Editor’s note: Deseret News reporter Amy Donaldson and photojournalist Spenser Heaps traveled to Puerto Rico last week to chronicle the efforts of Utahns trying to bring relief and comfort to those suffering in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. This is the first in a series of reports.

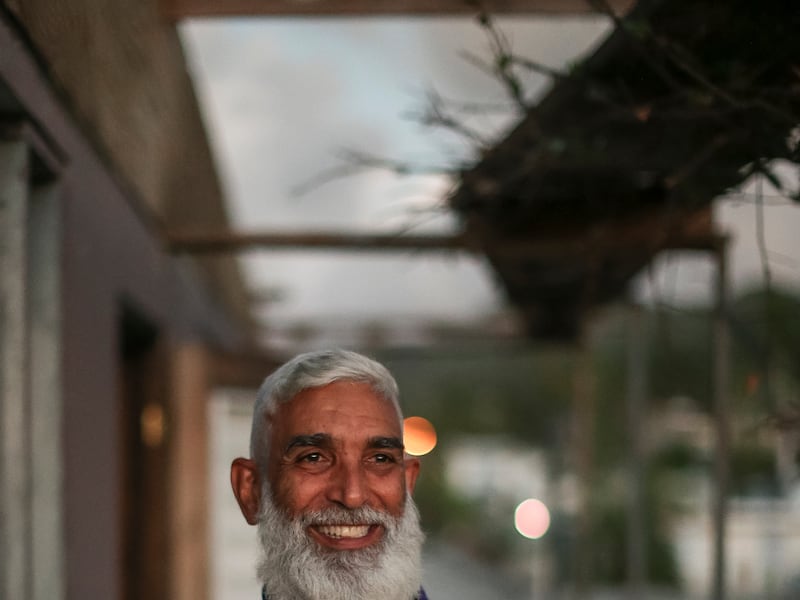

LAS MARIAS, Puerto Rico – Luis Barreto saw the orange buckets strapped to the roof of a slow-moving minivan and cried out for help.

Northern Utah businessman Ben Davis had slowed the rented van crammed with relief supplies and volunteers from Utah as he considered if the GPS was leading them astray, once again, as they navigated the narrow, mountain roads of Las Marias, a rural community about 80 miles west of San Juan.

The 44-year old father of three eased the minivan next to the curb in front of Barreto’s house where he stood with his wife, 24-year-old daughter, and two neighbors. Instead of pleasantries, Davis and Barreto open with an exchange about whether or not Barreto’s home has power and water.

“We were 67 days without water,” Barreto tells Davis, as his 16-year-old son Statton and his Providence , Utah neighbors, Al and Dan Dustin, climb out of the van and start pulling out solar lights and water filters. They aren’t government aid workers, like Barreto suspected, but instead are just with a group of volunteers from Utah hoping to help some of the thousands of families who remain without power and water nearly three months after Hurricane Maria decimated the Caribbean island on Sept. 20.

“We still don’t have power,” Barreto said. “The town had power two weeks after the storm, but we got nothing.”

When the local men gathered around Barreto, all sprinkled with sawdust from efforts to repair a nearby home, saw how Statton converted the orange bucket to a water filtration system and how they could light a room or charge a phone with the Goal Zero hand-held solar light, the atmosphere erupted into something of a pre-holiday party.

Hurricane Maria changed the landscape of Puerto Rico, but it also reshaped nearly every aspect of daily life for the more than 3.4 million Americans that live in the U.S. Territory. The airport is busy. A mall nearby the airport is humming and bustling with power, activity, and air conditioning. But just miles away, down broken roads, isolation and darkness remain.

“Life has changed a lot,” Barreto said. “My grandfather and great-grandfathers, now I know what they went through,” he says. “They had no power, no water. We do what we can to get water and ice, but light, well, we just got used to the dark. We go to sleep like the chickens. Six or 7 o’clock we’re already in bed.”

His description of their sleeping habits elicits an explosion of laughter, which is a welcome reprieve for his neighbors who are a tenuous mix of gratitude and frustration.

“Everybody helps each other,” said Barreto, who was born and raised in Boston, but moved to Puerto Rico 20 years ago. “If I need something or they need something, we try to work together, you know. But it’s been hard. It gets harder every day.”

His Boston accent cracks as he admits they feel forgotten by both the rest of America and their own government.

“Pretty much,” he said, sobs choking him into silence. “Not because of me, but because of my daughter. We’ll go on like this if we need to. But she’s stopped studying. She’s not going to school. It’s hard.”

Before Maria dismantled their lives, he watched as the U.S. rallied to help those victims of Harvey in Houston and Irma in Florida. His frustrations are less political statement and more simple observation.

“I just can’t understand why Miami and Texas, in less than two or three weeks, they got light,” he said. “I understand a lot of the people that are working the electricity here in Puerto Rico, they’re not doing their job. …But we’ve got to get help from the United States to put this country back in its place.”

On this December weekend help has come from Utah, with 40 volunteers who joined forces with Light Up Puerto Rico to bring not just light, but hope to those in need. It is a group of former Mormon missionaries and Puerto Ricans living in Utah who organized a fundraising drive in the wake of the storm.

Light Up Puerto Rico is led by Jorge Alvarado, a native of Puerto Rico, who also served as an LDS Church mission president in Puerto Rico from 2010-2013, but now lives in South Jordan. This is his third trip and he plans to return every month, armed with solar power and those orange buckets, as well as, tarps, fans and roofing material. While Alvarado leads the effort to install solar-powered generators to the most desperate and fragile, the group of about 40 volunteers organized by Davis and his Lendio colleague Mark Santiago rely on inspiration.

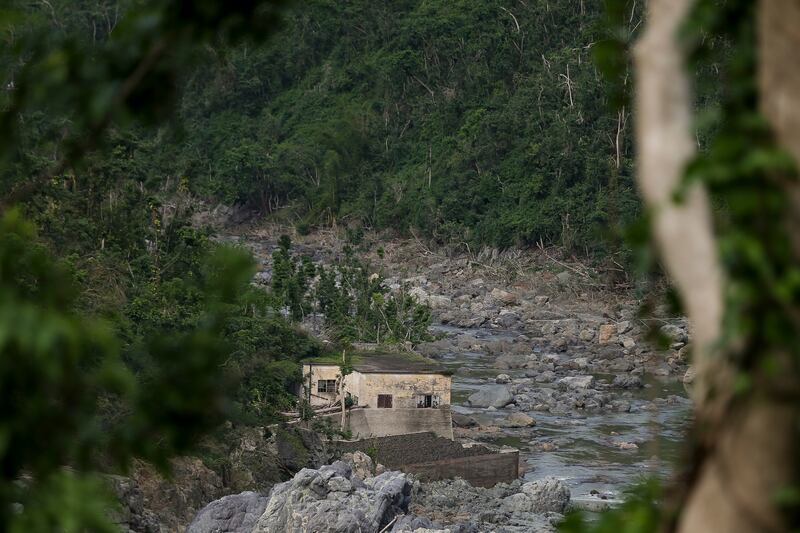

Alvarado uses referrals to deliver solar panels and generators, while Santiago and Davis and their group simply load up their rented vans with supplies and drive to areas locals suggest, often finding mountain roads still littered with downed power lines and debris, as well as dead-end streets created by ruined roads or mudslides.

That brought led them to Jose Ortiz last Saturday, a man loading food for his uncle into his car. Al Dustin suggested they stop and ask if they needed help as their house was missing some windows and a front door.

When Davis asked if they had clean water, Ortiz was skeptical, almost rude. He’d seen and heard how some people prey on the desperate circumstances of others to make a little extra money.

“Later he apologized profusely,” Davis said, “saying that there was no way he could have anticipated the first aid workers he’d see since the hurricane would be a van full of white dudes.”

He sent his own 16-year-old son, Tony, to bring his neighbor, July Rodriguez, to talk with the men as only Davis spoke Spanish.

The former LDS missionary learned Spanish while serving a mission in New York City from 1993-1995. More than half of the people Davis worked with during that time were Puerto Rican. His affection for them transcended decades and distance, so when Santiago, who not only served a mission in Puerto Rico but also played professional basketball for the Arecibo Captains, suggested they organize a relief trip to the island, Davis embraced the opportunity.

“Mark and I worked really hard to make sure we spent a lot of time on Facebook and talking to as many people as we could find, to make sure we had the right stuff, things they actually needed,” Davis said.

“Like the USB fans. In a million years, it would never have occurred to us to bring the USB fans, but we talked to several people who were telling us about the elderly, that the death count is probably closer to 2,000 or 2,500 or so from the storm because of all these elderly people who’ve passed away because they just can’t sleep at night. It’s too hot.”

The official death toll stands at 62, but an analysis of mortality data by the New York Times suggests more than 1,000 died on the island in the storm and the weeks that followed. Locals believe it is even higher than that.

This was Santiago’s second relief trip. He traveled to Puerto Rico in October with his brothers as part of Light Up Puerto Rico.

“After that, we were thinking, ‘How do we follow that up?’” Santiago said. “We can’t just come down here one time. That’s just a drop in the bucket.”

Santiago suggested they make the trip a father and son endeavor, and the group quickly grew to more than 40 people.

This time they coordinated their personal efforts with Light Up Puerto Rico, which is working with dozens of businesses, many Utah companies, and committed to bring humanitarian aid to Puerto Rico for as long as the recovery lasts.

While the groups of fathers and sons drove the countryside in minivans and pickups crammed with tarps, fans, hand-held solar lights, candy, toys and dozens of humanitarian kits donated by local youth groups and churches, Alvarado and Utah businessman Brad Creer crisscrossed the island, in part to avoid road closures due to landslides or construction, setting up generators powered by solar panels for the most desperate and fragile.

Victor’s story

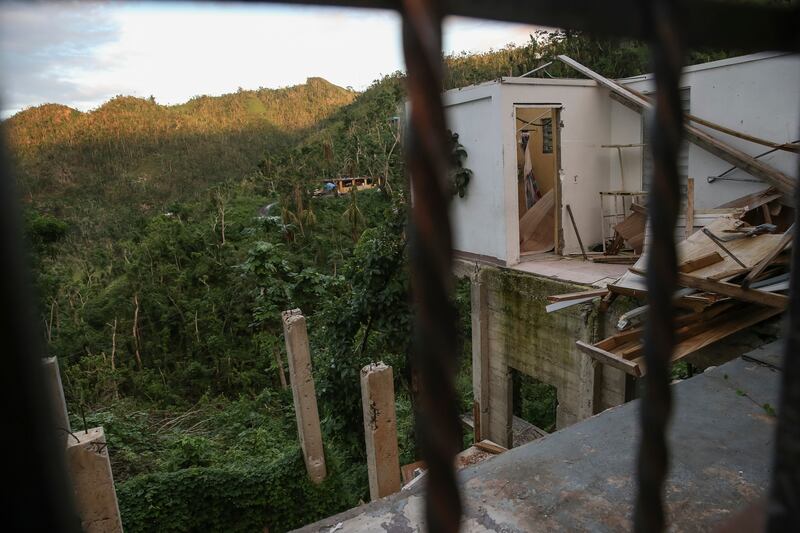

Victor Felix was showering at a neighbor’s house when Alvarado and Creer showed up to set up his generator because the house he shares with his 80-year-old mother is without power, water and a roof.

When he emerged to greet Alvarado and Creer, the 61-year-was wearing a purple Weber State shirt, telling stories of his old friend head football coach Jay Hill, who served an LDS mission near Felix’s home.

Felix doesn’t miss any of the material possessions he lost when Hurricane Maria ripped the roof from the two-story home that, for 18 years, was also home to LDS missionaries for whom he loved to cook while discussing religious doctrine. But it seems he has traded possessions for worry.

“The water came inside my mother’s home,” he said, as he led visitors through the damp, mostly empty rooms describing the kinds of living that used to take place in the shell that now stores only the most sentimental but severely damaged belongings.

“It was awful. I just kept putting blankets and Pampers in the door, moving my mother and putting buckets for all the dripping so she wouldn’t get wet. I worried about my mom, but I had my faith for so long … I always trust God in my heart.”

He chokes up when he points at the pictures damaged by water, and his library has been reduced to two dozen mold-covered selections.

His mother, Mariana, is bedridden and threatened by sweltering heat during the day. Food and medicine needs to be stored in a refrigerator, but without power needs can only be filled on a daily basis. Solar-powered panels now mean refrigeration, fans, light and the chance to watch her favorite soap opera.

“I feel weak many times,” he said, fighting tears. “My mother takes everything out of me. I don’t have the strength. I rely on my neighbors for changing her diapers. …It’s been hard, but I see people who’ve lost everything. So I say, ‘Thank you, Lord. I’m still here.’”

Santiago and Davis decided to begin work nearly two hours from San Juan in Comerio, a mountain community where baseball fields have been turned into dumps, and then stayed in Rincon, a resort town that boasts some of the most famous surfing beaches in the world.

Communities with power and water bustling with all the signs of normalcy stand in stark contrast to those areas where residents can barely remember what normal looks like.

“I’m still surprised,” Santiago said of the number of people living without power or water. “I step back and say, ‘Wow, it’s been 90 days.’ If this were to happen in the states, there would be rioting in the streets. So I’m still surprised. And I think the numbers that published in terms of who has power are very misleading. And the people know that here. If you have a generator, they count that as power. And that doesn’t really count.”

It doesn’t count because, as one man told Alvarado after he and his crew capped an hour-long search for a restroom after dark with a visit to a Burger King, it costs him about $200 every four days to power a generator only at night.

Irma Picket

Generators are an expensive, noisy bandage on a mortal wound. It is how 70-year-old Irma Picket has kept her bakery running during daylight hours these past months.

“We haven’t had power for three months,” said Picket, acknowledging the bread is made possible by a generator that powers her gas oven at home. “I have to close here about 5:30 in the afternoon because it’s too dark. …I have had no help at all.”

She rattles off a list of places she’s gone and officials she’s begged for help in her effort to restore power to her hilltop bakery and small store near Rincon, a picturesque beach town.

“Yesterday I went to the electric company,” she said as volunteers from Utah buy loaves of bread and leave her with solar lights to charge her phone. “The only thing I saw on the paper was ‘Rush’ written on it. That’s it. This is too much for a small business.”

Working alongside her elderly brother, she has to bring water from home just so they can use a toilet while they work. She knows many people who’ve left Puerto Rico for the mainland, as an estimated 100,000 people have done, and she admits she’s contemplated doing the same. Her daughter lives in Puerto Rico, but her son lives in Portland, Oregon.

“Sometimes I am so tired,” she said, acknowledging that she has to make long, expensive runs to restock her shelves. “I just say, ‘That’s it.’ Especially when this (generator) goes out, and I have to look for a technician. But I have to be here. This is the only place in the area.”

She looks up at some of her neighbors as they collect a few food items that won’t spoil as they are still without refrigerators, and acknowledges that her tiny bakery is something of a lifeline for people in this small town.

“I have to do it,” she said, pausing, “for them.”

Juanita Arroyo Rivera

Sixty miles southeast of Picket’s Snow Bakery, traffic is halted while crews install new cement power poles in a neighborhood near the city of Ponce. Juanita Arroyo Rivera, whose days have been marked by anger, frustration and fear these past months, watches with her autistic son as crews work.

Speaking through a translator, she laments the rush by officials to get power restored to restaurants, hotels and the famous shopping mall - Plazas de Americas in San Juan – while hospitals languished in the dark without clean water.

“There were people who died,” she said. “The government has not spoken about this. People who were in the intensive care, the babies in NICU, that were intensive, they died. I have friends who are nurses, who used to work in those hospitals, and they told me the smell that was coming from the people who were dead, the people in the morgue, it was overwhelming. The government has not revealed the truth about what happened in those hospitals.”

Like Picket, the 60-year-old has a long list of officials she’s sparred with over restoring power to her community. She finally went to her neighbors and took up a collection. They paid $80 each to buy five power poles and then paid extra to have them installed.

Alvarado is moved to tears repeatedly as he translates for Arroyo, reaching out and putting his hand on her shoulder as she talks.

As outrageous as her assertions sound, Alvarado believes they’re true. In his three trips, and through his family living in Ponce, he’s heard from people who buried bodies of loved ones in the backyard because they couldn’t get medical professionals to pick them up and take them to a morgue.

Like many Puerto Ricans, he has had an epiphany about the desperate circumstances that were somehow easier to overlook before Maria.

“I never realized how poor we were,” Alvarado said, as he sat down to a roadside dinner with volunteers featuring all of the holiday favorites. “We lived in poverty. All around this Island there were curtains of prosperity, and Maria ripped them away. There are a lot of people…”

He puts his head down and sobs, while locals revel at a nearby outdoor bar. He calls the hurricane “the greatest robber of them all.”

July Rodriquez

July Rodriguez didn’t think there was much that could unravel him. He was born and raised in the Bronx, hardened by six years in the Air Force collecting the remains of fallen soldiers, and infused with patience that comes from decades of growing produce in Puerto Rico.

But the devastation and isolation imposed on him since Hurricane Maria slammed the small Caribbean Island almost did.

“This one was the worst,” the 65-year-old retired postal worker said, pausing. “After the hurricane passed, and I saw what it had done, I didn’t sleep for maybe a week. It was depression, anxiety. I didn’t know what I was going to do, how I was going to live. …It was too much.”

A couple of days after the hurricane, his closest neighbor, Jose Ortiz asked him to help him clear the nearly two miles of steep, windy road from their sparsely furnished, cement houses to the nearest town.

“It felt heavy,” he said of considering a move from the U.S. territory to the mainland. “It felt like running away from something, and I’m not one to run away. That’s not what I’m about. So when he said he needed help, I said let’s do it. He was losing it too. …We got the chain saw and just started cutting. And soon it started clearing, and that gave us hope.”

On this sweltering Sunday morning help comes in a minivan full of Mormons – the volunteers from Utah. Sometimes they stop to offer help, while other times, desperate residents flag or chase them down.

Aida Valentine

Aida Valentine saw the minivan leaving Barreto’s house and followed it down a dead-end road the men mistakenly took. She asked if they were aid workers from the government, as she needed help covering her storm-ravaged tin roof. Davis tries to explain who they are and agrees to follow her to the house her mother has had to abandon because the roof leaks so badly.

As she shows them the roof, covered with old, tattered tarps pinned down with cinder blocks, she tells them that her father died a few days before Hurricane Maria hit. Officials took his body to a nearby morgue, but they told her after Maria decimated the island’s power grid that they had to dispose of the body as they had no way to store it until a funeral.

As she talks to them, Davis notices her knuckles are rubbed raw from washing clothes in a creek, and retrieves a first-aid kit and some gloves for her from the van.

“It has been really difficult to try and process the grief of the hurricane with the grief of losing my father, at the same time,” she said. “The hardest time for my mother is when she cooks. My father loved to eat. My mother loved to cook for him.”

After the hurricane, Aida hid the plate her father always used, hoping it would spare her mother even more agony.

“Just seeing it crushed her,” she said. “Our lives have changed a mountain.”

As Davis talks with Valentine, the other three men cover the roof with new, thicker tarps using roofing nails. It takes about 90 minutes, and Dan Dustin's legs are burned from kneeling on the scorching surface. Just as they finish, three men pull up next to the house to feed and water a horse, and they ask if the group is from FEMA. They saw government aid workers for the first time two days earlier they tell the group as they re-pack the dwindling supplies in the back of the van.

“I’m so glad they came,” Barreto said of the Utahans. “I’ve heard there is rice and beans that’s donated, but we’ve seen none of that.”

He understands the logistical issues associated with getting water and power to his rural community.

“We’re a small town,” he said of the community that numbers around 10,000. “It’s hard. You don’t know how to go around here, and you get lost. The roads are terrible. We lost a lot of roads.”

“It’s hard to get through,” he continues. “I mean, we didn’t get no gas for 47 days. That means the little bit of gas you have, you’ve got to save to go get water on a little mountain that spills water.”

He points to another man, and then details what it takes for him just to get to this spot, where on a Sunday morning, they found a relief in the form of some men from Utah.

“The bridge washed out by his house,” Barreto said. “It just disappeared. The road disappeared. It was horrible.”

The pitch of his voice rises and his tears fall. His neighbors stand in silence, and his wife chokes back her own tears.

“We’re still here,” he said. “We’re alive. We lost a lot, but we’ll go on, day by day. We’ll survive.”