Greg Bell told me this: We serve as long as the people want us, then we go back to our lives. We don't define ourselves by our positions. Because I was never expected to be here, I don't have that baggage. I'm playing with house money. This far exceeded my expectations. If this is it, then what a ride, and I can't wait to get back to my family. – Spencer Cox

FAIRVIEW — Spencer Cox once turned down Harvard for a less glamorous school and walked away from a lucrative job with a law firm to move back to his boyhood farm. So maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that he came within minutes of turning down an offer to be Utah’s lieutenant governor.

Getting the L.G. job is like winning the lottery in politics, and he was only 38 and a rookie state legislator to boot. Yet he came this close to saying no, and the reason he almost said no can be found in Fairview, population 1,300. You get there by following Highway 89, which winds through the sage and juniper country of Sanpete County, with the snow-capped Manti LaSalles framing the eastern horizon, overlooking green meadows and marshes dotted with cattle, sheep and horses.

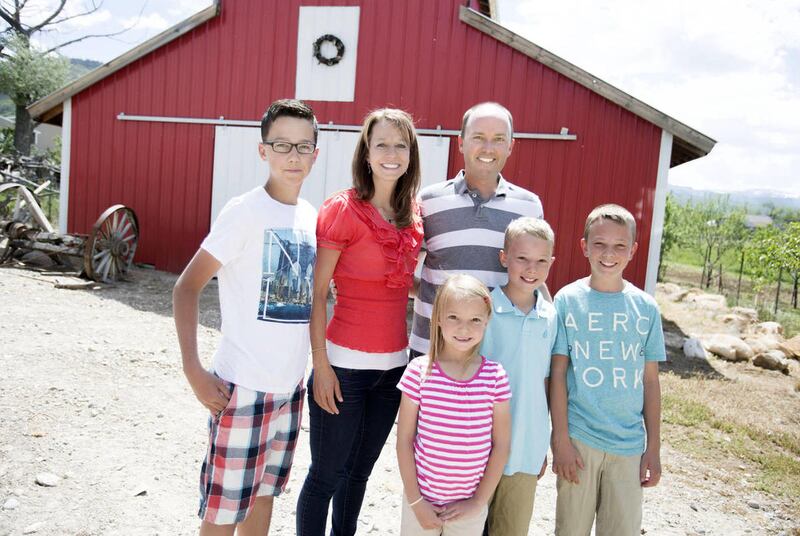

The Coxes live in a Norman Rockwell painting. Their handsome, two-story brick home sits on seven acres that overlook the valley, backed by a small red barn. On a summer day, the only sounds are meadowlarks, aspen stirring in the breeze and the clack-clack-clack of large Rain Bird sprinklers in the adjacent alfalfa fields. Sitting close together on the family room couch, Spencer and Abby can see their four children — Gavin 15, Kaleb 13, Adam 10, Emma Kate 7 — out the large back window racing around the family’s fields on four-wheelers as they do their chores, chased by a convoy of dogs under blue skies and sunshine.

This is why Cox took the huge pay cuts and left the big city and the law firm and a promising law career. This is why he serves as lieutenant governor while living in Fairview and not Salt Lake City. Living in the city didn’t offer many opportunities for their kids to learn to work. So they gave their children sprinkler pipes to move early every morning and hay to bale and gather. They gave them wide, open spaces to roam and dogs to tend and fences to build and mend and their grandfather’s farm to work and large lawns to mow and sheep to herd.

In 2003, at the age of 28, Cox packed it all in and went home again to take over the family business. He went back to family, back to his ancestral home, back to parents and old friends and the land he knew. He moved from the big city back to the farm town of his youth, where the biggest thing in the community is the annual demolition derby, for which the locals camp out to buy tickets.

For 11 years, the Coxes got exactly what they wanted out of the bargain — the farm, chores for the kids, a dream home, more family time. Then the governor called and offered him the lieutenant governor’s job. Anyone else would have been dancing in the small lane that passes below the Cox home.

Cox cried.

Spencer and Abby were both raised in large families on farms in the area, 10 miles apart. She was the fifth of 10 children — eight of them boys — and he the oldest of eight kids. She grew up on a 500-acre ranch, where cows, chickens, sheep, horses and pigs were raised. Spencer grew up on a 150-acre farm that has been in the family 150 years. Spencer’s children are the seventh generation to live here. Their ancestors are buried in a plot not far from their house.

Spencer and Abby, who both grew up on a daily routine of farm chores, attended the same junior high and high school, one year apart, but didn’t become acquainted until his senior year. They began dating after he graduated from high school. They married shortly after he returned from serving a LDS Church mission in Mexico. They both graduated from Snow College and Utah State.

His career was fast-tracked. He was named Student of the Year in the USU political science department, with a perfect 4.0 grade point average. He was accepted by Harvard Law, but chose Washington and Lee University instead because “I just knew I was supposed to be there.” He was hired by the Salt Lake law firm of Fabian and Clendenin. After a few years, he was on track to make partner. The Coxes settled into a subdivision in Kaysville. Four children arrived.

Then they began to question what they were doing. “That third boy really threw me,” says Abby. “I didn’t know what I was going to do with these boys. I worked on a farm. I saw our little quarter acre in Kaysville and wondered how am I going to teach these boys to work?”

Other questions arose. They saw a bumper sticker that read: “It’s 99 percent of the attorneys who give the other 1 percent a bad name.” It started a discussion. “Is the world a better place because of what I do here?” he asked Abby.

“Absolutely not,” she said, taking the direct approach.

If all that weren’t enough, Cox’s father, Eddie, invited him to run the family business in Fairview — CentraCom, a telephone company (now telecommunications) his grandfather bought in 1919 that his family continued to manage after selling it in 2001.

“I’m going to manage the phone company another 10 years,” he told Spencer. “How about moving back here and raising your kids here and take a big pay cut?”

Cox’s peers thought he was crazy to consider such a move. He sought advice from U.S. District Court Judge Ted Stewart, for whom he had once clerked. Stewart, who is from Logan, told him, “If you get a chance to go back home, I promise you you’ll have more fulfilling opportunities to serve the community, your family and the church. You won’t regret it.”

Those words would prove prophetic.

Spencer not only took a 25-percent pay cut by leaving the firm, he gave up the chance to make partner and left a bonus that was nearly as much as his yearly salary at CentraCom.

They lived in Fairview proper for two years and made plans to move into their dream home on seven acres carved out of the old family farm. Before that could happen, Cox received a call from his church asking him to serve as bishop of the local ward. It meant he couldn’t move for five years — he needed to remain in ward boundaries. The Coxes continued to live in town. After serving as bishop for five years, Cox finally moved the family into their new farm home on the bench north of town.

Finally, everything was working out just as the Coxes had hoped. The kids had their farm work, Abby had her dream home, Spencer was making good money again as vice president and general council with CentraCom. Long hours at the law firm had left him little time at home; now he was coaching his kids’ baseball, basketball and football teams and he was home for dinner. The Coxes were surrounded by family, with his father’s home a couple of football fields away from his back door, his brother’s home next door and other relatives nearby.

“Life was good,” he says. “We loved it.”

Then politics called and complicated his bucolic plans. Politics run in the family blood. Their parents on both sides were active civically. Eddie had even served as county commissioner. “We were taught to give back,” says Cox. “There were volunteer firefighters and EMTs in my family.” A political science major at USU, he was soon drawn into local politics.

Cox was appointed to fill a vacancy on the city council for nine months and that was the beginning. He was voted in as mayor and then county commissioner and finally state representative.

Then Gov. Gary Herbert called him, ostensibly to ask for input on candidates to replace Lt. Gov. Greg Bell, who was resigning to address personal financial problems. Later, Cox would learn that Bell had suggested his name to the governor. After Cox suggested several candidates to Herbert, the governor said, “What about you?” No one saw that one coming. Cox had served in the state legislature less than a year. Now he was being considered for an office that could be a stepping stone to the governor’s office (two of the last three governors served as lieutenant governors). LaVarr Webb and Frank Pignanelli, the Deseret News’ political columnist team, listed more than 30 candidates for the job; Cox was not one of them.

Two days later the governor called Cox again and asked to meet with him and his wife. They talked for 90 minutes. Five days later he offered him the job.

“I had won the lottery in the eyes of everyone else,” says Cox. “This was an incredible opportunity out of nowhere ..”

But he was not happy about it. It was, he says, “almost devastating. There were sleepless nights. We had the perfect life, everything we dreamed of. In the interview, the governor said, ‘You’re going to have to move your family to Salt Lake City if you do this.’ Abby and I looked at each other. I said, ‘That’s probably a deal-breaker for us. I felt like we were supposed to move back here (Fairview) for a reason, and I still feel that way.’”

He told the governor he could do the job from Fairview. He would simply commute the 100 miles to Salt Lake City since the position would require him to travel frequently no matter where he lived, and he and Abby had family in the area to help with the children. But Cox was still conflicted; it would also mean being gone for the dance recitals and Little League games.

“We went back and forth,” says Cox of the decision.

One afternoon he was sitting on the steps of his home, waiting for his daughter to return from school, as he often did. He watched her as she stepped off the bus and walked up the driveway toward the door, her backpack slung over her shoulders.

“I just sobbed,” he remembers. “I thought, ‘I can’t miss this.’ At that point I was ready to call the governor. I was 15 minutes away from calling him and telling him no.”

He walked to his parents’ home to discuss the dilemma with Eddie and his stepmother, Lesa. “I asked him for a blessing and then we had a good chat,” he says. “They told me they’d pick up the slack at home, that we were all in this together.”

Since taking the position in October, he has tried to meet the demands of his office with the needs of home. Most days he simply commutes to Salt Lake City. The Coxes’ extended family tends the kids when Abby accompanies her husband for political functions. He is gone all day during the week and sometimes on Saturday. He usually spends one night a week in Salt Lake City.

“I don’t coach the teams and don’t see (Emma Kate) walk up to the door,” he says, “but I tuck the kids in at night and see them in the morning.”

They use technology to cover some of the absences. If one of the kids is playing a ballgame or giving a speech at school, he watches via Skype. He helped one of his sons with a school project via FaceTime, and they emailed the speech back and forth to refine it. He tries to get home once a week to watch ballgames.

“The kids have adjusted well,” says Abby. “They knew it was going to be hard, but they understand it’s OK to do hard things. We have our days that are hard and days that are rewarding. We’re making it work, and we have lots of help. We couldn’t do it without our (extended) family.”

There have been other sacrifices besides family time. After Cox took a big cut to trade the law firm for the family business 11 years ago, he took another big pay cut (50 percent, he says) to accept the job of lieutenant governor. “My wife reminds me that we’re going the wrong direction,” he says. “But we always knew we had to do what’s right beyond the pay.”

Since taking office, Cox is frequently asked the obvious question: Now that the lieutenant governor’s job has fallen into his lap, does he aspire for the governor’s office in two years?

“If you have political ambitions, you don’t move to Fairview,” he says. “Greg Bell told me this: We serve as long as the people want us, then we go back to our lives. We don’t define ourselves by our positions. Because I was never expected to be here, I don’t have that baggage. I’m playing with house money. This far exceeded my expectations. If this is it, then what a ride, and I can’t wait to get back to my family.”

Sitting in their family room, side by side, the Coxes survey the scene outside the window — the sweeping fields and the mountains and the children working. Everything Stewart predicted has been fulfilled: the opportunities to serve community, family and church.

“Not a day goes by that Abby and I don’t look at each other and wonder what we are doing here,” he says. “How did we get here? It’s so humbling and overwhelming.”

Doug Robinson's columns run on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. Email: drob@deseretnews.com