Rep. Chris Stewart has some unfinished business as he steps down this month after nearly 11 years representing Utah’s 2nd Congressional District.

The Republican congressman started working on legislation earlier this year that would make it illegal for social media platforms to provide access to children 14 years old and younger. It’s an extension of his efforts to address a mental health crisis among adolescents, including sponsoring a 988 telephone number for the national suicide prevention hotline that went live last summer.

“The evidence of destructive outcomes for young people is just irrefutable,” he said in an interview as he begins to button up his political career.

The age verification proposal has bipartisan support and Stewart hopes to pass the baton to someone who could see it through. But it takes time, and his last day is Sept. 15.

Also on his to-do list is reforming the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which he says government agencies misused to justify spying on the Donald Trump campaign and on hundreds of thousands of Americans.

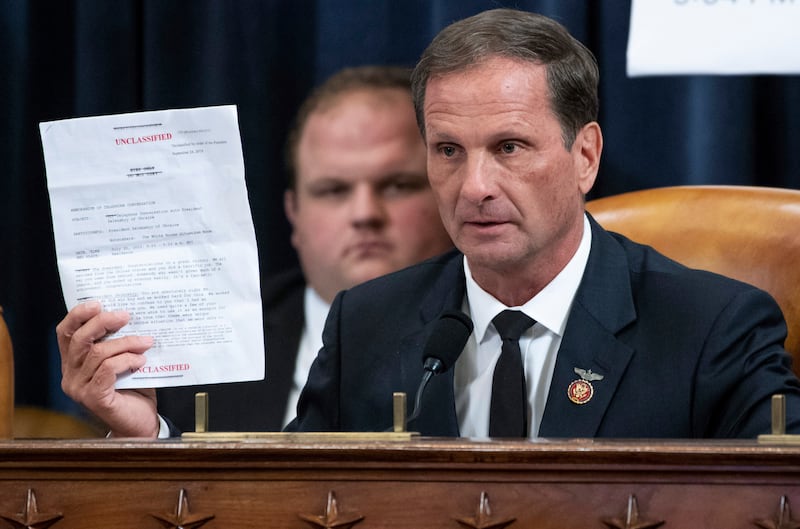

Stewart, 63, is the longest-serving representative among Utah’s four current U.S. House members, most prominently as a member of the House Intelligence Committee. First elected in 2012, he announced in July that he was resigning to stay close to his wife, Evie, who had a stroke a year ago. While he said she’s not incapacitated or paralyzed, she lost most of her vision. He said it was difficult to leave Congress in the middle of a term, but it is the right decision.

“We’re both really happy. She just needs someone to be home with her. She’s so relieved to know that I’m not going to be gone all the time,” he said.

In addition to addressing mental health issues, he championed national defense and religious rights during his tenure. His Fairness for All bill attempting to balance religious liberty and gay rights didn’t pass, but many of its provisions were folded into other bills. He voted for the Respect For Marriage Act, which codified the right to same-sex marriage in federal law, and also significantly protected religion.

“As a man of faith and a conservative, ensuring the religious liberties of people in Utah is absolutely essential. This bill not only guarantees that protection, but simultaneously expands the rights of those in the LGBTQ community,” he said in a statement at the time.

Yet big moments aren’t necessarily the total of one’s impact.

“In Congress, I don’t think there’s usually one thing that you think, ‘OK, this is my magnum opus.’ It’s really a collection of smaller bills that you hope in aggregate have a positive impact,” he said in a 2018 interview.

Stewart is backing one of his own staffers to replace him. He endorsed Celeste Maloy, the chief legal counsel in his office the past four years, in the upcoming special election. Former state lawmaker Becky Edwards and businessman Bruce Hough are also on the Republican ballot.

Why Stewart ran for Congress

A business consultant, author and former Air Force pilot before getting into politics, Stewart said he didn’t know what he would do for work when he decided to resign. He knows now, though he’s mum, other than to say he’ll be involved in the areas of national security and intelligence but it won’t require him to routinely be away from home.

A first-time candidate with no previous aspirations for elected office, Stewart entered the political arena in 2012 campaigning to lower the national debt and curb “insane” government spending. While sequestration — a law requiring across-the-board cuts in some federal spending — did slow both for a couple of years, Stewart said Congress lost focus.

“President Trump didn’t care at all about the deficit. I talked to him about that, twice actually,” he said, adding the president told him he planned to address it in his second term.

“But he’s a leveraged New York businessman. He uses debt to create things and to build things and just didn’t feel the same way about it as we did. Honestly, he was wrong on that. We should have kept on that, kept the pressure on.”

Relationship with Donald Trump

Speaking of Trump, Stewart wasn’t initially a supporter. He served as Sen. Marco Rubio’s campaign chairman in Utah during the Florida Republican’s short-lived run for president.

At one point, Stewart said Trump didn’t reflect Republican ideals and referred to him as “our Mussolini.”

“I’ve been quoted on that a lot. As soon as I said it I thought that’s going to be memorable,” he said.

Stewart said he felt he had to respond to then-candidate Trump’s saying that he would target the families of terrorists, presumably women and children, and also torture terrorists. When Trump was told that would be illegal, he responded by saying he’s such a strong leader that the military would do it because he told them to.

The congressman said he wasn’t really comparing Trump to the fascist dictator but trying to draw a contrast. He said the military is trained to know an illegal order and not to follow it.

Trump, though, apparently didn’t remember or didn’t care about the comment until it was later brought to his attention. Trump was close to nominating Stewart as national intelligence director in 2020 until he learned of a video clip in which the congressman’s Mussolini comment was shown.

Even though Stewart had developed a good relationship with and had become a staunch defender of Trump after he became president, the remark doomed his opportunity to join the Cabinet.

“Interestingly, he and I got to be quite close. Primarily because of the work we did on intel, the Russia investigation. We spent a lot of time together. We still do on occasion, not as much as we used to. We still talk and kind of touch base with each other,” Stewart said.

Trump endorsed Stewart in the 2022 election, which he won just as easily as he did his first five races.

View on Jan. 6

Stewart was all in on Trump in 2020. After the election, he said there was plenty of evidence to question the results. He was among 139 House Republicans who objected to certifying Pennsylvania’s electoral votes, though he notes had the objection passed, it wouldn’t have changed the outcome. And he said he acknowledged Joe Biden as the winner immediately after news outlets called the race for him.

But, “We had to say to Pennsylvania what you’ve done here does not comply with the Constitution, it clearly doesn’t,” Stewart said.

On Jan. 6, 2021, Stewart had a front-row view of the wild scene outside the Capitol. He said he saw 30 police officers run by inside the building and followed them to see what was going on. One ushered him into an office overlooking the patio. Protesters, he said, were banging on the window.

“Jan. 6 was a mess,” he said. “I watched the whole thing. I remember texting everyone (on his staff) that this is going to change everything.”

In the aftermath, the Democrat-led House voted to form a committee to investigate the Capitol attack and Trump’s role in it. Stewart was among a majority of Republicans who opposed it.

“The reason I opposed it was borne out by how they acted. This wasn’t a fair and bipartisan effort at all,” he said.

Looking back now, Stewart said he feels “100%” the same about those issues as he did at the time, and with hindsight even more so that his decisions were correct.

Trump indictments

One of Stewart’s last assignments was as a member of the House Subcommittee on Weaponization of the Federal Government, charged with investigating the Biden administration.

As Trump faces four separate criminal indictments, including some related to Jan. 6 and his attempts to overturn the 2020 election, Stewart said he’s “deeply concerned” that the Department of Justice, the FBI and to some extent the CIA are being weaponized as political machines.

“I’m afraid the indictments we’ve seen are an extension of that. There’s no way the country walks through this thing without enormous pain and without enormous danger. It’s going to lead to a constitutional crisis we have never seen,” Stewart said.

“I’m not a legal scholar. I’m not an attorney. But I’m also not stupid. I can look at these charges and go that makes no sense to charge this president with that charge 2 ½ years later.”

Even so, as Trump campaigns for president again, Stewart says he hasn’t chosen a presidential candidate to support in 2024.

As for himself, Stewart said he can’t imagine running for public office again.

Gathering intelligence

Stewart said he recognized the magnitude of serving in Congress on his first trip overseas to a country in the Middle East on an Air Force jet. He said stepping off and looking back at the white and blue aircraft emblazoned with United States of America made him realize the symbol that the U.S. is to the rest of the world.

“It was something kind of unique and also something powerful,” he said. “I thought this is really cool that we get this opportunity to go represent the United States to other people and other nations.”

On the Intelligence Committee, Stewart was privy to a lot of happenings in the world — some comforting, some disturbing — that he wasn’t and still isn’t free to talk about publicly.

The ability of the U.S. to gather intel on its adversaries such as knowing Russian President Vladimir Putin’s intent to invade Ukraine allowed it to prepare its allies and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy for the imminent attack, he said.

But, Stewart said, he has a long list of things that worry him, like the vulnerability of the nation’s electrical grid and what would happen if it were destroyed. He said he left some intelligence briefings wondering how the U.S. could have possibly put itself in certain unfavorable positions.

“With everything that we fix, two things that are deeply concerning pop up,” he said, adding he’s not predicting the end of the world.

Still, Stewart said he has struggled with pessimism for the future. He said he’s sought counsel from church leaders and others about being optimistic. On the other hand, he said he feels like he needs to tell people the truth.

“It’s been a challenge for me to thread that needle,” he said.

For him, it comes down to two things.

First, Stewart said, American society is resilient and the country has gotten through tough times in the past, most recently the COVID-19 pandemic.

The second thing, he said, is his belief “that God still cares about this country, and we need this country to survive. We need this country to be the global leader that, whether we like it or not, we are. Other nations still look to us for leadership. If the United States crumbles, the other nations feel it in severe ways. I think God will still help us work our way through some of these huge challenges.”