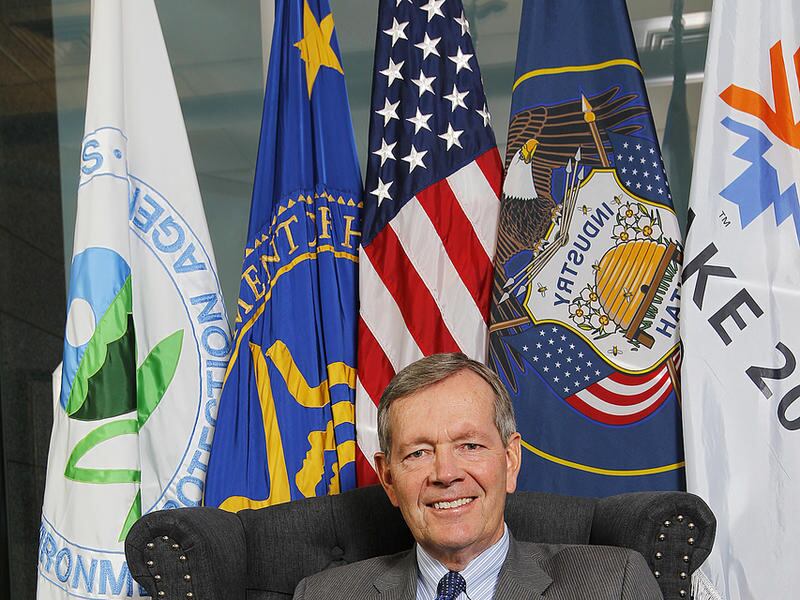

SALT LAKE CITY — In Utah history, few have gone as far, met as many, seen as much or accomplished more in the political arena than Michael Okerlund Leavitt. He was elected governor three times, including the biggest landslide victory in state history (73 percent of the vote in 1996). He was head of the Environmental Protection Agency in the first George W. Bush administration. He was a member of the Cabinet as secretary of Health and Human Services in the second Bush administration. In 2012, he was hand-selected by Mitt Romney to lay out an administration blueprint for a Romney presidency. If/when that came to pass, he was considered the presumptive chief of staff in the White House.

When that didn’t happen, he left the nation’s capital to return to Utah and organize Leavitt Partners, a consulting firm with just under a hundred employees and offices in Washington, D.C., Chicago and Salt Lake City that advises health care businesses and other stake-holders how to negotiate the nation’s health care system.

It’s been quite a run so far for the 64-year-old former governor, who grew up in the 1960s in Cedar City, where, he says, “If you took ‘Leave it to Beaver’ and crossed it with ‘Bonanza’ you’d have my childhood.”

He was the oldest of six boys belonging to Dixie and Anne Leavitt. He helped with the family insurance business, wrestled cows on the family ranch in Loa and played football, basketball and baseball every other available minute. “To this day,” says the three-term governor and former Cabinet member, “I still don’t remember feeling any more anxiety in my entire life than walking to the window of the Iron County Record at 6:30 in the morning to see if I made the Little League team.” (He did).

On a recent afternoon at his office that overlooks the Salt Lake Valley from the top floor of the Wells Fargo Building downtown, Leavitt agreed to sit down with the Deseret News and talk about where he’s been, what he’s done, what he’s run and where he’s going.

DN: Thank you for your time and willingness to share some of your views. Yours has been a mostly political life. Why politics?

ML: I had no intention to pursue politics until my father decided to run for governor in 1976. The plan was I would stay in Cedar City and try to help keep the family’s business moving. I ended up managing his campaign because we couldn’t find anyone who would work harder or cheaper than me. I was 25. Dad didn’t win, although I think he exceeded people’s expectations by quite a bit. That experience exposed me to the world of politics, and then a whole series of events ensued that led me down the political path.

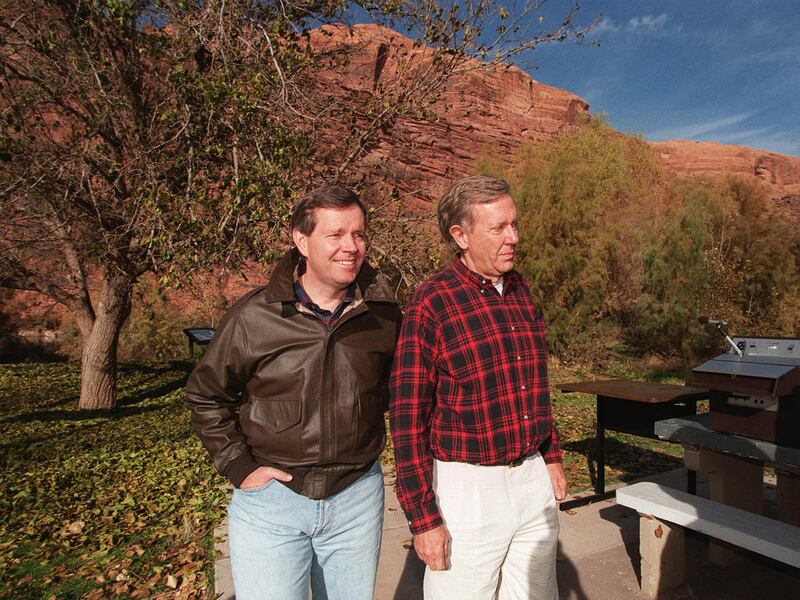

DN: As governor, you struck up a friendship with George W. Bush? How did that come about?

ML: I was elected governor in 1992 and in 1994 became chairman of the Republican Governors Association. The job of chairman is to help other people who are running for governor. That was the year George W. Bush ran in Texas, so I visited with him several times and helped him as best I could. He won. And then, as it turns out, Texas and Utah are close in the alphabet order of the states and I often sat next to George Bush at governors meetings. We found we had a lot in common and intuitively liked each other, and we began to form a friendship.

DN: When did you first become aware that your new friend might become president?

ML: He won re-election (in Texas) in 1998 and shortly after that people began to talk about him being the nominee in 2000. He called me one day and asked if I’d like to go on a trip to Israel with him. Four of us went, there was George W. Bush, Paul Cellucci, the governor of Massachusetts, and Mark Racicot, the governor of Montana. We just had this incredible period of time together. We visited the Sea of Galilee and other holy sites and talked about things that were important to us and what we had in common — two Catholics, a Methodist (in Bush’s case), a Mormon (in mine), and our Jewish hosts. People began to notice that George Bush was there, you could hear them talking about him on the street. The two of us were walking through the old city and turned around a corner and a Palestinian merchant was sitting there next to a barrel of mustard seed. He looked up and said “Boosh.” From that time forward I would call him Boosh and he had nicknames for me too. I wrote in my journal, “Today I saw fate fall on a man.” To me it was a moment when he realized he had become a world figure, not just a Texas figure, and there was a greater sense of leadership potential for him.

DN: Ever considered a run for the presidency yourself?

ML: I don’t suspect anyone who has been a political figure the length of time I have hasn’t thought about that. So I would confess, yes. But so much of it is timing and the timing has never been right and likely never will be right. If you think about the periods of time when it would have been logical for me to run for president, George W. Bush was running in 2000 and I had determined to run for a third term as governor. By 2004 I was a member of the Bush Cabinet. In 2008 there was a man named Mitt Romney who had invested a lot of his own resources and was running. I had just come out of the Bush Cabinet. The president (Bush) had been through some rugged years and being a member of his Cabinet would have required me to separate myself in ways I found unattractive. Then in 2012 I was very much behind Mitt. So at some point you have to be realistic about how much of your life you are prepared to devote to something where there is a relatively modest chance of succeeding. I had remarkable opportunities in public service that I will always be grateful for.

DN: How can Republicans get the White House back in 2016?

ML: I am among those who find the current situation quite perplexing. My experience has taught me that there are constants in the world and that reality has to be contended with. There’s a limit to the period of time that non-realities can continue. So I have optimism that over a period of time the chaos will begin to diminish. (Donald) Trump is a real factor and he’s representing a constituency that feels an appetite that he fills. I think we’re in a critical state in our democracy and it’s going to be fascinating to see who the aggregate mind picks. But it boils down to the fact that in a democracy people get the leaders they choose. While I was governor, the state of Minnesota elected a professional wrestler as their governor. Who would have thought that would happen, but it did.

DN: During the Romney-Obama race, you were in Washington setting up a mock Romney administration in the event of a win in November. What was that experience like?

ML: I would say that was among the most stimulating six-month periods of my life, politically. We built a great ship, regrettably it never sailed. I had the privilege of implementing a new law called the Presidential Transition Act of 2010. In 2012 it was the first election when that law would be effective, so we had the benefit of that. We spent roughly six months creating a federal government in miniature and we were ready to govern. We had three basic tasks. One was to staff the government with competent people, the second was to create an agenda for the first 200 days based on what he (Romney) had committed to do, and the third was to conduct the operations of the president-elect during the 71 days between the election and the inauguration. We created literally a day-to-day playbook on what would occur for the first 200 days of the administration. And the truth is, we thought we were going to win, maybe naively, but it felt like we were planning the leadership of the free world. We had 600 people working and we were ready. We were more ready than any administration in the history of the United States.

DN: Would you have been White House chief of staff?

ML: Some people thought that to be logical, but the truth is, selecting a chief of staff was a decision for the president-elect to make on the day after the election — not before. Mitt Romney was properly focused on getting elected, and I think we all felt it would be bad form and probably bad luck to have conversations about any appointments before the election. So we never had a conversation about chief of staff.

DN: You had names picked for every vital position in the administration. Did anyone know their name was on the list?

ML: We had created options for the most important roles. There were a lot of people who hoped their name was on the list, but the lists were known to only three or four people. Mitt never saw the lists.

DN: In your view, should Mitt Romney run again?

ML: I’d like to see Mitt Romney be president. He would be an extraordinary president. But I think the mechanics behind Mitt becoming president at this point are a bit problematic.

DN: You first met Mitt Romney when you targeted him to run the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics that were riddled by a bribery scandal. What are your reflections on a period of time that began amid crisis and controversy and ended with one of the state’s most shining moments?

ML: I’ve reflected a lot on this — what can we learn from it? This is probably not the forum to articulate all those things. There was a lot that happened that was unfair both to the community and individuals who had their lives and reputations damaged, and that is regrettable. But, with a decade and a half perspective, I think the Olympic movement was improved. A badly needed fresh wind swept through and changed an institution that had become full of hubris and had lost sight of its noble goal and purpose. It was a bruising time for our community, but I think the community demonstrated real character in recognizing the only way to overcome was to put on the best Winter Games in history. We accomplished that. Lots of people should be credited with the vision to do it, the tenacity to get the bid, and then literally tens of thousands of people who participated. There are so few times when an entire state has its heart beating in unison over the same thing, and this was one of them. The experience brought maturity to our state and a new confidence. We realized we could compete with anyone in the world and win.

DN: Your views in a nutshell on Obamacare?

ML: There are a lot of things I would do differently in health care. A lot of things. I’d start with the way it passed. Anytime you have a bill with the votes of one party only it’s not going to be the best outcome. Those who wrote the bill had a very different philosophy than mine. Obamacare tries to use government to operate far more than I think the government is capable of doing competently. Likewise, the cost of it can be criticized. However, I’m not one who falls into the category of saying it’s all bad. It was a positive thing to have something happen because the system was desperately broken and needs to be fixed. I do know this intimately. Sometimes having just motion allows things to reshape. Interestingly, I think some of the unintended consequences of the law have produced some valuable improvements. The country will continue to reshape health care over the next decade. We can’t continue to spend the percentage of our income that we are now. We have to find a way that we can get high quality at a lesser price. Society continues to work toward those things, and I think things will change over time.

DN: What do you miss about being governor? About being a member of the Cabinet?

ML: I miss the ability to see big public problems and having the ability to fix them. I miss mixing it up in the world of ideas and the democratic process. But I also miss the unique interaction a governor has with people. Because people respect the office of governor, the holder of the office can make a big difference in individual lives. You can lift people up in individual ways. You could encourage people, you could put your arms around them when they’re hurting, once in a while you could challenge them in ways they found important later. Somehow, when “the governor” does or says those things it has a little extra impact. It was such a privilege and I miss being able to contribute individually to people’s lives like that in a slightly magnified way. If I’m completely candid, I also have to confess that I miss skipping TSA at the airport.

What I miss most about being a member of the Cabinet is the opportunity of representing the United States of America. I’ll never forget the first time I represented the president and our country on a world stage. I was assigned to lead a delegation to a large meeting in Japan. Over 100 countries attended. Everybody had to make an opening statement of about five minutes. By the time they’d gone through 75 countries, people were worn out, walking around, going to sleep. It was finally my turn. I sat behind a sign with the words “United States of America” written on it. When I spoke, everybody stopped. The place went absolutely quiet. I looked around and felt conspicuous by this sudden silence. And then I realized, it’s not me, it’s the sign I’m sitting behind. I’m speaking on behalf of the United States of America and the world is listening. Few have that privilege, and I’m grateful I did.

DN: So what’s next on your path?

ML: When I left the government I decided to go back to building businesses. So, some colleagues and I formed Leavitt Partners. I spend most of my time, in one way or another, thinking about the future of the health care system. Our clients pay us to help them figure out where they fit in a rapidly changing health care system. Or, in some cases, the health care companies to invest in. I’m also on the board of directors of several companies. I do some volunteer work for my church and still pitch in politically now and again. Perhaps my most important endeavor is looking for opportunities to distinguish myself with the 14 grandchildren that are now a big part of life for Jackie and me.