While they waited for their flight, Drew and Jan Simmons sat in front of the Salt Lake City International Airport’s vast plaza windows, gazing out across the massive construction site below.

Drew Simmons said it was like watching a new version of “Toy Story,” likening the busy dump trucks and excavators — looking like miniatures in the distance — to Tonka trucks.

“There’s so much to see,” Jan Simmons said.

The two have watched the construction from those same windows ever since the massive new airport opened its doors in September as they make the pit stop in Salt Lake City from Twin Falls, Idaho, on their way to Arizona to visit family. They make the trip about every three to four months, and say it’s been fun to watch the progress.

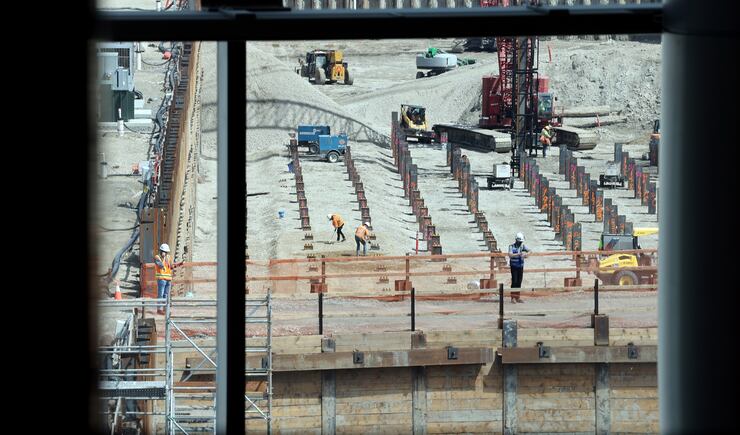

The bustling construction site — with an enormous ditch where a future tunnel will provide a more convenient connection between the two new concourses — used to house Salt Lake’s old airport, before it was demolished to make way for more expansion. Where the old terminals once stood, concourses will branch out to the east to host even more gates.

All that is left of the former travel hub is piles of rubble, which crews were still pulverizing in the distance while the Simmonses watched on Monday morning.

Jan Simmons said she still has some lingering nostalgia for the old airport.

“But I’ve got to tell you,” she added, looking around her at the new facility’s plaza, its sky-high ceilings and windows, its shiny new floors and seating areas. Its sheer size. Everything — brand new. “This is so beautiful and so efficient.”

A generational project: Not done

When the new, $4.1 billion Salt Lake City International Airport opened its doors to travelers on Sept. 15, Utah leaders and national airport officials lauded it as a generational project ushering in the future of air travel, in spite of the upheaval from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Preceded by decades of planning, the new airport wasn’t just envisioned to replace an aging facility that was buckling under its own weight. It was originally built to serve 10 million passengers. In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it served more than 26 million.

It was envisioned to mean much more to Utah and its capital city: to be a gateway to the rest of the world that would last for decades. Large enough to accommodate 34 million passengers. Grand enough to position Utah as not just the crossroads of the West but the crossroads of the world. Spectacular enough to act as an impressive window for the rest of the world into Salt Lake City, which is looking again to put itself on the global map by bidding to host a future Winter Olympics, likely in 2030 or 2034.

Its grand opening was met with somewhat of an anti-climactic reception thanks to the pandemic, as a fraction of the people were flying then. Since then, air travel has begun to return with a vengeance.

Bill Wyatt, airport executive director, recently described to the Deseret News and KSL editorial boards the eerie sight of standing on the skybridge on the way to his office, looking out across the airport and “not seeing another soul” for at least 20 minutes at a time.

In 2019, about 28,000 to 30,000 people a day passed through the airport. But in March and April of 2020, that number plummeted to about 1,200.

“It was kind of an alarming period,” he said. “It was not clear to us when life would return to some semblance of normality.”

But as the U.S. begins to emerge from the pandemic, business and leisure travelers have begun to return to the skies. On May 15, Wyatt said the airport saw 23,000 passengers walk through its doors. “So pretty good volumes.”

The grand September opening was just the beginning. There’s much more to come for the enormous new hub.

Wyatt, in a Zoom call with the editorial boards, rotated his camera to show cranes and construction crews outside his office window.

“That’s the old airport that we’re building on top of right now,” he said, describing how crews are now installing stone columns, pilings and plumbing for the eastern half of Concourse A.

“We’re a little ahead of schedule,” he said, though he added he “always hates to say that because I’m sure something will catch up with us.”

There’s a lot more to come for the new airport, including some changes that should help address one of travelers’ biggest complaints: walking distance.

The central tunnel

While not expected to open until 2024, Wyatt says the central tunnel — its precursor trench clearly visible from the terminal plaza — should help cut down on walk times, especially for those needing to get to gates on Concourse B.

Currently, travelers must walk down the west side of Concourse A to get to a temporary tunnel, a “mid-concourse” tunnel built in 2004 in anticipation of the future new airport, and will later be used for behind-the-scenes employee access once the central tunnel opens.

“So every passenger today goes out through the checkpoint, walks out to the center of the plaza, turns left, either they get on a plane that’s on the A Concourse, or they go out through the tunnel to the B Concourse,” Wyatt said.

From there, those flying out from Concourse B must either find their gate or get on a bus to get to a “hard stand” airplane (planes on the tarmac and not at their own gate. Officials say the setup allows airlines to be flexible with flight capacity as demand grows).

“So the distances are considerably greater,” Wyatt said. However, “when we’re done with this (central tunnel) phase ... everybody will have the same experience.”

When that tunnel opens, passengers will walk through the plaza on Concourse A, either turn left or right depending on their gate, or walk straight through the central tunnel to get to Concourse B. It will include moving walkways.

“It will significantly reduce the amount of walk time that is required in order to get to your gate,” Wyatt said.

The tunnel could also feature a tram in the distant future. In the meantime, a set of electric carts may be utilized to help transport people.

“The original concept ... was that the train would probably not be built until there was a C Concourse (added to the north of Concourse B),” Wyatt said. However, the quarter-mile distance between concourses for a train is “not a very long distance and there is some question about whether it would function effectively.”

“But that node exists,” Wyatt said, “and it’s entirely possible that we’ll set up the airlines to actually do this to operate a set of electric carts going back and forth.”

“The possibility of carts in the new tunnel is very real and something that is very much under consideration at this point,” he said.

The central tunnel will be 990 feet long and exceed 106,000 square feet, with a price tag over $120 million, according to the airport’s website.

The entire tunnel will also feel like one giant interactive piece of artwork. Designed by Gordon Huether, the same artist behind the airport’s centerpiece art installation “The Canyon” lining the ceiling of the terminal, “River Tunnel” is meant to resemble water that flows through Utah’s canyons. Blue light and water sound effects will submerge passengers in the “River Tunnel” as they walk through.

Compare it to the LED tunnel at Detroit Metropolitan Airport, which immerses travelers in 700 feet of lights set to musical scores.

The world map, saved

As passengers emerge on Concourse B, they’ll find themselves in a miniature version of the plaza back at the main terminal, with a second installment of “The Canyon.”

They’ll also find an Easter egg from the old airport, one that airport officials originally thought they wouldn’t be able to salvage: the iconic world map that was on the floor of the old Terminal 1.

As crews began demolition, they found that under a layer of concrete beneath the map, the artist had placed a fiber mat barrier when it was created in 1960 that allowed for safe removal of the map.

“When we saw that, we thought, ‘You know what? We can save this,’” Wyatt said.

Artists and contractors sawed it into 2-foot squares, numbered them, and saved the pieces.

“It’s over in one of our warehouses now,” waiting to be put back together, Wyatt said. He said the contractor told him when it’s put back together, “you’re not ever going to know that it was apart.”

“When Concourse B is done and the central tunnel is done, there will be a mini-plaza ... and (the map) will be right in the center of the main plaza at grade. You’ll walk right on it,” he said.

“It’s just very exciting for us,” Wyatt added. “We were able to save it and, you know, it’s the only old part of the airport that will be left is the world map. And that seems somewhat fitting.”

More gates

Along with more artwork, the new airport will also be getting even bigger.

A lot bigger.

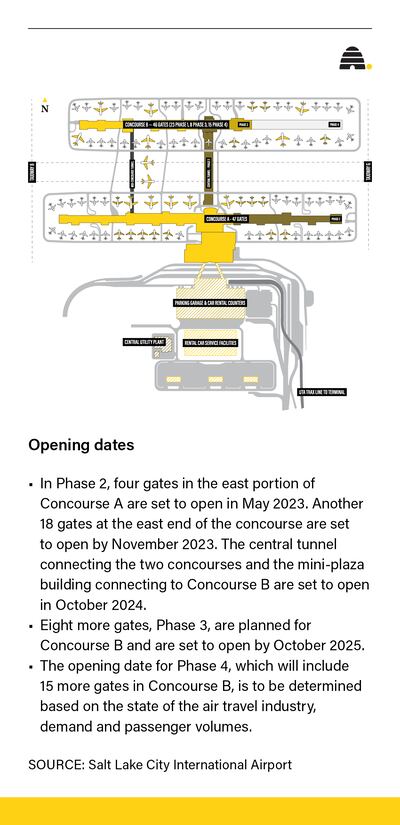

Let’s start with Concourse A. By the end of 2023, what airport officials are calling “Phase 2” will be complete with the addition of 22 gates on the east side of the concourse. The gates will extend over the land where the old airport once stood.

Crews will start by building four gates, which are slated to be completed in May 2023. Then the rest will be built and opened incrementally, Wyatt said, set to be done by the end of November 2023.

While the central tunnel and the mini-plaza connecting Concourse B are expected to open in 2024, eight more gates planned for the east side of Concourse B, as part of “Phase 3,” aren’t scheduled to be completed until October 2025. Four of those eight gates (those on the south side of Concourse B), will phase in sooner, expected to open October 2024.

After those eight gates are complete, still more gates are expected on Concourse B, but airport officials don’t have a timetable yet for that work.

What’s planned for the long-term is “Phase 4:” 15 more gates on Concourse B. A completion date is dependent on the state of the air travel industry, demand and passenger volumes, according to airport spokeswoman Nancy Volmer.

Even further beyond that, airport officials have space and capability to build a third concourse north of Concourse B — but that’s far into the future.

Wyatt guessed that Concourse C is probably “a decade away.”

“In airport planning world, we don’t set dates. We look at volume; that’s what drives decision-making,” Wyatt said. “So if we can look out into the future and see volumes increasing at a predictable rate, that intersects with that planning level, that’s when the button gets pushed for a Concourse C.”

But before they can embark on building that third concourse, Wyatt said the Delta hangar, the air traffic control tower, the fuel farm, maintenance hangars and the SkyWest hangar will all have to be moved.

“We’re doing our master plan now on where all that stuff will go,” Wyatt said, “and what do we have to do to make that happen so that when the day comes for Concourse C there won’t be anything in our way.”

Clarification: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the remaining 22 gates planned for Concourse A would be finished by the end of 2024, based on information provided by airport officials. The story now reflects updated information provided by the airport saying those 22 gates will be open by November 2023.