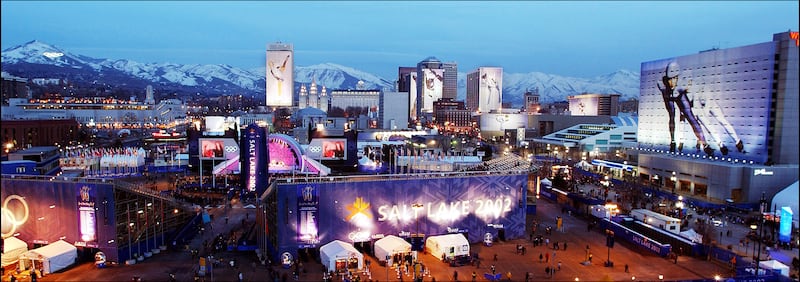

The moment that then-Utah Gov. Mike Leavitt fully understood the impact of hosting the 2002 Winter Games came hours before the Feb. 8 opening ceremonies at the University of Utah’s Rice-Eccles Stadium introduced the Beehive State to more than 2 billion TV viewers around the world.

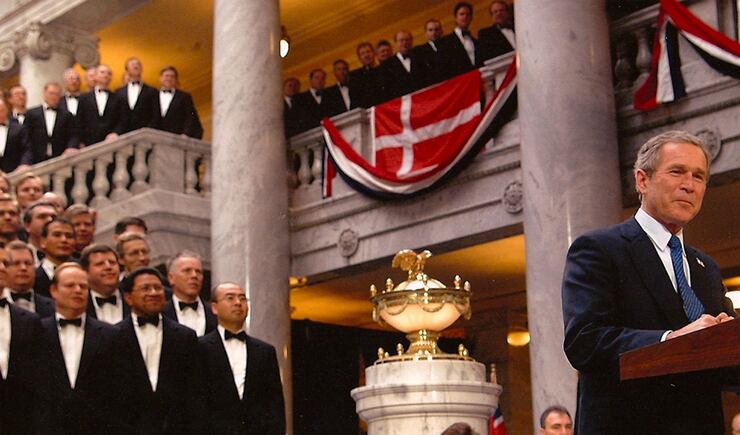

He was in his office at the Utah Capitol with then-President George W. Bush, who’d brought Secretary of State Colin Powell and other key members of his Cabinet to Utah, discussing topics like the 9/11 attack against the United States just a few months earlier and the war to come in Iraq.

A sitting president had never before visited the Utah Capitol, but here was Bush, a friend since his days as governor of Texas, and he and his team weren’t just making small talk between an earlier meeting with leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and a pre-Games ceremony in the Capitol rotunda.

“That’s the point, that Utah was, at that moment, the center of the world,” said Leavitt, who would later go on to join Bush’s Cabinet and is now the president of The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square that performed in both the rotunda and the stadium that day.

Not that there was really time to savor having not only the leader of the free world but a long list of other dignitaries, including then-secretary general of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, gathered at the Capitol for the ceremony to celebrate Utah as an Olympic host.

The 17 days of the 2002 Winter Games were filled with “glorious moments, but it was also a period of intense execution,” the former governor said, recalling late-night meetings to go over the next day’s packed schedule. “Every day was a series of activities that had to be performed and done well. Because this was our moment.”

While Leavitt was racing between appearances and dealing with issues that surfaced, such as an anthrax scare at the Salt Lake City International Airport, the man who would go on to become Utah’s governor 18 years later had just moved his family back to the state after law school to serve as a clerk for a federal judge and couldn’t afford tickets to attend any events.

But with the federal courthouse closed during the Olympics for security reasons, now-Gov. Spencer Cox said he and his family were able to head from where they were living in Fruit Heights to downtown Salt Lake City to soak up the sights and sounds of streets crowded with international visitors.

“We would go down and just walk around town, and just talk to people and listen to conversations, walk though the plaza and just had an incredible experience there during that time,” Cox said, seeing firsthand what he called the city’s transformation into a “kind of a melting pot. ... There was just such an energy.”

Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall has similar memories of the 2002 Games.

“I was living on 3rd Avenue and an undergraduate newlywed. The access to experiencing the Games as a young resident in the city was the sweetest part. You could bundle up and put your Roots hat on and walk downtown to feel the world around us,” Mendenhall said.

The mayor recalled the “positive humanity” the Olympics brought to Salt Lake City two decades ago.

“Everyone was so excited to be there. The art, the music and the enthusiasm was so palpable everywhere we went. So although I was not in a place in life where I could buy expensive tickets, I still very much felt like I had an Olympic Winter Games experience just by basking in the energy of the city over those couple weeks,” she said.

Utah volunteers hailed as 2002 ‘champions’

Backers of bringing another Winter Games to Utah as soon as 2030 say by then, an entire generation will have missed out not only on experiencing such a close connection with the rest of the world at home, but also the pride — and potential practical benefits — of showing off what the state has to offer.

At the top of that list are Utahns themselves, said Fraser Bullock, the president and CEO of the Salt Lake City-Utah Committee for the Games expecting to bid for the 2030 Winter Games — and the chief operating officer of the 2002 Olympics under now Utah Sen. Mitt Romney.

“The reason why it was a magical period, at the heart of it, was the people,” Bullock said, especially the thousands of Utahns who volunteered over the 17 days of the Olympics and the Paralympics for athletes with disabilities that followed, identified by their brightly colored parkas and other Games gear that some continue to wear proudly 20 years later.

Every Olympics is remembered for the performances of the athletes. In 2002, Team USA earned a record 34 medals including gold and silver for speedskater Derek Parra, who worked at a Home Depot in West Valley City while training, and gold for bobsledder Vonetta Flowers, the first for a Black Olympian in a Winter Games.,

But when the late International Olympic Committee President Jacques Rogge declared Utah had put on “superb” Games, he singled out the volunteers, many fluent in languages like Rogge’s native Flemish that they learned as missionaries for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“You are, with the athletes, also the champions of these Games,” Rogge told volunteers during the Games’ closing ceremonies, also at Rice-Eccles Stadium. “Your generosity and profound kindness have warmed our hearts. You were marvelous.”

Romney said both the volunteers and the nearly 2,400 athletes from 78 nations that competed in Utah “were very moving and inspiring.” He remembers being “literally moved to tears in my eyes” when almost 50,000 Utahns immediately signed up to fill the less than 25,000 volunteer positions available.

“We didn’t know whether anyone would show up to volunteer. After all, it was going to be cold, you’re going to be outside and you got no tickets.” Romney recalls how some volunteers even took it upon themselves to raise money to buy equipment for a few Olympic and Paralympic athletes who showed up with outdated gear, like wooden skis.

The volunteers, he said, were “so warm, inviting, cheerful, can-do. We Americans are typically very judgmental, ‘No, you can’t do that. You’ve got to follow the rules.’ That was not the way we were at all. Our people were really friendly and happy and delighted to show people a good time.”

Even now, Romney said he’ll occasionally spot someone on a Utah ski slope in one of the red, blue, green or yellow volunteer parkas.

“I make an effort to go up to them and say hi, because it’s like being part of a very special group of people. I feel a real affinity to those that said, ‘Hey, I’m going to give 17 days to the Olympics or to the Paralympics.’ It’s very touching,” he said.

“They feel the same way. There’s a real kinship among the people who helped produce the Games.”

Bullock, who has remained involved with the IOC over the past two decades, helping to oversee the 2010 Winter Games in Vancouver, Canada, said he continues to hear about the “friendliness and devotion” of the Utah volunteers from colleagues around the world.

“It really stood out to them, how friendly our people were and then the devotion of their hard work,” Bullock said, citing an attrition rate among the 2002 volunteers of less than one-half of one percent from the beginning of the Games to the end, compared to 17% of Atlanta’s volunteer force during the 1996 Summer Games.

No longer ‘close but never there’

The recognition that Utah could stage a worldwide event so successfully — the Games’ economic impact is valued at more than $6 billion according to a 2018 analysis by the U.’s Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute — burnished the state’s reputation internally as well as externally, Cox said.

Utah’s strong economy, low unemployment and other strengths that make the state stand out nationally as the COVID-19 pandemic enters a third year all follow “a straight line” from 2002, the governor said.

“I don’t think that happens without the Olympics. I think it put us on a map,” he said, adding, “It also had an impact on the psyche of Utahns. ... We had this kind of feeling of always being close but never there” until what he called the state’s inferiority complex was finally overcome 20 years ago.

The sense that Utah deserved a place on the world stage didn’t come easy, even after Salt Lake City was selected over cities in Canada, Sweden and Switzerland by the IOC as an Olympic host, fulfilling a decadeslong quest that saw a narrow loss to Nagano, Japan, for the 1998 Winter Games.

Just a few years after winning the bid for 2002, revelations that Salt Lake City tried to buy the votes of IOC members with cash, gifts and scholarships ignited an international scandal that led to a federal criminal case that ended in acquittal as well as an overhaul of both the bid process and the Salt Lake Organizing Committee.

Romney, a Boston venture capitalist who earned his undergraduate degree at Brigham Young University, was brought in as the new SLOC boss to save the Olympics by Leavitt and other Utah leaders. Bullock, Romney’s hand-picked No. 2 at the organizing committee, credits him with restoring trust in a Salt Lake City Games.

“He was so good at instilling confidence in people,” Bullock said of Romney, understanding it would take putting on a spectacular event to emerge from the shadow cast by the scandal. “Yes, maybe we started in a very difficult place, but over time people began believing, ‘Wow, we can really do this, and do this really well.’”

That belief was challenged on Sept. 11, 2001, when terrorist attacks against the United States killed thousands, bringing down the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City near where the SLOC had scheduled an Olympic torch relay event before postponing it a day so Romney could be in Washington, D.C., to lobby Congress.

“It tested us. It tested our people. It tested our planning. It tested our capabilities,” Bullock said of hosting what was the first major international event held after 9/11, drawing hundreds of thousands of athletes, officials, spectators and others to Utah from around the globe.

Organizers quickly went to work on what was now seen as the “Security Games,” ramping up measures “to compensate for the tragedy that had struck our country and the world. And through that continued hard work, we were able to feel very confident that we would be able to keep people safe,” he said.

There’s little doubt the most memorable moment from the 2002 Winter Games came when a torn American flag recovered from the World Trade Center was solemnly carried into Rice-Eccles Stadium by U.S. Olympians escorted by New York City police and firefighters during the opening ceremonies.

“When you saw how it brought people together, it really was part of the healing process,” said Jeff Robbins, president and CEO of the Utah Sports Commission and a member of the bid’s executive committee. “All of the geopolitical things that were going on at the time, it just seemed like there was a break and we came together.”

Stark differences in Beijing

While there are a number of activities planned to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the 2002 Games including relighting the Olympic cauldron at Rice-Eccles Stadium on Tuesday, the kickoff of Utah’s bid to bring the Olympics back won’t come until sometime after the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing that began Friday amid controversy.

Romney said he’s not worried that Utah’s 20th anniversary celebration will be overshadowed by the issues plaguing Beijing, including China’s human rights record, state-backed cybersecurity threats that have resulted in Team USA advising athletes to leave their phones at home and, of course, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

“The difference between the Chinese volunteers dressed in hazmat suits and the cheerful people of Utah could not be more stark,” he said, noting that more than a third of the American athletes in Beijing, 75 of 223, have ties to Utah. Unlike Beijing, where the snow is human-made, Romney said Utah is a center for Olympic winter sports.

The senator led the push for the diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Games to protest China’s treatment of religious and ethnic minorities that was announced in December by President Joe Biden. The United States was joined by several other countries, including the United Kingdom and Australia in the boycott, which does not affect athletes.

“I was concerned that China would use the Olympics as another propaganda platform. I don’t think that’s working like they hoped it might. The stories are getting out about the restrictions placed on athletes in terms of bringing phones or possibly saying something critical about China,” Romney said. “That’s sending a message.”

China’s extreme “zero tolerance” policy toward COVID-19 means even tighter restrictions for participants than the 2020 Summer Games in Tokyo that were delayed for a year and held in 2021 due to the virus. Utah’s Olympic bidders had to cancel plans to head to Beijing at the last minute after the IOC scrapped an observer program for bid cities.

Other bidders include Vancouver; Sapporo, Japan; Barcelona, Spain and the surrounding Pyrenees mountain region; and Ukraine. The U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee that chose Salt Lake over Denver three years ago to bid for a future Winter Games only recently committed to the possibility of Salt Lake City hosting in 2030.

What hosting again means for Utah

Another Winter Games in Utah would not be without risks, but supporters say there’s more than new memories to be made by bringing one of the world’s largest sporting events back to the state. The current budget is $2.2 billion in 2030 dollars, money anticipated from selling sponsorships, TV rights and tickets — not taxpayers.

Robbins said the economic impact of other winter and summer sport competitions held in the state since 2002 is approaching $3 billion, an “incredible and meaningful number” that would get a big boost from a second Olympics in Utah, as would the chances of Utah attracting a national football, baseball or hockey team.

What Mendenhall is looking forward to are the infrastructure investments that come with an Olympics. For example, she said although the U. is expected to once again be the site of athlete housing, a new “tiny home” community could be used for media or other Games visitors before becoming housing for people experiencing homelessness.

Cox has a different take on why Utah should host another Winter Games.

“I have thought a lot about it. We do need a narrative,” the governor said, suggesting that Utahns should tap into “part of our core” by shifting the focus to giving back to an Olympic movement that has seen its share of struggles in the past two decades, particularly when it comes to containing costs.

“We can now show the rest of the world how to do a modern Games,” he said, saving money and resources by utilizing venues built for 2002, like the Utah Olympic Oval speedskating track in Kearns that continues to be used for world-class competitions.

“We don’t do it to gain something,” Cox said. “We do it because it’s a good thing. We do it because it’s something that we need. It is an opportunity to help heal the nation and heal the world, and an opportunity to show giving back is a good thing. It’s a reward in itself when we’re helping others and blessing the lives of others.”

Romney said in 2002, Utahns “felt we had served the world in a remarkable and impressive way and felt good about that.”

The Olympics, he said, changed everyone involved, including him. Had he he not headed up the 2002 Games, Romney said he never would have successfully run for governor of Massachusetts, later becoming the Republican Party’s presidential nominee in 2012, before returning to Utah and being elected to the Senate in 2018.

Volunteers “met people they would never have met otherwise. We normally associate with people that are in our own neighborhood, in our own faith, in our own social clubs. In this case, we broke all those barriers and people found they really liked one another. So I think we were really united when this was over,” Romney said.

“It’s even more needed today because American society is more divided today and bringing people together again would have another unifying effect,” he said. “Now, I also think we would produce superb Games both economic — which is important, by the way — as well as Games with heart and passion. That’s what we do in Utah.”

What could have been

When the latest bid effort began in earnest a decade ago, the hope was that Salt Lake City could host the 2022 Winter Games. The USOPC, however, was after a Summer Games for the United States, and didn’t back the long-shot bid. Besides, many believed a European city would be chosen.

But by the time the IOC chose a host city in 2015, only Beijing, which had just hosted the 2008 Summer Games, and Almaty, Kazakhstan, were still in the running after several European cities, including Oslo, Norway, dropped out of the race due to a lack of support at home.

Utahns vying for 2022 had thought there might be a chance the IOC would turn to them but were disappointed.

Now, though, Bullock acknowledges “we were fortunate to not have had the opportunity to bid on those Games because managing through COVID right now would be very challenging. It would not allow us to create the complete experience of the Games.”

Another longtime member of the Utah bid effort, Robbins, said the state would have pulled off a Winter Games despite COVID-19 thanks to the “Utah way,” an approach to dealing with difficult issues rooted in the state’s settlement by the Latter-day Saint pioneers that centers around civility and collaboration.

That’s “the way we all do things here, just like in 2002 with 9/11.” Robbins said, adding that holding an Olympics during a pandemic ”certainly wouldn’t have been the preferable way to do it. But one thing that we do have, is a very, very good ability to call an audible and adjust and problem solve.”