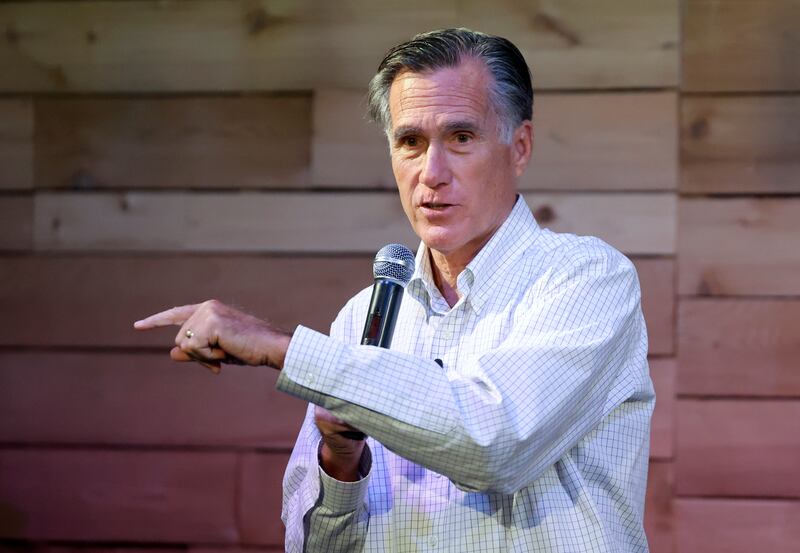

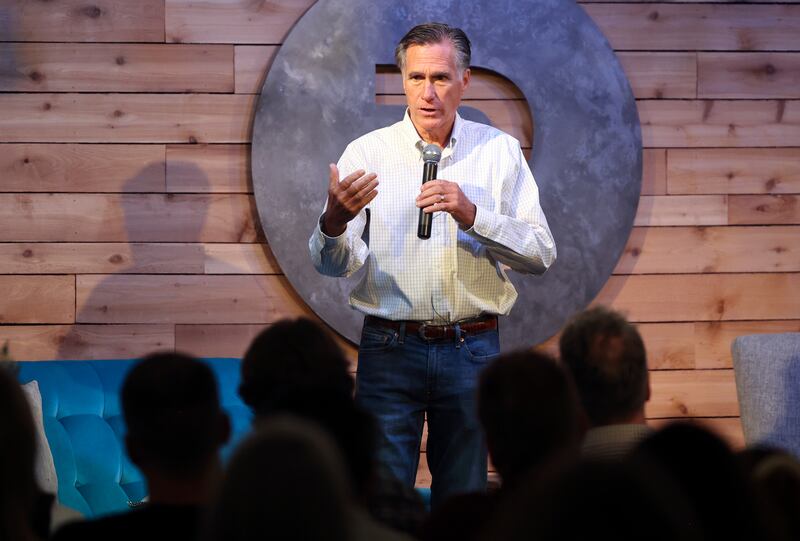

Perhaps it’s because he was a governor before he was a senator, but Sen. Mitt Romney looks as comfortable climbing down a steep embankment to stand under a bridge in an upscale Sandy neighborhood as he does being interviewed by a group of appreciative entrepreneurs at a Provo business.

He’s been doing this a while.

When he was in the state this past week, stopping to check in on projects related to the bipartisan infrastructure bill and meeting with residents, he climbed under the bridge with a Department of Transportation inspector beside him, to understand how federal money would help save it.

He continues to be asked if he will run for reelection or if his time in public service, at age 76, is coming to a close. And he responds that he will make the decision based on whether he has unfinished business. So when I sat down with Utah’s junior senator recently in a conference room at RevRoad in Provo, Utah, I asked, what is your unfinished business?

He was ready for the question.

He lists four things he sees as the biggest problems facing the country: the nation’s debt and reforming entitlements like Social Security and Medicare, two things that go hand-in-hand for Romney; developing a strategy to address China’s growing power in the world; climate change; and, helping improve the nation’s social capital, or the ties that bind us together in families and as a society.

“So you’re looking at what things can you do as a senator, and what things can only be done as a president — I’m not going to run for president again, even though I wish I had that job — and so I’m getting an assessment of whether we can make progress on those fronts,” he said.

These are the federal issues he’s focused on. At the state level, he says he wants better use of public lands. He accused Democratic leaders, like President Barack Obama, of playing politics with the issue by protecting some land that should be protected, but also some that shouldn’t.

This is another theme for Romney, who has styled himself as a doer in Congress. In the land of workhorses and show ponies, he wants to be a workhorse. But the problem is, while there has always been an incentive to preen for the public, the advent of first cable news and then social media seems to have made that problem worse.

And what do you do when both the left and the right are winning with their bases on an issue, but possibly hurting the country in the process? How do you get things done?

Romney on Tuberville, military promotions and the Pentagon’s abortion policy

He pointed this out when we spoke about Alabama Republican Sen. Tommy Tuberville, who has for months held up military advancements because of a Pentagon policy change on abortion. There is a law that says the Pentagon cannot pay for abortions, but after Roe v. Wade was overturned, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin implemented a policy of paying for pregnant service members to travel to states where abortions are readily available if they live in states where they are not.

Tuberville and other pro-life Republican senators, including Sen. Mike Lee, saw the policy shift as a dishonest sleight of hand, a way to get around the law on payments for abortion. So Tuberville vowed to hold up military promotions until the policy is reversed, and he has, for months.

But look at the incentives — “this conflict is working for the Democrats and it’s working for Sen. Tuberville,” said Romney.

He expressed discomfort with using “the extraordinary powers of a senator to impose a moral point of view on the entire body,” but also pointed to the Biden administration’s decision to put in place a policy, through “unilateral action which is offending the morals of half the country.”

“This is not the way it should work,” he said.

But what incentive does either party have to negotiate or back down?

The credit rating downgrade an ‘enormous deal’

On the issue of the nation’s debt and a recent credit downgrade — which will make taking on new debt more expensive, and could worsen the deficit — Romney expressed similar frustration.

Lawmakers want to get reelected, he said, and so they won’t tackle the biggest problem in the federal budget: entitlements.

“It’s an enormous deal,” he said of the downgrade. “And what we will do is we will focus on expenditures that represent less than 1/1000 of 1% of federal spending, and we will scream and holler about waste and about some crazy expenditure, and maybe even shut down government to show that we’re fighting to create balance, but we won’t even touch or even discuss two-thirds of our spending, where all the growth and the excesses are, because we know that if we do that it might hurt our reelection chances.”

When I ask whether that’s a valid concern, and if they should do more to talk to voters to convince them of the need for reform, he shakes the question off.

Ultimately, Romney says, the people elected to solve these problems must come together to fix them — “people on both sides of the aisle that are willing to put the right policy ahead of the right politics.”

There are people like that, he says, including the group of 10 senators he worked with on the bipartisan infrastructure bill. But he worries because of fears around any change to entitlements, the issue might be too much even for this group.

“We’re not going to touch this until it’s a crisis. The problem is, when it becomes a crisis, the action that has to be taken becomes pretty draconian, very painful. If you can avoid the crisis from occurring, the adjustments are modest. But if you wait until you’ve gone off the cliff, as you see, for instance, with Greece and Italy a couple of years ago, when they got into debt trouble, it’s really painful to get out of it — and if the largest economy in the world, ours, gets in trouble, why, the world is going to suffer and we will suffer.”

“So, the downgrade, it’s an indication of what’s going to come.”

Where does this leave Romney?

He says he hasn’t made up his mind on whether he’ll run again or not, but he is insistent that he’ll only run if he thinks he can make a difference.

His decision may hinge on how the presidential race shapes up this fall, and whether some of his close allies — members of the group of 10, like Sen. Joe Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia, and independent Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona — decide whether they will run for reelection.

If his remarks to a room full of entrepreneurs at RevRoad was any indication, he still has a fire in his belly for policy, for the state of the nation and the world.

But whether he still has enough fire to be willing to slog through the partisan politics in Washington, D.C., is another question entirely.