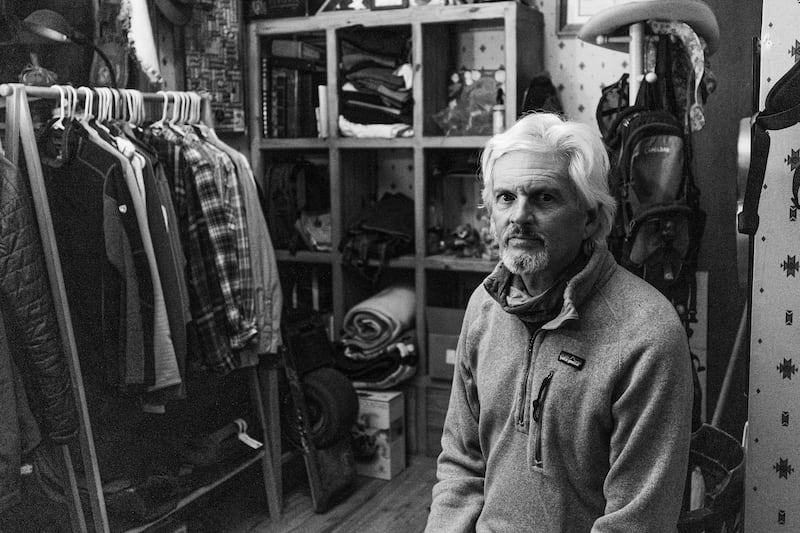

On a snowy, wintry afternoon in December, around 4:30, I was sitting in the Aspen Highlands Ski Patrol locker room. While trying to ignore the smell of dank, sweaty boots, I eavesdropped on a conversation between an old-time ski patroller and a young lift operator.

The liftie was lamenting his current situation: living in his truck, washing up at the rec center, occasionally catching warm nights and hot showers at a new girlfriend’s place. There’s nowhere available or affordable to live.

The older guy empathized. He’d squeezed into affordable housing back in the ’80s and was still under the same roof. Skating on the margins of the town where he’d pegged his career. “It was hard when I started, and I think it’s much harder now,” he said, checking his watch to see when he’d have to catch his bus down the valley.

That struggle is backed up by math. There’s a metric called the Gini coefficient that measures inequality by plotting dispersion of income. A Gini coefficient of 0 indicates perfect equality while 1 means total inequality.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent American Community Survey, the national Gini coefficient is .48. Aspen’s is .56.

Megan Lawson, an economist at the Headwaters Institute based in Bozeman, Montana, who studies community development in the American West, says it’s an indicator for how far apart the haves and have-nots are. She uses it to try to capture the experience of people working in communities like Aspen, and to quantify why it’s hard for them to keep pace when expenses like housing and health care keep rising.

Those disparities are wide and getting wider across the West. According to the Colorado Center on Law and Policy’s self-sufficiency standard published in 2018, in Aspen’s Pitkin County, a family of two (an adult and a preschooler) needs an annual income of $71,274 to make ends meet. That’s way above the 2021 federal poverty benchmark of $17,420 for a family of two, and the highest standard in the state. The Pitkin county manager has found that a quarter of households fall under the standard. In a picture-perfect utopia, one in four families is struggling to pay their bills.

Maybe it sounds like what’s happening in your local community. Because it’s not just the dirtbag ski patrollers who are having a hard time. And it’s definitely not just happening in Aspen.

I was in that locker room because I spent the past few winters on the road, writing a book about the appeal of skiing, and the reality of living in mountain towns. And when I was there, I found a lot of darkness. The book, which started as a love letter to a sport that has shaped my life, quickly evolved into an investigation of the inequality I found, and the way it’s winnowing down any kind of middle class and making it harder to thrive if you’re not at the top of the income pyramid in the West — and more broadly, in America.

Places like Aspen — and other resort towns like Jackson Hole, Wyoming, or Park City, Utah — might seem like rarefied dreamlands where the standard of living is unrealistically high. But the growing gap between wages and wealth is a national trend, and what’s happening to the locals in ski towns is also what’s hollowing out the middle class across America: flat wages, consolidated wealth, governmental austerity and an increased cost of living.

According to data from Pew Research Center and others, inequality is real and getting worse across the country. Ski towns, with their skewed baseline of desirability and reliance on service workers, provide an interesting lens into the high highs and low lows of that inequality. They’re the canary in the coal mine for how a top-heavy economy can’t hold itself up, and how that imbalance trickles into everything from mortgage rates to mental health.

It can feel grim, but the bright side is that those towns are also trying to address some of those issues fast — because they have to. So in the face of that, maybe there are some lessons for the lowlands, too.

In 1894, local minders pulled a 2,340-pound silver nugget out of Aspen’s Smuggler Mine, the area’s final foray into a high-dollar heyday. Back then it was an industry town, booming and bustling. But extraction bottomed out before the economy turned to skiing.

In the beginning of the 20th century, when the mines tapped out, the town’s population shrank from 10,000 to 750. Aspen was dead quiet until the late ’30s and early ’40s, when skiers started poking around the mountains and running a rope tow up the face of Roch Run, on what’s now Aspen Mountain, in the middle of town.

Chicago socialite Elizabeth Paepcke showed up in the first wave of skiers. She came in 1938, hitched a ride up the back of the mountain, skied down the face, and became enamored of the place and its potential as a ski area. In 1945, she convinced her businessman husband, Walter, who had become wealthy manufacturing cardboard containers, to move to Aspen and invest in the nascent ski operation and the idea of Aspen as a destination.

They connected with a wave of recently returned war veterans who had seen the ski towns of the Alps and wanted to create something similar. Walter worked with former 10th Mountain Division soldier Friedl Pfeifer to plan the first ski lift in town. In 1946, they founded the Aspen Skiing Corp. with two other 10th Mountain veterans, Johnny Litchfield and Percy Rideout.

Walter built the airport and started laying down groundwork for Aspen’s growth, spinning it out into a Promised Land, trying to envision what it would look like when outsiders like him started, hopefully, flooding in. It was a version of the lauded American dream: If you build it, they will come.

They did, and the same was true of the rash of other ski areas springing up across the U.S., many of them started by other 10th Mountain Division soldiers. As the ski industry, and really the tourism industry in general, grew in the middle of the last century it bolstered a new kind of economy, based on leisure time, exploration and recreation.

In the ’60s and ’70s, as thousands of local ski hills sprung up in cold, mountainous towns, skiing became a way for middle-class families to get outside in the depths of winter. It was accessible and wide ranging. But toward the end of the century, as ownership consolidated, and mountainside real estate became more desirable and valuable, the sport — and the towns became more exclusive and expensive.

Aspen, as a ski town, was supposed to be paradise. The Paepckes and the other people who turned Aspen into a tourist destination conceived it as a place where people could get away from their everyday lives to consider higher truths. But any kind of utopia is inherently exclusive. If you have something desirable and limited, like a crystalline valley in the Rockies, capitalism doesn’t do much to keep it untouched and gorgeous. Demand quickly outguns supply, tipping the scales toward excess. When you put bounds around a place to keep it pristine, you’re pushing certain things, and certain people, out of town.

If you’re visiting a ski town, you might not think about the embedded economics — I don’t often think about these things on vacation — but the outdoor industry is an $887 billion economy in the U.S., and it’s growing. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in Colorado, it’s 2.5% of the state’s GDP. In Utah, outdoor recreation contributes more than $4.9 billion in GDP and 61,890 jobs, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Recreation has long been lauded as a way to help wean Western towns away from extraction and a new way to use natural capital, but it can become a chicken-and-egg cycle. You need the buzz of a resort (or many) to pull people in and keep the engine of recreation going.

That can be a good thing: There wouldn’t be many jobs in a valley like Aspen without the resort, and nearby towns like Somerset, which never embraced tourism after the mines closed, struggle with retaining jobs and residents. But it’s an industry that caters to outsiders, and that single-sided, wealth-based economy can crush the culture that it feeds from. And that’s true of industries far beyond skiing, from manufacturing to education.

In her research, Lawson has found that across the West people are moving to counties with recreation opportunities more quickly than to other places — and there’s faster job growth in those towns. But if you pull apart the numbers there is darkness there. Abundant growth doesn’t always lead to equitable growth.

The Aspen area is a good example of that. According to Pitkin County, in 2021, the average income was $49,460, while the state average was just over $63,026. In Pitkin, wages for accommodation and food services, the sec- tor that encompasses essentially any kind of tourism job as well as many service jobs, were $49,460.

“Tourism has the most jobs, but they pay the least,” says Rachel Lunney, director of Northwest Colorado Council of Governments Economic Development District.

She says those discrepancies cascade out in all sorts of complicated, deceiving ways. For instance, unemployment rates are low, which is often a sign of economic vitality, but in Aspen, it’s a false signal of stability. Because the basis of the economy is lower-paying service sector jobs, to make ends meet, people tend to work more than one job — a statistic that isn’t usually tracked. They might be employed, maybe even more than full time, but they’re struggling to earn enough to get by, and that’s true among service workers across the country, from big cities to isolated rural towns.

Wage growth has been sluggish in the U.S. for the past 40 years, and Lunney says that local wages haven’t changed much either. They’re barely keeping pace with inflation, and while wages have stagnated, other sources of income have surged into the county.

In the past decade, remote work options have skyrocketed, increasing 400% since the pandemic. And in the face of COVID-19, knowledge workers flooded out of cities in droves. People who are making money in, say, Silicon Valley, can move to Aspen without directly needing to derive money from the local economy, which has accelerated economic disparity.

It was already bad before it got worse. Former Pitkin County Mayor Mick Ireland did a study a few years ago and found that from 1970 to 2017, while average earnings per job grew 30%, per capita income grew 301%. In November 2021, Pitkin’s per capita income was $155,067 — more than three times the average wage, which means that most of the earnings in the county weren’t coming from wages or the local economy. Instead, Lunney says they’re likely coming from things like investment income, dividends and retirement income, and other accruals of outside wealth, especially after COVID-19 hit and more remote workers moved in.

“It’s really hard to track people who are making money in other places but spending it here, and living here,” Lunney says. And those people who make money elsewhere fundamentally change how goods and services are valued, and how the local economy is stacked up.

For instance, that average wage of $49,460 won’t get you too far in a town where the typical home value is $2.5 million, which it was this year in Aspen — up 19.4% over the past year, according to Zillow. Almost everything else in town, from health care to taxes to groceries at one of the town’s two markets, is more expensive than the rest of the state, according to the county.

Again, it’s not just Aspen. This spreading disparity is happening across the country, and it’s getting worse. According to data from the Economic Policy Institute, U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, as the cost of living has gone up and wages have stayed flat, it’s harder for everyone (besides the wealthiest) to get by.

Jackson Hole, which has the nation’s highest per-capita income from assets according to a study by the Economic Innovation Group, is a clear case. Because Wyoming doesn’t have personal or corporate income taxes, Jackson Hole has become a tax haven for the wealthy. When they set up residency there, they get the double benefit of a ski house (which they can often cover with tax write-off money), and a highly reduced tax burden.

Jonathan Schechter, a Town Council member and economist who studies inequality in ski towns, says that means the county has some of the highest per-capita income in the country, and a massive wealth gap. According to the Economic Policy Institute, the top 1% of earners in Teton County, Jackson Hole’s home, make 132% more than those in the bottom 99% — the highest income disparity in any county in the country.

“Roughly 85% of income earned by Teton County is investment income, leaving 15% for wages, and that’s not much,” he says. He says that makes it hard for most locals to make ends meet, and that makes it hard for them to invest in the community, and their tax base can’t cover their local needs for things like school funding or social services, even when there is a lot of wealth in the area.

Jackson is far out on the end of the spectrum, but what’s happening there is indicative of what’s happening in a lot of other places, from Steamboat Springs to Salt Lake City: It’s becoming harder for an average person or family to make a living. When wages aren’t high enough to support the cost of living and there’s no one to work base level jobs it hollows a community out.

The place where that erosion shows up most clearly is in housing. The standard logic of the free market is to let whoever is willing to pay the most set the value for a good. That logic fails, or at least becomes deeply unequal, in towns where real estate prices are driven by imported funds and earning potential isn’t aligned with the cost. The market breaks down because the value of goods and services is distorted by both desire and ability to pay, and that means local workers can’t find places to live. Families of four are crammed into small, deed-restricted apartments or cramped single-bathroom houses — with parents driving a 15-year-old vehicle hours into town to get to work — all while bringing in a household income that could provide “normal” middle-class comforts were they in Illinois or Oklahoma. For growing young families — or any locals for that matter — there’s nowhere to grow up or move to.

Across mountain towns, real estate prices are sky high because much of the inventory is in sprawling second homes, corporately owned mega mansions and condos converted into Airbnb rentals. For many of the people who own those homes — like an increasing number of businesses, or those 50-plus billionaires who have places in Aspen — price is basically irrelevant. But their ability to snap up desirable real estate makes things nearly unlivable for people who don’t have that privilege and who are often the people keeping the town running. It’s why entry-level workers like the Highlands liftie can’t find a place to live.

In Mammoth Lakes, California, only 2% of long-term rental houses are vacant, which means places to live are nearly impossible to come by. In Telluride it’s 1%. According to a local newspaper article published in July, 59% of Jackson Hole locals say they’re struggling because of the lack of housing. They live in their vehicles, or drive in from Idaho, braving the curves of Teton Pass on storm days. In Aspen, there was violence in a park-and-ride lot, where people were living in their cars, when one man threatened others with a hatchet. There’s underlying grimness in holding on to these picture-perfect towns, and this is part of a bigger story that’s playing out across the country when the working class can’t live where they work.

There are other factors beyond just local wealth that make it hard, like global supply chain issues and the way climate change is pressuring viability via things like water supply. Even if you eliminate from the picture those buying a second home, there’s a geographic crush that makes growth expensive. Development costs are high, and, in places hemmed in by swaths of public lands across the West, there’s not much room to build. Housing is driven by supply and demand, and when it’s impossible to create supply, the demand escalates.

Megan Lawson, the Headwaters researcher, found that 45% of Americans have had their housing prices skyrocket for reasons similar to what’s happening in Aspen. “Communities across the country, in every state, are grappling with housing prices increasing at a rate that has not been seen before, even during the housing bubble that led to the Great Recession,” her September 2021 report read.

As the costs of basic needs like housing grow, the economics becomes untenable for many. People can’t survive on their wages, employers struggle to find workers and some very basic needs get neglected because there’s no one to fulfill them.

“The impacts of record-setting rises in housing prices reverberate through a community and manifest as labor shortages, increased homelessness and dramatic increases in rental costs. Those who are priced out of homeownership today will struggle to build wealth for themselves and their children, exacerbating income inequality,” Lawson’s report says.

I’m an older millennial. Generationally speaking, our parents could generally do better than their parents. Now we only have a 50-50 shot to do as well as our folks.

As my peers move into middle age — which historically comes with middle-class earnings — the majority of us are falling behind past generations. According to a recent Brookings Institution study about the future of the middle class, there are a bunch of factors that are making it tough.

People my age and younger saw steep earning declines right when we were trying to get on the curve of building wealth. Stagnant income and falling wages mean that there is minimal upward intergenerational mobility — a factor that used to be consistent for 90% of Americans, regardless of social class. The cost of traditional tickets to financial stability, like higher education or buying a house, has been rising faster than wages. We are getting lost in the spread of inequality, and that has trickle-down effects. So local governments, town planners, major employers and more are trying to figure out creative ways to make their towns more livable.

One of the most prominent, immediate ways this is happening in Aspen is through an increase in wages. Over the past few years, Aspen Skiing Co., the area’s biggest employer, has repeatedly increased its minimum wage. In November, the company bumped it to $17 an hour, by way of a $3 million payroll investment. Several other major ski world businesses, including Vail Resorts, have also increased minimums to $15.

It’s an economic trend, driven by both inflation and necessity, that’s also happening in cities like Seattle, and in parts of the federal government. In 2022 the minimum wage for federal contractors will be $15, thanks to an April 2021 executive order. Employers of all sizes are realizing — especially in the face of the “Great Resignation,” where more than 34 million people quit their jobs in 2021 alone — that they have to invest in workers if they want to retain them and keep the wheels turning.

To address the housing problem, towns are trying a range of tactics, from deed-restricted workforce housing to job-based housing taxes, to building boarding houses so they immediately house seasonal workers. They’re working to both create more options and make the current ones more affordable. It’s going to take all those tactics and more, because it’s a multifaceted social problem, not just a supply and demand issue.

In December, Aspen hit a wall and the City Council declared an emergency six-month moratorium on new residential land use permits and froze new Airbnb listings. Residents’ opinions were mixed, in part because development is a big part of the local economy, with contractors and construction workers depending on the work. But the council said that the “character of certain development activities in the city of Aspen is having a negative impact upon the health, peace, safety, and general well-being of the residents and visitors of Aspen” and that a freeze would let them figure out a way to adapt codes and regulate growth. “It’s just hitting a level of crisis sooner than I expected,” Tyler Wilkinson-Ray, a local film- maker and photographer says.

The crisis has reached a fever pitch because there weren’t regulatory preparations before it happened, and there are no easy solutions now. Locals are hoping it’s not a case of too little, too late. In her research on economics in the West, Megan Lawson found that the hurdles to adequate housing were the same barriers that prevented equity across the board: unequal wealth and decision-making, and lack of investment in community resources. “Tools we used previously — like inclusionary zoning and incentives for builders — weren’t keeping up before, and they certainly aren’t now. We need bigger, coordinated investments sup- ported at the local, state and federal levels,” the Lawson report read.

Those big, coordinated investments can come from hyperlocal solutions, like the free public transportation in Aspen, which makes more housing easily available, or from federal level changes, like the low-income housing credit in the “Build Back Better” legislation.

But it can’t all come from top-down change. Community organizations, businesses and citizens have to engage as well, to outline and plan for the services and actions that they need. For instance, in Aspen, those Highlands patrollers are part of a union. They’re ahead of a trend of collective bargaining for ski patrols. This year patrollers at Big Sky and Breckenridge voted to unionize. They joined newly formed unions at places like Stevens Pass and Park City that are advocating for fair pay and benefits, because the system currently isn’t working for them. By asking for things like increased minimum wages and year-round health insurance, they’re hoping that can trickle down to issues like housing and health care. And that’s happening at businesses and in industries far beyond the ski world, too. In the past year, workers at places from Amazon to the Audubon Society have voted to unionize because their workplaces and work culture can’t sustain them.

Change will have to come from every direction, from tax policy to town planning. Rees says working toward equity and a high standard of living for the middle class and beyond is going to take a reframing of what we want our towns — and our societies — to look like. “We need zoning policy and density,” she says. “We can’t let nostalgia stop us from making a decent future.”

One light in the canary-filled coal mine is that when towns do let go of their nostalgic ideals of what their town used to be and work collectively toward smart growth and equity, things can change. In 2007, Durango, Colorado, decided to cap the number of short-term rentals in town. Now, only 2 to 3% of housing there can be used for short-term rentals — leaving more than 95% of rentals in town available to local workers, and city planners say they’re constantly getting calls from other communities about how to implement similar programs.

It remains to be seen how Aspen City Council’s Hail Mary could change the livability of the town, but they know they have to do some- thing. And if those places can figure it out, their plans can be a blueprint for how towns across the country can adapt and change, to keep their communities — and future generations — healthy, housed and secure.

This story appears in the February issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.