He’s organized and detail-oriented. He has a feel for calling the defense on game day. He’s been assisting with the calls for a few years. He’s been a sharp, valuable asset up in the box. – Utah coach Kyle Whittingham, on Morgan Scalley

SALT LAKE CITY — When Morgan Scalley first approached Kyle Whittingham, his former coach, about entering the coaching profession, his mentor warned him.

“Are you sure about this?” he told him. “Does your wife know what it’s going to require — the long hours and the time away from home? Be sure this is really what you want to do.”

Scalley began as an unpaid staff gopher. That was 10 years ago. In January he was named defensive coordinator, capping off a rapid rise in the profession.

“If I hadn’t gotten into it as young as I did, I probably wouldn’t have done it,” he says. “The only people who understand what you go through are the ones who have done it.”

Scalley had to work long hours and every grunt job along the way — study hall duty, coordinating the weight and training rooms, overseeing the comings and goings of LDS missionaries and writing letters to them, watching over newly arriving players, organizing leadership retreats. He carried a variety of titles: administrative assistant, graduate assistant, recruiting coordinator, safeties coach, special teams coach.

Whittingham identified Scalley as a future defensive coordinator early on and considered him for the job a year ago before talking 71-year-old NFL veteran John Pease out of retirement for the second time. “I told him (Scalley), ‘Your time will come,’” says Whittingham. “I just felt he needed one more year.” When Pease retired for the third time at the end of the 2015 season, Scalley got the call.

“He’ll be a good one,” says Whittingham. “He’s organized and detail-oriented. He has a feel for calling the defense on game day. He’s been assisting with the calls for a few years. He’s been a sharp, valuable asset up in the box.”

Scalley earned Whittingham’s respect for studying the game’s nuances as an all-conference safety for Utah’s unbeaten 2004 team when Whittingham was the defensive coordinator. Scalley studied film and picked up tendencies even then, and refined the skill as a coach. He remembers the thrill he experienced the first time he picked up something on film as a coach that paid off in a game. Before a game against UCLA, he noticed that every time the Bruins’ tight end lined up in the backfield he tipped off the play. If his inside foot was outside the offensive tackle, he remained on that side of the formation to block; if his inside foot was inside the tackle, he would cross to the other side of the formation.

“So we decided, why not blitz the safety if we know he’s going away to the opposite side?” says Scalley. “We went with it and got a big sack off of it. It was the first time that Kyle said, ‘OK, let’s go with something Morgan is seeing.’ It was a nice feeling. I had studied film and it had paid off. You get hungry for more.”

Scalley, a 36-year-old father of three, is nothing if not ambitious. Early on in his coaching career, he told Whittingham he wanted to be a defensive coordinator in five years and a head coach in 10.

“I never thought about it since I told him that,” says Scalley. “A lot of it is put your head down and shut up and listen and add value when you can. I learned a lot from a lot of different coaches, and I’m still learning.”

Scalley, a graduate of Highland High just a few miles down the road from the Utah campus, graduated magna cum laude with a 3.96 grade point average and a degree in communications as a junior at Utah (he also served an LDS Church mission to Munich). He completed the first year of his MBA program during his senior year while helping the Utes finish No. 4 in the national rankings.

“He was tough as nails and smart,” says Whittingham, who was Scalley’s position coach for a season. “He was as prepared for a game as any player I’ve had come through here. He was a lot like Eric Weddle (now in the NFL). Few guys have that ability to dissect an opponent, and it carried over into his coaching.”

Scalley was the poster boy for the NCAA’s student-athlete model. He was a second-team All-America safety and a two-time, first-team Academic All-America. He was awarded two postgraduate scholarships and named the 2004 Anson Mount Scholar Athlete of the Year, which is presented to the nation’s top student-athlete. At the East-West All-Star Game he was presented the Pat Tillman Award, which honored character, intelligence, sportsmanship and service.

Scalley says he was a serious student largely for the same reason he excelled in football — “I’m competitive.” He made a point of not letting his professors know he was a football player.

“I wanted to surprise them,” he says. “I wanted to compete. I didn’t want any preconceived notions, positive or negative. When they did find out, the majority of them were shocked.”

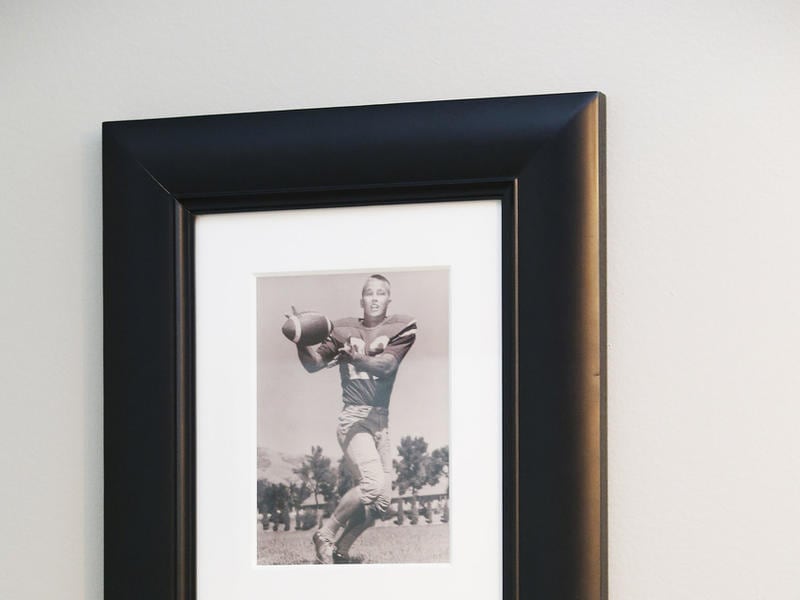

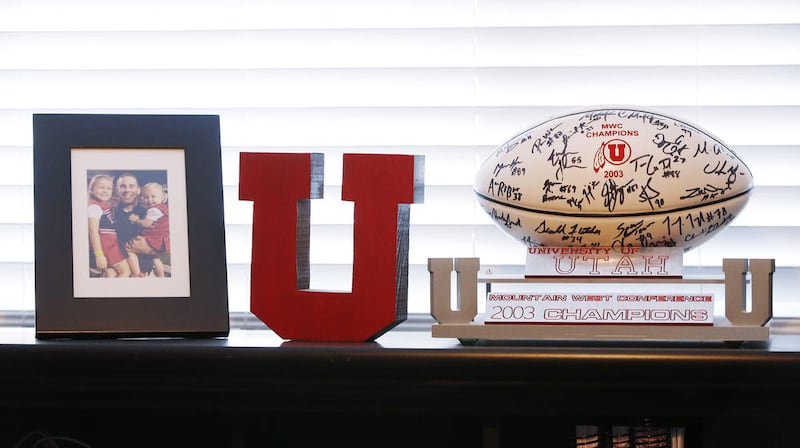

Scalley’s mix of athletics, academics and religious service was the norm in his family. All five of Bud and Claudia’s children were academic and athletic, and four of them served LDS Church missions. Sarah is a skier, tennis player, golfer and runner. Taylor played rugby at Utah. Rachel was a dancer. Scalley’s twin sister Cathryn was a sprinter for Utah’s track team. Bud played halfback for Utah and scored the lone touchdown in a loss to a strong Merlin Olsen-led Utah State team in 1962.

“We’re a competitive family,” says Scalley.

After completing his eligibility at Utah, Scalley failed to stick in tryouts with the Philadelphia Eagles and Buffalo Bills. He returned to Utah and took a job selling tickets for the Utah Blaze, the local Arena League football team. The Blaze wanted to sign him as a player, and after considerable deliberation, Scalley agreed. The Blaze and Scalley held a press conference announcing that he would join the team. He never did.

Scalley consulted Whittingham and Urban Meyer, his head coach who had since moved to Florida. “I wanted to get their thoughts on whether Arena ball was worth it,” says Scalley. “I loved the game, but at the same time I didn’t want to waste my time.” The coaches presented him with the tough questions, among them: Could he progress as an Arena player and reach the NFL? They also offered him administrative positions on their coaching staffs.

“I thought about it a lot,” Scalley says. “(For months) I thought about it and prayed about it with my wife. She was pregnant. If I was going to do this, with all the hours required, I wanted her support.”

On the day of the Blaze’s press conference, Scalley’s wife Liz had a miscarriage. “It was a tough time,” he recalls. “It made me think again about what I wanted. I had more and more conversations with Kyle and Urban.”

In the end, he decided he wanted to get back in the game — on the sideline. He accepted a job as an administrative assistant on Whittingham’s staff in 2006. A year later he became a graduate assistant. Neither job paid. He went two years with little income other than a stipend — the equivalent of his football scholarship — while finishing his MBA, completing an internship at KSL-TV and working part-time at the Wasatch Youth Correctional Facility.

He arrived at a crossroads after the 2007 season. He needed a job, especially after Liz had a baby, and he began weighing business options outside of coaching. “I had to decide what I was going to do,” he says. “I got done with that GA year and my wife and I said, here it is,” he says. It was now or never — get a paying football job or get out.

An opportunity presented itself when safeties coach Derrick Odum left for SMU. Scalley applied for the position and then waited for six weeks. “I was unemployed, sitting at home,” says Scalley. He decided to fill the time by creating a recruiting binder to show Whittingham he would be ready immediately to take over Odum’s recruiting area in Texas. The binder included all the high schools in the Houston area and information about potential recruits. He went into the interview and offered the binder to Whittingham. He got the job.

“It’s not the usual path to a coordinator job,” says Scalley. “Usually, it’s a lot longer. Things have just worked out for me. I’ve been in the right place at the right time and with the right people. I work hard but also I’m smart enough to realize I’ve been lucky. People really took a chance on me, Kyle being the first. I realize how blessed I am.”

As defensive coordinator, Scalley is filling the same job his boss held before he became head coach, but if he finds that intimidating or uncomfortable, he doesn’t let on.

“He’s a defensive genius,” says Scalley. “He can come into a room and make you feel dumb. … He lets us do our jobs. If he feels like he’s getting a good bead on things, he’ll tell you — ‘I like this. I like that.’ But he doesn’t take over. Every week he sits down and asks us what we’re doing and why we put it together the way we did. If he feels like we’re missing something, he’ll ask about it.

“Sometimes I’ll try to get creative and do things that make sense to me, but can the kids get it? Kyle has helped me understand it’s all about the players and what they can grasp. Some might cringe when the head man comes into the room. I love it. I go to him and ask, ‘What do you think of this?’”

As Whittingham warned, it is an all-consuming job almost year round. Scalley doesn’t have time for much TV when he gets home from work, preferring instead to devote all spare time to his wife and children. He credits Whittingham for giving his assistants time to go to church on Sunday and for sending them home immediately after practice, except for Mondays and Tuesdays, so they can be with their families.

Scalley has his own ways to break up the grind of coaching. He plays music in the defensive staff room and, between bits of work, he stands up and puts on a floor show, singing and dancing (if Scalley has a regret it’s that he didn’t participate in high school plays and musicals).

“This job requires so much sacrifice and time that you gotta make it fun,” he says. “I love music and dancing. When I know things are comfortable is when I stand up and start singing and dancing and no one pays attention to me. That’s when I know they’ve gotten used to me.”

Doug Robinson's columns run on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. Email: drob@deseretnews.com