Editor’s note: This story was originally published on May 2, 2020.

SALT LAKE CITY — Steve Starks’ cellphone rang early in the morning on March 11.

The CEO of the Larry H. Miller Group of Companies, which includes the Utah Jazz, was enjoying spring break in southern Utah with his wife and children having canceled a trip to Disneyland as more news about the novel coronavirus started to come out of California.

On the line was Dennis Lindsey, executive vice president of basketball operations for the Jazz, telling him all-star center Rudy Gobert had a fever and flu-like symptoms. The team had Gobert tested for the flu. Results were negative.

Starks and Lindsey stayed in touch throughout the day as the Jazz prepared to play the Oklahoma City Thunder on the road. The 41-23 Jazz were coming off a home loss to the reigning NBA champion Toronto Raptors two nights before and needed a win over the Thunder to hold on to fourth place in the Western Conference standings.

Though the chances of the 27-year-old Gobert having coronavirus seemed slim, the team wanted to be cautious.

About 20 minutes before tipoff in Oklahoma City, Starks’ phone rang again with the news that would change everything: Gobert tested positive for COVID-19. Starks immediately called NBA Commissioner Adam Silver. The Jazz were walking onto the court.

“There was this moment when I was looking at the television knowing what was going on, expecting them to cancel the game at any moment, knowing that Adam Silver and the league were talking about it, and ultimately the word got to the officials and teams were sent back to the locker rooms,” Starks said.

The NBA season came to an abrupt standstill.

“It was some of the most surreal moments of my career, and really did become a switch point for the country. Because the NBA acted swiftly, other leagues followed after that,” Starks said.

“I think it raised awareness for everybody around the country that this wasn’t just a challenge that was going to be overseas, but this was here and that anybody could get it.”

Italy had just placed the entire country — 60 million people — under quarantine to blunt COVID-19. South Korea was furiously trying to contain the virus by isolating thousands of infected people, many of whom belonged to the same church.

Cases in the United States numbered about 1,200 with 38 deaths. Seattle and New York City were emerging hot spots. In mid-March, Washington state had the highest number of confirmed cases in the country until being surpassed by New York. Both were already under states of emergency.

Meantime, sports fans were days away from filling out brackets for March Madness and spring training for baseball was in full swing.

In Utah, Gov. Gary Herbert had declared a state of emergency on March 6, just hours before the health department confirmed that a former passenger on the Grand Princess cruise ship was the first Utahn to contract COVID-19. By March 11, three people were infected in the state.

And for a week before that, Utahns were stockpiling toilet paper, bottled water and food as if the virus were a natural disaster, even as state officials discouraged panic buying.

General conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — one that church President Russell M. Nelson had promised six months earlier would not only be memorable but unforgettable — was just weeks away. It normally brings thousands of visitors from around the world to its Salt Lake City headquarters. But the global church with thousands of missionaries around the world had already suspended business and missionary travel to six countries and kept missionaries isolated in their apartments in South Korea and other COVID-19 hot spots.

Gobert’s positive test propelled a chain reaction. The NBA shut down, and the focus of the state and the nation shifted to combatting a vicious virus that started far away in an open-air market in Wuhan, China.

“That became real for everyone. Public consciousness is almost always driven by symbols, and that became a powerful symbol. Certainly, we all began to realize this was different than we understood it to be,” said former Utah Gov. Mike Leavitt.

The unraveling of the life Utahns once knew started to accelerate.

It was as if the virus pulled the loose end on a ball of string, and just kept pulling until it was in a pile on the floor. And now, no matter how hard anyone tries, it can never be rewound into the same ball.

“I am left wondering what will normal look like and when we will get there,” said Rep. Ben McAdams, D-Utah, who won a nasty battle with COVID-19. He was hospitalized for a week and put on oxygen. He was one of at least five members of the House of Representatives and one senator who suffered from the illness.

Utah took its first deliberate step this weekend to open society toward whatever normal will look like in the future, while cautioning residents against becoming casual over what Leavitt called a “cunning enemy.”

‘Fog of war’

COVID-19 would — and continues to — exact a long-lasting toll on society. More sports leagues, schools, churches, conventions, concerts, restaurants, theaters and a host of other businesses and activities shut down in head-spinning succession after the NBA suspended play.

State and local officials suddenly had to weigh public health against maintaining Utah’s booming economy, though they apparently didn’t know exactly how dangerous the virus could be.

The day Herbert held a press conference with grim-faced state leaders in the Emergency Operations Center at the state Capitol to ban mass gatherings of more than 100, two groups of fourth graders on a field trip filed through the room an hour earlier. The next day, the governor called off public school.

After people spent December through February trying to understand what pandemic means, the next step was to figure out what role everyone played in dealing with it, Leavitt said. It’s not like an earthquake or a big snowstorm for which emergency plans are in place at various levels of government.

“With a pandemic there’s a lot of confusion about whose job it is to do what. There was a kind of great sorting out that occurred in March when we had to reconcile the fact that this is a different kind of disaster than we ever experienced before,” said Leavitt, who developed a federal pandemic response plan while serving as Health and Human Services secretary more than a decade ago.

Lt. Gov. Spencer Cox, the state’s coronavirus point man, described it as the “fog of war” as the state tried to ramp up for the pandemic. Leaders had to make important decisions with little information and access to supplies to carry out those decisions.

From the beginning, officials knew that testing would be critical to slowing the spread but faced a shortage of testing machines and the means to run the tests, as well as nasal swabs and personal protective equipment.

“Something that should take six months and we had just days and hours, and how the hours felt like days. We were just trying every possible resource and every possible option to get the things we knew we needed to figure out where this disease was and how quickly it was spreading,” Cox said.

Initially, the state only had a four-person team frantically working on those priorities, but that expanded to hundreds, many working on very specific issues that most people would never think of, he said.

At one point, Utah had less than a week’s supply of swabs, which would severely affect the amount of testing that could be done, so the coronavirus response team put out a call on social media.

“We have people emailing us about their uncle’s cousin who knows somebody and maybe there’s some in China and we’re running down every lead, and we’re failing,” Cox said.

Finally, Ben Hart found a legitimate lead for 100,000 swabs in Chicago. Like many state workers, Hart, the deputy director of the Governor’s Office of Economic Development, jumped in to do whatever was needed. In this case, procuring hard-to-find supplies.

Though the price for the swabs was 10 times the norm, there was no hesitation to pay for them under the circumstances, Cox said. The supplier had to put the swabs on a truck because there were no flights to get them to Utah. The state even flew someone to Wyoming to meet the delivery truck to ensure the goods were on board.

“Those are the type of crazy things that were happening in the moment and had to happen,” Cox said. “Thank goodness we got those swabs because it would have set us back two weeks if we didn’t.”

Earlier on the day that the Jazz big man tested positive, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints moved its April general conference, which brings thousands of visitors from around the world to Salt Lake City, to a virtual gathering. The church suspended Sunday meetings across the globe a day later and then started the process to return thousands of missionaries serving abroad back to the United States or their home countries.

On Sundays, many members of Utah’s predominant religion now administer the sacrament in their homes instead of in meetinghouses, and that might continue for some time. State leaders say churches and sports and concert venues won’t reopen until near the end of the recovery period.

That the state closed schools and church services were canceled before the coronavirus had spread in Utah like it had in states like New York, Washington and California saved lives, Cox said.

School closure forced teachers to work from home and use a wide array of technology to facilitate learning and keep in touch with their students, some of whom aren’t all that interested in schoolwork anymore. Seniors had their final months of extracurricular activities yanked out from under them and are trying to figure out ways to hold graduation ceremonies without gatherings of students, parents and teachers.

Colleges and universities moved all classes online, booted students from campus housing and canceled or delayed graduations.

State officials prohibited dine-in service at restaurants and shuttered personal-care shops.

Hospitals put off nonemergency surgeries and doctor appointments to get ready for a possible influx of coronavirus patients. Residents wanted to know how and where to get tested for the disease amid a dearth of test kits as well as PPE for health care workers.

Utahns went from not knowing how afraid to be of coronavirus to being largely sequestered in their homes. And members of the media, including the Deseret News, cleared out of newsrooms to work remotely and report using the best practices of social distancing, comparing notes with journalists across the country.

And then the earthquake hit, throwing the response to the pandemic into further chaos.

The 5.7 magnitude quake rattled the Wasatch Front, causing millions of dollars in damage to buildings, including schools and homes. Fortunately, few if any Utahns — schools weren’t in session — were injured in the shaking. But it was jarring enough to get people to start thinking about the “big one” — by once again hitting stores in droves to load up on toilet paper and bottled water.

Four days later on March 22, the health department reported Utah’s first COVID-19 death.

Robert Rose, 79, and his wife of 55 years, Connie, had recently returned from a trip down the Mississippi River.

Connie Rose first got sick on March 17 and immediately became concerned about her husband, who had issues with his lungs after a couple of bouts with pneumonia a decade earlier. Robert Rose came down with symptoms two days later on a Thursday and went to Lakeview Hospital the next day before passing away that Sunday morning.

No one knows for sure he if contracted the infection on the river trip or the return flight to Salt Lake City or after the couple was home.

Staying home

Herbert pulled together some of the best minds across all sectors in the state to develop the Utah Leads Together plan to weather and conquer the devastating public health and economic impacts of the deadly pandemic.

Though Republicans and Democrats at the state and local level say they have worked well together, they didn’t always agree on the best path forward. There were also missteps, such as the state spending $800,000 on the controversial anti-malarial drugs — hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine — touted but not proven to treat COVID-19. (The state ultimately received a refund.)

Cox laments the lack of giving someone the benefit of the doubt for mistakes made in dealing with the pandemic.

“Just knowing that when you’re moving at that speed and you’re doing something like this, you’re going to have to take some chances and sometimes those will pay off and sometimes they won’t,” he said.

As one state after another issued stay-at-home orders and despite demands for Utah to follow suit, the governor resisted. On March 27, Herbert announced a two-week “stay safe, stay home” directive, which he later extended to May 1. Salt Lake City and several counties, including Salt Lake and Summit — an early hot spot — took the governor’s directive a step forward with stricter stay-at-home orders.

All of that seems like a lifetime ago as Utahns over the past two months have home-schooled their kids, worried over household budgets, learned to navigate Zoom or Google Hangouts and turned their kitchens into offices — provided they still have jobs.

Since late February, about 125,000 Utahns, or 8% of the workforce, have been furloughed or laid off.

Though she expects more job separation, Natalie Gochnour, the Salt Lake Chamber’s chief economist, said it’s hard to imagine things getting worse.

“In 42 days, Utah wiped out nearly all of the jobs that our nation-leading economy created in the past three years. More job losses will follow, but I expect April 2020 will be the highpoint for job losses, with each subsequent month tapering down,” said Gochnour, an associate dean at the University of Utah business school.

Following a rough launch, the federal Paycheck Protection Program funneled some $3.6 billion in emergency help to more than 21,000 Utah businesses. Another 18,000 were left waiting in line but hope to get money in the second round of funding to keep people employed.

Utah’s nearly $10 billion tourism industry — which survives on people going places — is suffering more than any other sector, losing about $26 million a day in visitor spending, according to the state Office of Tourism and Film.

“Our research shows the silver lining is that Utahns will choose to savor more of Utah,” said Vicki Varela, managing director.

The state’s scenic wonders in places like the Mighty Five national parks will once again be on display for everyone to see.

“As Utah moves carefully into the stabilization phase of our economic recovery we all have a renewed opportunity to show good stewardship — of each other and our physical safety and of our land and communities,” Varela said. “COVID can’t take away that Mother Nature played favorites in Utah.”

‘Preach hope’

Through all the gloom, people have found ways to lift each other from large corporate donations of needed hospital supplies to pop-up concerts on front lawns — with proper social distancing. Medical professionals from Utah put themselves on the front lines in overwhelmed New York City hospitals.

Dr. Dixie Harris, a critical care and pulmonary physician at Intermountain Healthcare, treated dozens of ICU patients with COVID-19 on the night shift at Northwell Health’s Southside Hospital on Long Island for two weeks.

“This is a very lonely disease,” she said.

Because families weren’t allowed to visit, they asked hospital staff to hold an iPad to the patient’s ear, even those who were sedated, so they could read or sing to their loved ones for hours.

Harris said when she talked to patients who were awake, she would always hold their hands to provide some human-to-human contact, even though she had gloves on.

“I do that here and will continue doing that because even just having somebody’s hand, you can tell when they’re scared because they squeeze the hand really tight,” she said.

Drive-bys have replaced handshakes and hugs in Utah for sending birthday greetings, congratulating newlyweds and welcoming home missionaries. Front-window visits for people in care centers and newborns are commonplace.

The response has fostered a rare sense of unity in action, not just in Utah but across the country, Leavitt said.

Latter-day Saint leaders approved 110 COVID-19 humanitarian aid projects in 57 countries and the church’s bishops’ storehouses are providing goods to food banks across the country. Church members in Utah are in the middle of a project to sew 5 million clinical health masks for health care workers. And the church joined with Catholics and others in a Good Friday day of fasting and prayer, unifying people throughout the world.

Starks said he’ll never forget a phrase the late Larry Miller uttered in a meeting of company executives amid the 2007-08 financial crisis: “All of us have to go preach hope throughout the company and in the community. We need to preach hope.”

As April gives way to May, the state looks to slowly emerge from its cyber cocoon. But it also brings more of the same restrictions — some with even greater emphasis — such as social distancing, hand washing and wearing face masks.

Utahns, by and large, have followed government directives and orders to stay home and keep 6 feet apart in public to help “flatten the curve” and slow the spread of COVID-19, officials at all levels of government say.

Still, some residents have chosen not to follow the rules, failing to observe social distancing in stores, gathering in large groups at parks or refusing to don face covers.

“There’s a certain level of arrogance by some, which is shocking to me, but for the most part it’s been great,” Salt Lake County Mayor Jenny Wilson said. “Just because we’re two months in doesn’t mean the virus is any less deadly.”

Under the Utah Leads Together 2.0 plan’s color-coded risk assessment system, Herbert this weekend shifted the state from “red” or high risk to “orange” or moderate risk, though populations most vulnerable to COVID-19 remain in the red category.

Restaurants, salons, gyms and other shops are reopening provided they strictly follow a list of protocols and precautions. But, the governor said, the onus is on everyone to prevent backsliding into high risk.

“This is not going back to business as usual. We’re not to that point,” Herbert said at one of the state’s daily press briefings last week.

Leavitt likens the next phase to stepping on a newly frozen lake, not knowing how thick the ice is. The only way to move forward is to slide a foot on the ice and listen for cracking, and the ice might be thicker in some places than others.

“There is risk everywhere,” he said, noting that the second wave of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic was worse than the first.

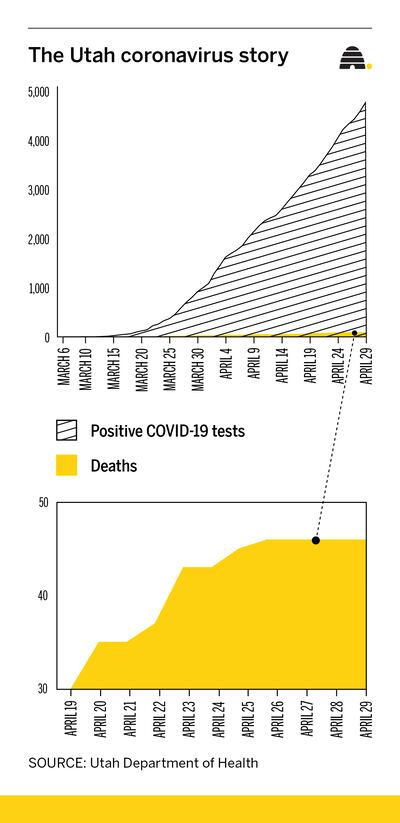

As of Saturday, 4,981 people in the state have contracted the disease and 49 have died. The positive test rate is 4.2%.

Dr. Angela Dunn, the state epidemiologist who worked in relative obscurity, has taken center stage every day to explain how the stealthy virus took a deadly path from Wuhan, China, to the lungs of 24-year-old Silvia Melendez in West Jordan, Utah.

The virus has hit Salt Lake County — the state’s most densely populated county — the hardest, with 2,609 cases and 30 deaths. But health officials there have managed to trace the source of each exposure in 85% of the cases.

An active shooter or an earthquake were among the biggest threats the county was training for prior to the coronavirus pandemic, though the health department had some procedures in place because of the H1N1 flu 11 years ago.

“None of us could have anticipated being where we are today at the end of April having gone through what we’ve been through the last two months and now recognizing we’re not going to exit out of this as quickly as we like,” Wilson said.

She calls it the second-darkest time in her life, the first being when her now teenage son had open heart surgery as an infant.

‘Really scary’

COVID-19 put everyone on a personal journey, she said. People’s financial, physical and emotional health are being tested. Some have lost loved ones. Others have passed away alone in hospital rooms. Medical workers put themselves in harm’s way every day, she said.

No one is immune from the disease.

Relatively young and healthy, McAdams spent a week in the hospital, including a stint in the intensive care unit, with COVID-19. Utah GOP Sens. Mike Lee and Mitt Romney self-isolated for two weeks after coming in close contact with a senator who had the infection.

McAdams, a married father of four school-age children, said the pandemic became real when the NBA postponed its season and “affected us” when schools closed. And it really hit home a few days later when he came down with the virus, even though he was following guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the state when he became ill.

“I think I had maybe a false sense of confidence because when I did get sick, it hit me really hard and it was really scary,” he said.

Through his illness he learned firsthand about contact tracing, which he said many people misunderstand as government following you around and spying on you. It’s really a “sickness coach” or public health professional an infected person can go to with questions about what or what not do to limit the spread, McAdams said.

Contact tracing and testing remain a vital part of being able to reopen businesses, schools, theaters and parks, officials say. While Utahn ranks high nationally for testing, the state has more capacity available than the number of people being tested.

The state now has 62 test sites and three mobile test sites, including one that was deployed to the hard-hit Navajo Nation. ARUP Laboratories, based in Salt Lake City, plans to roll out COVID-19 antibody testing nationwide by the end of the week.

Neither McAdams nor the two senators were in Washington to vote on the $2.2 trillion economic rescue package. GOP Rep. John Curtis was the only member of the Utah delegation to actually vote on the package.

The Utah Legislature used a new law for the first time to call itself into online special session to deal with economic fallout of the coronavirus.

The world is going to change, and that’s part of the emotional and psychological adjustment everyone is struggling to make, Leavitt said.

“There’s never been a pandemic of this size that didn’t have profound impact on the economy, that didn’t rejigger the politics, that didn’t stimulate lots of sociological change, and this one’s going to be no different,” he said.

Watching a Salt Lake Bees game as the setting sun lights up the Wasatch Mountains, catching a new movie on a first date, high-fiving Bear at a Jazz game all vanished in an instant.

Though those things might not mean much when people are sick and dying, they are woven into the fabric of society.

“I think it’s been challenging for people because sports and entertainment are an outlet. It’s a way for people to go be with others in an environment that’s very fun and engaging, that’s uniting,” Starks said.

Homes now have become an even more significant part of people’s lives because it’s where kids go to school and parents work. But, he said, people miss time spent out doing things with others.

Starks said Larry H. Miller feels a “responsibility and stewardship” to get those businesses open as soon as it’s safe.

“We’re not a culture of hermits,” he said. “As strong as our family relationships can be and as meaningful as our home is, there’s still something that happens within us and happens as a community when we can go congregate together.”

Gobert recovered from COVID-19. But it will be some time before fans pack the arena to see him and the Jazz play again. Sports venues will be among the last places to reopen. For now, the state has limited gatherings to no more than 20 to keep from backsliding into the day everything changed.