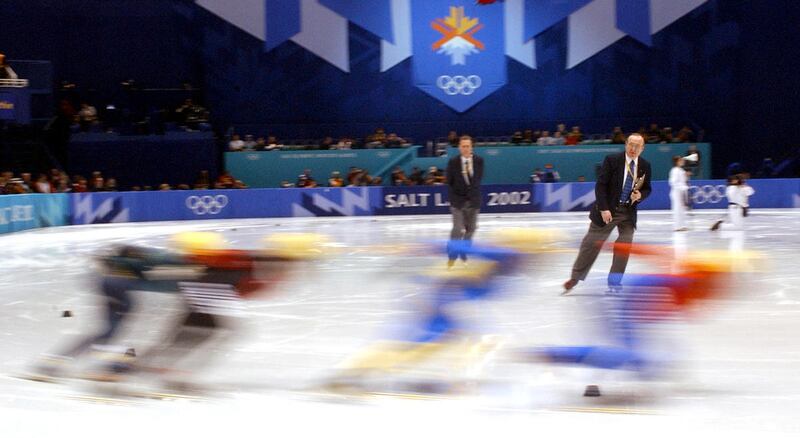

PARK CITY — On most days, the track surrounding the Utah Olympic Oval’s ice sheet and rinks is littered with runners, while elite speedskaters train adjacent to an adult hockey league and elementary school students learning to skate.

Halfway around the world, Sochi’s Adler Arena — which hosted the same Olympic events during Sochi’s 2014 Games as the Utah facility did in 2002 — sits empty in an Olympic Park that locals have dubbed “a museum of corruption,” according to local journalist Alexander Valov.

The difference in what happened to these two world class facilities after they were home to Olympic moments is in how organizers viewed not only the possibilities for the facilities, but what the legacy of the Games should be to the communities that hosted them.

While most Olympic cities see the venues built to host the Games as competition and training sites for elite athletes, Utah’s organizers had a different vision. And it is that reason, they say, why structures built to host the 2002 Olympics continue to benefit the entire country today.

“These facilities should serve the community,” said Colin Hilton, president and CEO of the Olympic Legacy Foundation. “These Olympic venues serve a variety of types of athletes. There are a lot of hours in the day. … Our whole philosophy is all ages, all abilities.”

That strategy resonates — even among those who won medals at the Utah Olympic Park in 2002.

“It’s such a functional facility with so many purposes,” said Tristan Gale Geisler, who won gold at the Utah Olympic Park’s track as a skeleton racer in 2002. “It’s great for both the athletes being able to come up and have really quality events, down to tourists who just want to go up and try it or see it.

"Now they have the tubing, the zip lines, the museum — it’s just a very, very functional place. A lot of other tracks, that’s all they do. But there are only so many lugers and bobsledders and skeleton athletes in the world. For Salt Lake to make a facility like that that can be used and enjoyed by so many, that’s significant.”

That strategy was developed when hosting the Games looked more like a wish than a real possibility. It took shape when organizers chose to see the Games as a way to spark Utah’s growth in the sports industry, not a way to capitalize on it.

Unique Utah plan

Hilton, who moved to Utah in 1999 when Mitt Romney took over managing the Games, said Utah’s approach isn’t the only thing that is unique among Olympic cities.

“The history is unique in how they paid for and maintain the venues,” he said, noting that it really started in the 1980s when Salt Lake officials first began efforts to bring the Olympics to Utah. “We’re doing this so differently than everybody else around the world.”

Cities have a variety of ways they handle post-Games management of facilities. The most common options are for the government to continue running the facilities or selling them to private companies. Neither offers the community much return for the investment that comes from hosting the Olympics.

In New York, Lake Placid’s facilities, for example, are run by a government entity, where Adler Arena in Sochi was sold to a private company that is now teetering on bankruptcy as the Russian economy flounders.

“We’ve done it differently, as only Utah did,” Hilton said. “We didn’t want to have a legacy foundation out there asking for taxpayer funds to help pay for operating sports facilities.”

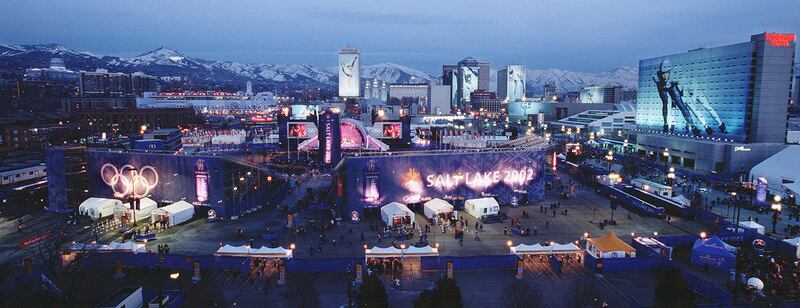

When Salt Lake City was chosen by the United States Olympic Committee as the official winter bid city, organizers asked voters to approve a $59 million loan to build the Utah Olympic Park, the Utah Olympic Oval in Kearns, and the Ogden ice sheet. They promised to pay the money back and pledged to raise and maintain a $40 million endowment fund that would sustain those facilities.

The voters said yes, and between 1991 and 1993, the facilities were built. For the rest of the events, existing and improved facilities were used. Keep in mind, Salt Lake City wasn’t awarded the games until 1995.

Before the facilities were even finished, organizers and state officials agreed that a nonprofit would run Utah Olympic Park and the Utah Olympic Oval after the Games.

“Our success afterwards came from being an independent nonprofit where we can be nimble and creative in what we do and how we find sources of revenue,” Hilton said, noting they’re not subject to the ebb and flow of government generosity. “I couldn’t do that as a government entity, how we’ve created all of these public activities that help us pay for all the facilities and sports programs.”

Still, it costs more to run the venues than they make. So the Utah Olympic Oval, the Utah Olympic Park, and as of last year, Soldier Hollow in Midway, are subsidized by the Olympic Legacy Foundation’s endowment, which came from the revenue of the Games.

“We’re very fortunate,” Hilton said. “When there is an economic downturn, we don’t have to close our doors or scale back. The foundation rides those waves of an up and down economy.”

Utah’s success in capitalizing on the Olympic Games isn’t just in the brick and mortar of buildings. It’s in the efforts of the Utah Sports Commission and individual ski resort owners to hold onto the spirit of the Games by continuing to host World Cup and world-class sporting events.

Cooperation between private businesses, like ski resorts, the Sports Commission, the Olympic Legacy Foundation and the governing bodies of sports like U.S. Ski and Snowboard and U.S. Speedskating, has led to the continued use of the venues for National Championships, World Cup and World Championships.

'Secret sauce'

On this 15th anniversary of Utah's 2002 Olympic Winter Games, there seem to be more events than ever. Last weekend, Solitude hosted the first snowboardcross World Cup in the U.S. since 2013, as well as a Nations Cup skicross event. This week at Soldier Hollow the first Nordic Junior World Championships is occurring in the U.S. for the first time since 1986, when Lake Placid hosted.

And Deer Valley is hosting what’s become an annual World Cup, and according to Australian mogul skier and World Cup leader Britteny Cox, the event is “the Superbowl” of freestyle events and a favorite of the athletes.

“One of the things (we) wanted to show the world is that we’re ready to host another Olympics,” said Bill Stenquist, chairman of the organizing committee for the Nordic Junior World Championships. “We want to show the FIS (International Ski Federation) that both our ski jumps and our cross country trails are in very good condition, and that we have the organizational structure to host these big events.”

Sports Commission CEO Jeff Robbins said the reason Utah has succeeded where other host cities have failed is the partnership between government, private groups and companies, nonprofits and national governing bodies.

“It’s a remarkable thing,” said Robbins, whose group is responsible for helping to lure hundreds of sporting events to Utah. “It’s very unique. Calgary would maybe be the closest thing to what we’ve done, but they haven’t replicated what we’ve been able to do in the summer space.”

While most sliding sport athletes, as well as speedskaters, have returned to Winter Games sites around the world, Utah’s stops are among the favorites, in part because Hilton said they open them to allow the world to train here.

Four-time Olympian Emily Cook, who now coaches with the U.S. aerial ski team, said no Olympic ski site has done what Deer Valley has in establishing itself as the premier stop on the World Cup tour.

“I don’t know that I’ve been back to any of the other sites,” said Cook, who competed in Turin, Italy, Vancouver, Canada, and Sochi, after missing the 2002 Games with broken feet. “It’s huge. This place has brought up so many athletes since then … and athletes from every nation love coming here.”

Robbins calls it “Team Utah” and said the accomplishment is that they’ve been able to sustain and expand on the Olympic legacy for 15 years with plans to continue in hopes that if the country or world ever needs world class accommodations, they provide them.

“What we’ve built, the partnerships, it doesn’t exist anywhere else,” he said. “It’s kind of our secret sauce. It’s kept Utah ready, willing and able to host these major international events.”