LONDON — Experts on religious freedom convened for the third annual Notre Dame Religious Liberty Summit this week in London, and a well-known British politician was honored.

Lord David Alton of Liverpool, a member of the U.K.’s House of Lords, received the 2023 Notre Dame Prize for Religious Liberty. A crossbench, or independent, member of the House of Lords, Alton has spent four decades in Parliament. He is known for his stances on human rights and religious liberty.

“Lord Alton has had a long, distinguished career of fighting for religious freedom and against religious oppression all around the world — fearlessly,” G. Marcus Cole, dean of Notre Dame Law School, said. “He has dedicated his life to fighting oppression and made this noble cause the cornerstone for his work as a politician and public intellectual.”

Elected at age 28, Alton was the youngest member of the House of Commons. He is the founder of Jubilee Campaign, a human rights lobbying group, and Jubilee Action, a charitable organization. His pro-life advocacy eventually led to his leaving the Liberal Democrat Party, and he gained notoriety for authoring a bill that would have banned late-term abortions in the U.K.

“He’s just a towering giant,” the Rev. Dr. Andrew Teal, lecturer and chaplain at Pembroke College, said of Alton.

Past winners of the Notre Dame Prize for Religious Liberty include Nury Turkel and Mary Ann Glendon. Turkel is a commissioner of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom and an advocate of Uyghur rights. Glendon is a Harvard law professor and the former U.S. ambassador to the Holy See.

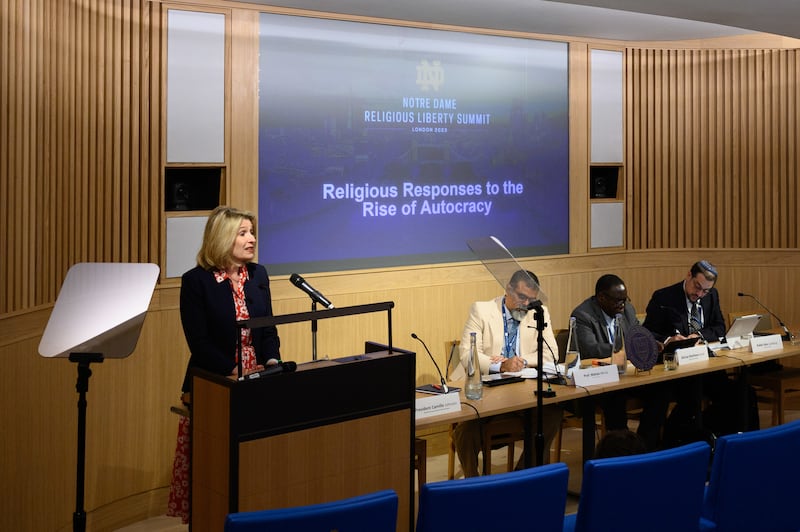

The three-day conference featured presentations from more than 60 scholars and experts representing numerous religious groups, academic institutions and nonprofits.

Emerging challenges

To open the conference, Notre Dame professor Stephanie Barclay introduced the theme: “Protecting Religious Liberty in a Rapidly Evolving Society.”

Barclay, director of the Notre Dame Law School Religious Liberty Initiative, noted that the summit would be geared toward providing many different approaches and frameworks of religious liberty, matching the evolving world in which people of faith reside. She noted that while some religious liberty issues are the same, there are new challenges, threats and contexts to consider, especially trends in social media and the corporate space.

Cole, the Notre Dame Law School dean, also welcomed attendees on Tuesday, encouraging them to center the conference on the people who are affected by infractions upon religious freedom. “What we need to do is focus, not on the politics, but on the people,” he said.

Cole noted that much of the success of the religious liberty movement will come from court decisions, but he expressed hesitance in celebrating these as victories on their own.

“We must recognize that while these victories are important, they will be fleeting unless we also begin to win in the court of public opinion,” he said. “We must explain the importance of religious freedom to all people, and as the basis of all of our freedoms, if we are to persuade others as to why religious freedom needs protection.”

Religious freedom in the U.S.

On Wednesday afternoon, a panel titled “Religious Liberty Legal Developments in the U.S.” explored court decisions that have affected freedom of religion, including the Supreme Court’s recent ruling on an evangelical Christian web designer who agreed to serve all customers, but refused to create a website that contravened her belief that marriage is between one man and one woman.

Over the past decade, the Supreme Court has delivered a near-perfect record in support of religious people or groups, said Mark Rienzi, president of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty and professor of law at The Catholic University of America.

Since 2012, of the 25 cases dealing with freedom of religion or belief, the court has moved to protect religious freedom 24 times, often in unanimous or near-unanimous decisions.

“We’re in the midst of a long, extraordinary run of religious liberty winning at the Supreme Court,” Rienzi said. And it isn’t just conservative Christians who have won cases: “If you look at the list of winners, it’s Christians and Muslims and Buddhists and Jews,” he said.

After the Supreme Court agreed to hear 303 Creative v. Elenis, the website designer case, some questioned how the case was different than the court’s 2018 ruling in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission. Rienzi explained that the court’s decision hinged on expression — it could be argued that baking and decorating a cake is not a form of individual expression, while creating a written website is — and the door was opened for the court to take up a case that, on surface level, looked very familiar.

“Whatever you wondered about a cake or a floral arrangement, you can’t wonder about a website,” Rienzi said. “That’s words. That’s messages. … It might as well be The New York Times.”

To Rienzi, the case boiled down to a debate over free speech. The court cannot mandate that someone must express themselves in one way, or say certain things they do not wish to say.

“I’m frankly disappointed that wasn’t a unanimous decision,” Rienzi said.

Elizabeth Clark, associate director for the International Center for Law and Religion Studies at Brigham Young University, discussed a forthcoming article she wrote for the Notre Dame Law Review. She explained that religious freedom in law can be viewed beyond a dichotomy of narrowly tailored exemptions on one side and no exemptions on the other.

Last year, in her concurring opinion for Fulton v. Philadelphia, Justice Amy Coney Barrett questioned whether an approach to religious freedom protections could move away from these poles. Clark argued that it could, suggesting a “non-categorical approach,” one that is rooted in the constitutional rights connected with religious identity and practice.

This approach would establish a normative core of rights for religious or believing individuals. These would include autonomy rights, the right to self-identiy and proselyte, and the right to “reasonable access to creation of tax-exempt churches.”

“I think this could be an important approach to bridge the deeply-set divide between those favoring religious exemptions and those wanting to keep Smith,” Clark said.

A common goal

The Notre Dame Religious Freedom Initiative was founded four years ago. Barclay, its current faculty director, recently clerked for Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch and is currently finishing a doctorate at Oxford.

Last year’s Religious Liberty Summit was held in Rome, where President Dallin H. Oaks, first counselor in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ First Presidency, offered a keynote address. He called for “a global effort to defend and advance the religious freedom of all the children of God in every nation of the world.”

“This is not a call for doctrinal compromises,” Oaks said, “but rather a plea for unity and cooperation on strategy and advocacy toward our common goal of religious liberty for all.”

This year, President Camille Johnson, president of the Relief Society of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, spoke on a panel alongside scholars and other religious leaders, expressing the church’s desire to be a “light” and “leaven” in every nation, even in countries where government may be overtly hostile to religious faith.

“When it is darkest, even a small light can make a big difference,” Johnson said. “So, we believe that the Savior’s injunction — that his followers should be a light — applies to us, especially in times of darkness.”

Deseret News Editor Hal Boyd contributed to this report.