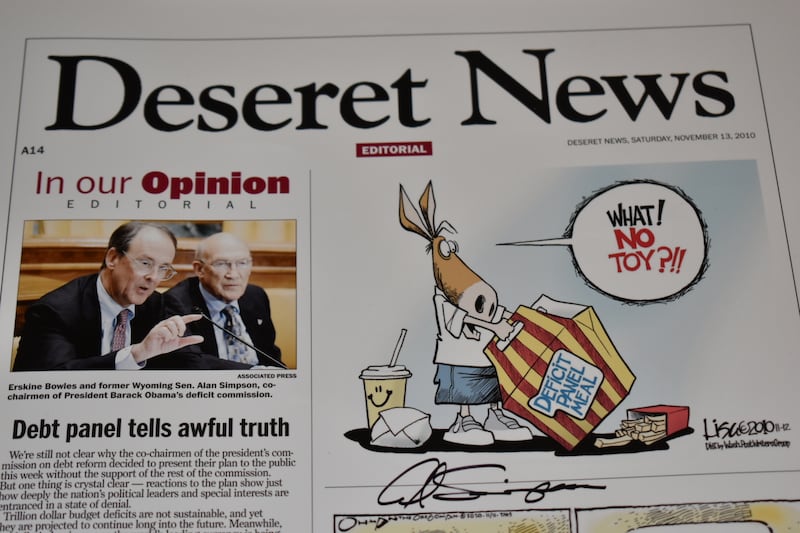

I was cleaning my office the other day when I came across a rare piece of history. It was a page proof — a printout of an editorial page generally used for editing — dated Nov. 13, 2010, and it featured an editorial I wrote in support of the Simpson-Bowles plan to reduce the nation’s debt.

It was signed by former Wyoming Sen. Alan Simpson, the Simpson part of that team. He had visited the newspaper and wanted to show his support for the piece.

The timing of this find was instructive. In recent days, the Biden administration has begun touting its plans for various tax increases, presumably to begin offsetting the enormous costs of multiple COVID-19 stimulus packages, the latest of which is projected to cost $1.9 trillion, as well as a proposed $3 trillion economic recovery plan.

Earlier this month, on ABC’s “This Week,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen talked about taxing corporations and the wealthy more, and she wouldn’t rule out a wealth tax on assets above $50 million.

In an interview with George Stephanopoulos, President Joe Biden said his plan is to raise taxes only on those earning more than $400,000 per year. Earn anything less and “you won’t see one single penny in additional federal tax.”

But then, last week White House press secretary Jen Psaki clarified that this income threshold would apply to families, not individuals. People who earn $200,000 would be hit if they are married to someone earning the same amount.

If anyone thinks this plan would reduce the national debt, they don’t understand history and they haven’t grasped the enormity of the problem.

Nor do they understand the pain that would be necessary, from both sides of the political aisle, in order to make real inroads.

Nor do they understand politics. Biden’s plan hasn’t even a hint of bipartisanship in it. Republicans are almost certain to oppose it, rather than to work on a compromise. As the American Society for Public Administration noted in an editorial for the PATimes, running for reelection has become so expensive that members of Congress spend much of their time raising money.

“It is hard to build relationships across the aisle when you are constantly fundraising for your next campaign,” it said.

Standing in opposition to a tax hike supported only by Democrats could be good for Republicans fundraising.

Which brings me back to Simpson-Bowles.

By 2010, Simpson, a Republican, had retired from political life. So had Democrat Erskine Bowles, who had been chief of staff to President Bill Clinton. This separation, plus their impeccable political bonafides in their respective parties, made them ideal choices to head what President Barack Obama was calling The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform.

To understand why Obama wanted to form such a commission, you need to step back a year. In the spring of 2009, only weeks after Obama had been inaugurated, a loosely organized group called the “tea party” had begun to emerge. On April 15 of that year — income tax day — these groups staged rallies nationwide.

I attended one in Salt Lake City, held in a driving spring snowstorm outside the Federal Building. The mood was as much anti-Republican as it was anti-Democrat. Activist Glenn Harlan Reynolds described these rallies in a Wall Street Journal op-ed as “a post-partisan expression of outrage,” and the outrage was aimed at the bailouts of the great recession and other profligate spending.

To put it in further perspective, at the time Obama formed the Simpson-Bowles commission, the national debt was $12 trillion, or $39,831 for every American citizen (about $48,000 in today’s dollars), according to usdebtclock.org. The debt-to-gross domestic product ratio was 85.5%, and the annual budget deficit, fueled by those bailouts, was $1.3 trillion.

Today, the national debt is $28 trillion and rapidly rising. That calculates to $84,974 for every citizen, and the ratio to GDP is 129%. The annual budget deficit is $3.2 trillion.

And nobody is rallying against this anywhere in the country, especially after four years of Republican leadership that added greatly to the debt while fueling (other than a pandemic slowdown) general economic prosperity.

Today, interest rates are low. As a result, interest payments on the national debt, despite recent increases, remain low, as well.

But at that debt level, even a small increase in interest rates would jar the economy. This could result in higher inflation, beginning a dangerous spiral. Those who have invested in U.S. Treasury bonds would demand higher interest rates to compensate for increased risk. The result would be unemployment, economic hardship and a weakening of the nation’s ability to protect itself and its interests abroad.

If that day comes, politicians will have trouble hiding. People might wonder aloud why neither side took Simpson-Bowles seriously.

In retrospect, the Simpson-Bowles recommendations represented a rare political feat. They provided meaningful and workable solutions to the nation’s growing debt problem that would have required a bit of pain from all sides. It dealt in specific details, not in easy-to-fudge generalities.

It would have raised Social Security’s retirement age to 69 and reduced benefits, but only for the nation’s youngest workers at the time. Wealthier retirees no longer would have gotten the same benefits as those who need money the most.

It would have cut defense, cut farm subsidies, increased the federal gas tax by 15 cents a gallon and removed tax deductions for things such as interest paid on mortgages. The broadening of the tax base would have allowed a reduction in marginal income tax rates. The highest rate was proposed to be 28%. Today’s highest rate is 37%.

It would have capped government spending at 21% of GDP, and forced all government agencies to cut their discretionary spending to 2008 levels, after accounting for inflation.

Significantly, it would have cut $2 to $3 for every $1 it raised through new taxes. Too often, Congress takes tax increases, such as the one Biden is proposing, and uses the extra money to expand programs, rather than to reduce overspending.

But the plan was dead on arrival. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called it “Simply unacceptable.” Republicans said they wouldn’t accept any sort of tax increase, period. Even President Obama, who had created the commission and charged it with finding a solution, wouldn’t embrace the recommendations.

In fact, the commission itself was divided. While Simpson and Bowles wholeheartedly embraced the recommendations, only 11 members of the commission agreed, and that was short of the 14 needed for it to pass.

Simpson and Bowles released the report, anyway. They may have violated protocol by doing so, but they gave Americans a rare, realistic glimpse into the kind of plan that would be needed in order to get serious about fiscal responsibility in Washington.

The plan predicted it would have reduced the national debt by $3.9 trillion by 2020. The nation’s debt-to-GDP ratio was predicted to be 60% by 2023 and 40% by 2035.

Imagine if the nation had been in that kind of a healthy situation, heading into the pandemic a year ago. It would have been better able to respond without raising worries about an eventual day of reckoning.

Instead, since 2010 we have had year after year of partisan bickering and increased spending.

Sometimes, 11-year-old editorials can teach us a lot. The one I wrote, and that Simpson signed, said the plan was “the type of thing a bright CEO might devise in order to save a failing business. It’s also a plan that doesn’t attempt to spare Americans from the awful truth.”

By comparison, Biden’s plan is more of the same — a way to raise money without any hope of reducing expenditures.

But the other side has absolutely nothing to offer in return.

Someday, history may ask why we didn’t act more responsibly while there still was time.