SALT LAKE CITY — He just couldn’t drag himself out of bed, though his wife and daughters were dressed and ready for another day at the “Happiest Place on Earth.” The Tylenol and ibuprofen they’d taken for scratchy throats the night before didn’t seem to be helping him at all.

So Justin Christensen declared he’d just stay put. Then the 42-year-old, who normally doesn’t slow down, pulled the covers up past his beard and mustache and went back to sleep.

He and Rayna had been planning this trip to Disneyland for months. They wanted to take their four kids on their first real vacation before their oldest daughter left for college.

The clan was in high spirits when they left Grantsville on Sunday, March 8, stopping for a night in Las Vegas en route to Anaheim, California. They were traveling with friends who own a timeshare and had gotten them Disney passes, which put the trip within reach on a tight budget.

Tuesday was perfect. Wednesday, they did it again. On Thursday, Justin hit a wall. He was just too tired to get up. Had they walked too much? Or gotten too much sun? One of their friends wasn’t feeling well, either. Even their sons wanted to lounge in the condominium. So Rayna, 39, and the gals hit the park alone.

By Friday, Justin was clearly sick. Rayna wasn’t feeling great, either. They cut the trip short. None of them dreamed that the drive back to Utah would be part of a much longer journey to the heart of a global pandemic — with no guarantees that everyone would make it home.

A pandemic unfolds

On March 11, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. The respiratory infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus was spreading across the world, hammering Italy, Iran and South Korea. But the brunt had not yet fallen on the United States, and Utah seemed almost exempt.

Details of the disease were largely speculative, beyond shortness of breath, fatigue, fever and dry cough. The WHO warned of dire outcomes for the elderly, people with chronic medical conditions like diabetes and anyone immune-compromised. Hospitals and public health officials planned for a surge of patients. Many politicians, including President Donald Trump, downplayed the virus.

Three months later, COVID-19 has killed more than 423,000 people, including about 114,000 in the U.S. — nearly the population of West Jordan. More than 2 million cases have been identified in the U.S., including at least 13,500 in Utah, where 139 have died, mostly older adults.

Most people experience mild symptoms, if any. There are peculiar symptoms like loss of taste and smell or “silent hypoxia,” where patients lack oxygen but don’t feel short of breath. But the virus can also be devastating. Some say they cannot breathe, like a “dry drowning.” Some have gastric distress. Some develop bacterial pneumonia or kidney or liver problems. Blood clots, heart attacks and strokes afflict patients as young as their 30s. Young children may have rash, red eyes, and swollen hands, feet and glands.

Doctors are still figuring out to how to treat the disease, which has no proven cure. The challenge is great because COVID-19 attacks patients differently; care varies even from room to room in the same hospital. It’s still largely a matter of managing each complication that arises.

As the Christensens were about to find out, COVID-19 can change quickly from a distant news story to a battle for survival.

A shocking turn

Three days later, Rayna pulled the black Cadillac Escalade as close as she could to the door of Mountain West Medical Center in Tooele. The afternoon was warm for March, 58 degrees, but Justin felt chilled. Only patients were allowed inside, so he handed Rayna his wallet and patted his pocket to make sure he had his phone. “Call me when you know something,” she said. “I’ll come get you.” Then she watched his back disappear through the glass double doors.

She wasn’t worried, even though Justin had been pacing and panting that morning, in too much pain to take a breath. She figured he needed oxygen and maybe medicine. At the doctor’s, both were swabbed for a COVID-19 test. Justin’s blood oxygen level was just 65% — above 90% is normal — so the doctor sent him straight to the hospital. But Rayna didn’t know anybody tougher than her husband, an Iraq war veteran who drives a semitrailer for a living.

He was strong enough to be tender. They’d met at Snow College South in Richfield, two decades before. She was studying cosmetology. He was becoming a welder — one who needed a haircut. He charmed her as she snipped away. They eventually married and had four children: Keyera, 18, Kyle, 16, Kaycia, 14, and Kanyon, 10. Justin grew into a down-and-dirty dad who wrestles with his kids, but snuggles, too. Even in the tough times, he still made Rayna laugh.

So she dropped him off, picked up her own prescription — steroids for inflammation in the lungs — and went home to eat dinner with the kids and wait for his call.

A doctor called instead. Justin was on a ventilator. He’d crashed after being admitted with fever, chills and hypoxia. They were sending him by ambulance to the University of Utah Hospital in Salt Lake City.

Anxious, she called, but Justin wasn’t there yet. She went on Facebook and asked her friends and family to pray for him. All she could do then was wait and worry, as her own symptoms got worse.

Within hours, Rayna was back at the hospital, disappearing into those same doors. She tested positive for COVID-19. Two days later, she was well enough to go home.

She isolated in her bedroom for 14 days. The warm grays and whites weren’t as cozy without him.

Her days were punctuated by phone calls from the hospital. She’d brace herself on the edge of her bed, a notebook in reach on the fluffy gray fleece, and face a giant canvas print of a family photo hanging on the bedroom wall. Just last year, they’d all posed in front of an old truck, Justin at the center.

Rayna cried a lot during those calls. Nurses sometimes cried with her.

She was hungry for news, but hated to answer the phone. Bad news kept piling up.

She’d take a few minutes to digest it, to choose her words before telling the kids.

Once, the doctor’s voice was particularly grave. You’ll probably face very tough decisions soon, he told her. You’d better prepare.

Are you a father? she asked.

Yes, with four kids, he replied.

Like Justin, she thought. “Look at him as a man, as a husband, as a father, please, if you do anything to him,” she begged.

Trying to save him

Justin’s caregivers were already fighting with everything they had, but his lungs were filled with sludge and he just couldn’t breathe. They tried proning — flipping him on his stomach to take pressure off his lungs. They tried hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial long shot. But his oxygen level remained a dismal, dangerous 75%. He had hours, maybe a day, said Dr. Craig Selzman, a cardiothoracic surgeon who helped coordinate Justin’s care. So they opted for a more aggressive measure.

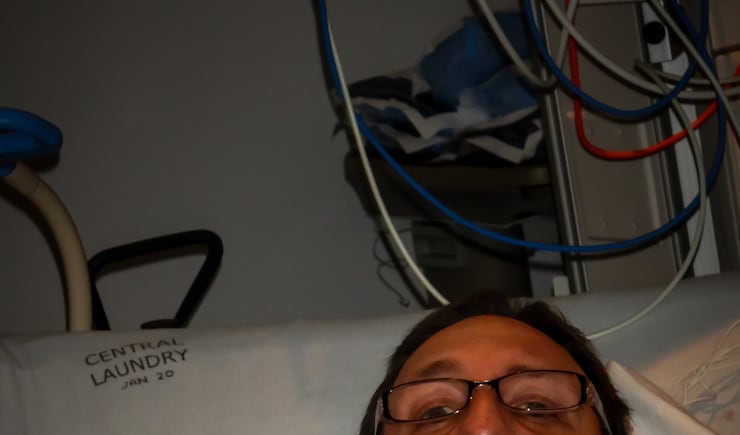

Six days in, Justin was put on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, which became for him a kind of artificial lung. On ECMO, two hoses the size of small garden hoses feed into a tube in the neck that goes straight to the patient’s heart. One hose draws the blood to an external machine that filters out carbon dioxide and adds oxygen, while the other puts it back into the heart, which pushes it to the rest of the body. The treatment is fraught with risk, but Justin’s situation was dire.

“I think if we had waited six hours, he’d have died,” said Kathleen Stoddard, the clinical nurse coordinator and operating room nurse who oversaw much of Justin’s care because she’s in charge of the ECMO program. She wasn’t even sure he’d survive the procedure to install ECMO. It’s typically used only for short periods because of risks and potential complications.

Cardiovascular intensive care unit nurses trained to manage ECMO volunteered to care for Justin in a separate ICU where COVID-19 patients were isolated. They had to don protective gear every time they entered the room, then take it off afterward. It was time-consuming, on top of a labor-intensive job. Normally, one ICU nurse manages two patients. ECMO, Stoddard said, requires two nurses per patient. One stayed in the room with Justin the entire shift, managing and monitoring the machine.

The team gave Justin drugs to reduce inflammation and other drugs to calm the cytokine storm COVID-19 has made notorious, which was making his immune system attack not just the virus, but Justin’s own body. They enrolled him in a clinical trial to see if amniotic fluid would reduce inflammation and promote healing. They gave him an experimental drug called remdesivir.

It still wasn’t enough.

A simple connection

Rayna and the kids watched on a screen as nurses gave them a virtual tour of Justin’s small room. His bed faced the glass door so the team could watch him and the numbers on his machines. A whiteboard listed notes Rayna had sent about the kind of person Justin was so they would know who they were treating. In the bed, his neck was so swollen it swallowed his sharp jawline.

The phone calls had been replaced when the hospital got iPads to bridge the distance since family couldn’t visit. The nurses attached an iPad to his bedside table and often left the connection open so Justin could hear the sounds of his home life: meals and conversations and the kids trying to keep up with schoolwork. Nurses sometimes played his favorite music on Spotify.

At the Christensen house, the laptop would stay open on the kitchen table. The family watched him sleep. They talked to him in spurts, telling him he was a good dad, a wonderful husband, a source of joy, as the ventilator made puffy breath sounds in the background. Kyle reminded him he’d promised to teach him to fix cars. Keyera told him about a guy she was dating. Rayna said “I love you” over and over.

They wondered if their words were their goodbyes.

Each morning, for a few precious moments as she woke, Rayna would forget Justin was 45 minutes away, kept alive by machines. Then reality would smash her and she’d ask God to love her family through whatever was coming. She prayed the doctors would know how to save him and have the resources they needed to do it. Then she’d dress quickly because she’d been promised that despite the visitor ban, if he got worse and there was time, they’d let her — only her — tell him goodbye.

She didn’t want to squander seconds getting ready.

The kids were struggling with their own fears, but tried to make things easier for Rayna. Keyera would try to encourage her, while Kyle tried to be strong. Kaycia usually teared up. It was Kanyon who voiced their mutual dread, sometimes begging Rayna not to tell him any more. Other times he’d ask, “Is dad ever coming home?”

Justin seemed to be shrinking as Rayna watched. He spent their 19th anniversary in a sedation-induced sleep.

Politicizing pain

A stranger’s anger squeezed the air from Rayna’s chest. Her life had moved further online as she connected with friends, family and occasionally strangers on social media, as the pandemic shutdown and her husband’s condition carried on. But this message berated her for “spreading the COVID lie.” He asked if she was being paid. She didn’t know who he was or how he knew her husband was sick.

His wasn’t the only nasty message. A woman she’d considered a friend said Rayna was killing her husband by leaving him in the hospital.

The fight for Justin’s survival had become fodder for political debate, as America grew apart on questions like whether to wear masks or how soon to reopen certain businesses or whether the disease was a hoax, one party’s conspiracy against the other. Much of it played out on social media.

Rayna decided that people hiding behind keyboards were often cruel — especially anonymously. “People used to write in their journals — and had a fit if someone read those private thoughts. Now a lot of it’s spewed on Facebook and people get mad if you don’t read it,” she said.

But she found kindness online, too.

A couple diagnosed with COVID after taking a cruise reached out to her after someone shared Justin’s story. Friends and strangers offered support and comfort. One woman assured her Justin could come off ECMO; her husband had.

That kind of support and her own faith held Rayna together. She asked doctors to pray for themselves and for Justin before any procedure. Many promised they would. Members of the Christensens’ ward in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints offered prayers and food and more. She later learned that a family friend who worked at the hospital gave Justin bedside blessings. “He showed up when we needed that,” she said, another sign of God’s love.

Like Rip Van Winkle

To reduce the number of tubes in his so-swollen neck, doctors changed his ventilator, attaching it through a tracheostomy. Then they could start reducing the sedation that had kept him from pulling out the tubes. As he started coming around, Justin didn’t know where he was; he’d gone to bed in Tooele and woke up in a nearby town. Like Rip Van Winkle, he’d been asleep far longer than he thought. As Rayna watched, Justin held an erasable marker to a whiteboard and for the first time in many weeks, he spoke his mind. “I love you, Rayna,” he wrote, the printing shaky. “How are the kids?”

It was a shred of hope, shaky though it was.

Justin had had complications along the way, developing bacterial pneumonia, which isn’t uncommon with ravaged lungs. He had already “been beaten to hell by COVID,” as Selzman saw it, “then he got a super-infection on top of it.”

Complications are one reason COVID-19 has been such a puzzle for clinicians, although they’re used to caring for really sick people, Selzman said. “We’re always playing zone defense.” They treat edema, inflammation, bleeding, nausea, breathing trouble — and tackled Justin’s care that way. Still, “his lungs were as bad as they get,” Selzman said.

ECMO had served as artificial lungs; without it he could not breathe, but he remained on the ventilator, too. Doctors couldn’t predict how much scarring COVID-19 had created or the long-term effects.

Even so, Justin was lucky. He never needed dialysis. His liver kept plugging along. His heart required medicine, but didn’t fail. He was young and healthy before the coronavirus. He didn’t smoke or abuse alcohol or have underlying disease. And Utah had not been overrun with SARS-CoV-2 infections, so the equipment shortages that plagued hot spots like New York — where patients had to share ventilators — did not materialize in Salt Lake City.

Rather than an overextended staff, Justin had attentive care from more than two dozen nurses. Add in doctors, physical and other therapists, chaplains, housekeepers, respiratory care experts, radiologists and lab techs, among others, and easily 100 staffers were part of Justin’s care, said Dr. Nathan Hatton, the pulmonary/critical care physician who was Justin’s primary doctor at the U. He thinks they all probably thought Justin was going to die.

Instead, he improved, incrementally at first, moving around in the bed. He was terribly lonely. He felt confined. He couldn’t leave his room, even to walk, for fear of spreading the virus, so his caregivers moved furniture to give him room to pace.

In a nine-second video of one walk, a nurse can be heard telling him to do the “Beauty Queen Wave,” then “wipe a tear, wipe a tear and blow a kiss.” With wife and children watching, Justin complied, playing it up for his “subjects.” He worked hard. Soon, he didn’t need a walker. Days later, still hooked to the ventilator, he did squats, Stoddard said.

On May 3, doctors took him off ECMO. On May 9, doctors put in an even smaller tracheostomy to see how Justin would do, then removed the ventilator entirely the next day. The hole in his neck would heal. Finally, he could eat and drink.

Homecoming

Two days later, Rayna got up early and dressed for a trip to the hospital with the kids. She’s still recovering from her own case of COVID-19, still fatigued. She’s been a stay-at-home mom and must find a job and figure how to balance that with the care that Justin still needs. He won’t be driving a truck for who knows how long. The medical bills haven’t arrived yet, but this was a miracle. Before leaving their driveway, the kids wrote “Thank you U of U for saving our Dad!” on the Escalade windows.

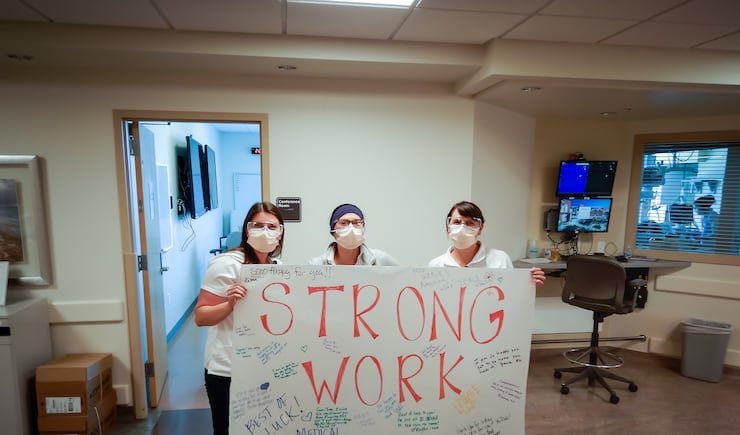

Inside the hospital, staffers were penning messages of their own. One wheeled Justin past dozens more who lined the hallways holding a poster and cheering him on. He emerged from the hospital like a traveler leaving the airport, but with the cannula in his nose and an oxygen tank.

He’d lost 40 pounds.

At home, Rayna wanders to the window to watch as Justin, still weak, goes outside, trailing 100 feet of oxygen hose behind him, stepping gingerly down five steps and onto the lawn, where he lies down to watch clouds float across a blue sky.