He started numbering his white socks on the toe with a marker to keep them from getting mixed up. He lined up all the tools in the garage. He went ballistic after waking from a Sunday nap to find the lasagna cleared from the table. He rode his Harley-Davidson to San Francisco on a whim to have dinner. He thought about putting a gun in his mouth.

Retired Utah National Guard Lt. Col. Craig Morgan went to the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001, as one person and walked away from the searing events of that day as another. What he saw and heard and did and smelled after a hijacked airliner-turned-missile smashed into the seat of U.S. military power profoundly changed him.

It took him years to figure out there was a problem, and it was him.

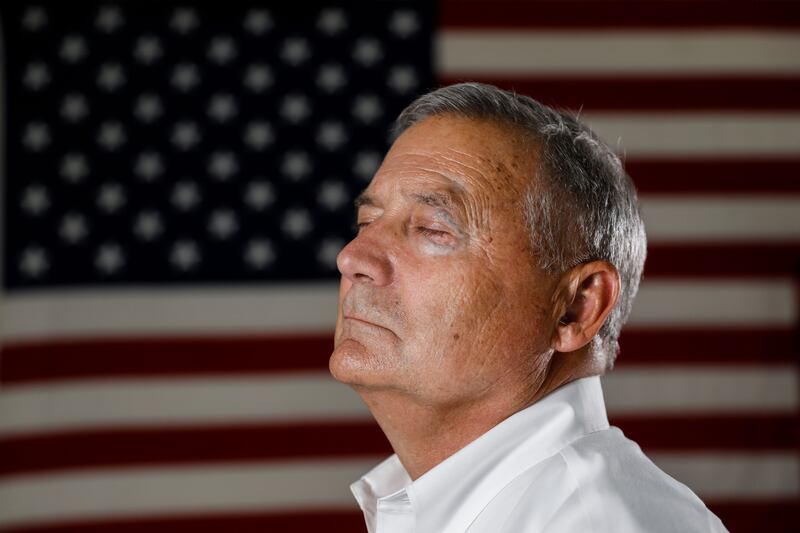

Seated on a chair in the front room of his South Jordan home, Morgan, 68, recounted his 9/11 experience in detail a few days before the 20th anniversary of the worst terrorist attack on American soil. He’s dressed in white dress shirt with the sleeves rolled up, jeans and lizard skin cowboy boots. Plaques from his military service and photos, including one of him with Evel Knievel at Sturgis, adorn the walls.

Several freshly pressed shirts are draped over another chair. A small travel bag sits on the floor. He’s headed to Oregon.

Morgan grabs a red, heart-shaped pillow from the couch. It is now the Pentagon. Side, side, side, river, where it hit.

The then-48-year-old public affairs officer was walking to the south entrance of the Pentagon for a press conference when the jet smashed into the west side. He was running late because he’d been watching the horror in New York on TV. He figures he would have been walking in the hallway where the plane hit had he been on time. He managed a quick phone call to his wife, Tammy, before cell service jammed up.

Other than a groundskeeper, Morgan was the first person on the scene. Heavy smoke poured from a gaping hole in the building. He calmed the stunned groundskeeper. He tried to corral a woman who wanted to run inside to look for her sister. He saw a man, possibly a lieutenant colonel like him, whose bloodied hands appeared to be without fingers carrying people from the building and going inside for more. He then watched the wall collapse.

“I didn’t see him anymore after that,” Morgan said.

As people calmly, even orderly, streamed outside, he directed them to the shelter of a freeway overpass. Trained as a paramedic, Morgan treated broken bones and cuts using shirts torn into slings and bandages. Blood stained his green Class B uniform and became sticky on his ungloved hands.

Two F-16s buzzed the Pentagon, eliciting not sighs of relief but a collective cheer amid the roar of the engines.

His five or six hours on scene seemed like 30 minutes.

“Oddly, in my mind, I was never afraid. I was never afraid that I was going to get injured or killed or that somebody was going to shoot at me,” Morgan said.

As the building smoldered into the night, the air smelled of burning flesh and burning hair. He said he later learned the World War II-era building was insulated with horse hair. Strangely, people returned to work the next day. Morgan found himself in the Pentagon courtyard where he saw what he initially thought were firefighters sleeping. They were bodies covered in sheets.

One of 13 Utah National Guard members on a staff trip to Washington, D.C., Morgan and his group tried to figure out how they were going to get back to Utah. Because they were traveling with a two-star general, the Marines provided a 727 to fly them home, complete with an F-16 on each wing. He drifted off to sleep as he looked out the window.

Morgan pulled into his then-Millcreek-area neighborhood to see Boy Scouts had lined the streets with American flags.

“That’s when I started to cry,” he said.

Morgan worked another five years before ending his nearly 35-year military career in January 2006. Suddenly, he had nothing to occupy his mind. And the demons moved in. Unwanted intrusive thoughts took over. He screamed in his sleep. He had nightmares.

It was always the same scenario, but different situations: separated from his family, bad guys between him and the family, and he couldn’t get to them.

Combined with his short fuse, taking off on his Harley, his newfound obsessive-compulsive behavior and a host of other ingredients made for a toxic stew. By August, Morgan’s wife, Tammy, couldn’t take it anymore. She delivered an ultimatum: Get this fixed or I’m filing for divorce — tomorrow.

Morgan couldn’t understand it. In his head, he was up for father of the year.

They agreed to see a counselor. “I’m sure he would say, ‘Lady, you got no idea how good you have it.’ But it didn’t turn out that way,” he said.

Morgan was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

A person with PTSD has difficulty recovering after experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event. It may last months or years, with triggers that can bring back memories of the trauma accompanied by intense emotional and physical reactions. For some, it never goes away.

The only ones who can really understand how someone with PTSD thinks or feels is another person with PTSD, Morgan says. People who don’t have it, don’t have the full picture of what the victim goes through. But those who experience it can talk to each other openly, freely. They can even joke about it because they know the other person gets it.

“I think the most difficult thing is that there’s not a lot you can do to help them, just listen to them and understand that sometimes they will struggle and not to take it personally,” Tammy says. “It doesn’t end with time always. Sometimes it gets a little less intense, but it doesn’t end.”

Had this happened early in their marriage, Tammy says she might not have stayed with him. The parents of three sons, they have made it 44 years now.

She does have boundaries, and lets him know when they’ve been crossed. She said it’s important for him to understand that even though he has PTSD. The symptoms are sneaky.

“You just never know when it’s going to hit. I’ve gotten to know some of the triggers he’ll have and try to avoid those or help him avoid those. But it doesn’t always work,” she said.

They don’t make lasagna anymore.

Morgan’s triggers include his wife using a curling iron. He can’t take the smell of burning hair. Airplanes flying overhead are another trigger. His home sits on the glide path to the Salt Lake airport.

“Every time I watch those planes coming, I know I’ll have a visit from the demons that night,” he says, making the sound of a passing aircraft.

Morgan has no sense of value for things. He once called Tammy, a banker, to see if there was enough money for him to get a haircut. “Sure.” And then he called to see if there was enough money to buy a truck. “I’ll get back to you.”

At the same time, he finds it hard to pass up a bargain. He got excited about a 2-for-1 coffee ad. He doesn’t drink coffee. He discovered the Deseret Industries thrift store. He bought a pile of neckties because they cost a dollar. He has a half-dozen old golf clubs hanging in his garage that he paid $3 dollars each for. One of them has a wooden shaft. He’s looking for more with wooden shafts.

Morgan needs 2,000 rounds for each caliber of gun he owns. He doesn’t have that much, but that’s what he thinks he needs.

“Never know, those zombies could come,” he says.

Morgan does maintain a quirky sense of humor. Tammy says he likes to be funny — or likes to think he’s funny.

He has a few hobbies, including hot rods and drums. His neighbor gave him a rebuilt 1930 Ford coupe on the pay-me-when-you can plan. He bangs on his drum set in an upstairs room when he feels the urge.

He inexplicably started collecting rocks from Utah’s canyons and deserts. They sit in small piles on shelves around the house and garage. The workbench in his garage is cluttered with tools and cleansers and rags. His OCD made a U-turn.

Morgan’s psychiatrist put him on medications. The drugs prevent wild mood swings, keep him from blowing a gasket or spiraling too far downward. He hovers just under level. The problem, he says, is that he doesn’t feel happy or sad, love or hate. But the meds — “more than Elvis and Michael Jackson combined” — keep him alive. He still sees a psychiatrist every couple of months.

“If it wasn’t for psych docs and good old American pharmacology,” Morgan says, his voice trailing off. “There were times when I wanted to eat a gun but I didn’t.”

Tammy says she thinks about what life would be like had her husband not gone to Washington “all the time.” Morgan, though, doesn’t share that sentiment.

“I wish it never had happened, but I never regret going,” he said. Trips to the nation’s capital were part of his job. It’s where he learned how to do it better.

Morgan gets depressed when he thinks about young soldiers going off to war. That’s real sacrifice. He wonders why it wasn’t him.

“It’s not so much me that was injured. Part of what makes me sad emotionally is sending away those young soldiers, soldiers that I enlisted, I recruited, trained, and they don’t come back or they come back busted up,” he said.

“I served 34 years, five months, eight days, six hours. Some of these kids getting killed haven’t been in two years yet. They have their entire lives before them. How come they’re the ones that had to sacrifice? I’ve already used up all my life. Why them and not me?”

He knows it can’t be him now, but that is how his out-of-balance mind works.

Morgan also laments what he sees as a lack of passion for freedom today.

“I’m concerned about the attitude and complacency of our people,” he said. “If freedom isn’t sacred or even just special to everyone, it will never work.”

Morgan said his “psych docs” told him he goes on his frequent trips to avoid a circumstance or run from a memory. He can’t say how many times he’s woken up in the morning wondering what to do. Often the answer was to jump on the Harley and ride. He didn’t know where he was going. Didn’t care.

Tammy says she doesn’t worry about him. They stay in close contact while he’s on the road. “I think this is definitely a way that he copes, so why would I want to put a halt to that?” she said.

Two years ago, a van swerved into his motorcycle in downtown Salt Lake City, severely injuring him. His three sons took away his Harley and replaced it with a Mercedes SLK 300 convertible. It’s not quite the same as the hog, but not a bad trade. It’s turbocharged four-cylinder engine goes zero to 60 in 5.8 seconds. Morgan can’t hold up a Harley with his bad right shoulder anyway.

After spending an afternoon with a reporter and photographer, Morgan puts his shirts in the trunk, sets his bag on the grass next to the car and takes a seat on his front porch.

He’ll drive to Oregon the next day.