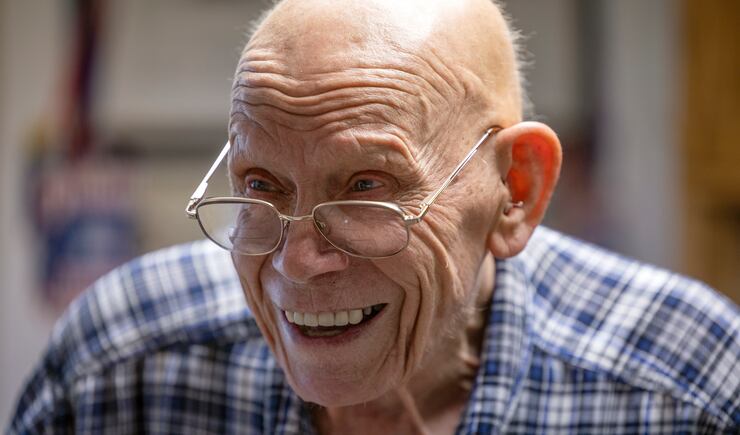

Don Pullan is quick to admit he can’t remember quite as well as he once did.

“I have good days and I have bad days,” he says with that air of what-are-you-going-to-do acceptance men tend to acquire when their next birthday will be their 98th.

But if he can’t always immediately tell you what he had for breakfast, his recall of 77 years ago is as sharp as ever.

On June 10, 1944, Cpl. Pullan, of Salt Lake City, Utah, landed on Utah Beach as part of the D-Day invasion.

He wasn’t with the first wave of troops that came ashore on June 6, when German resistance claimed some 13,000 casualties, including 4,400 dead, as the Allies sent 156,000 soldiers to mount the initial assault on Europe.

Pullan’s turn came four days later, a day before the Normandy Coast was secured and the D-Day invasion considered a success. He was part of the 911th Air Engineering Squadron, an outfit responsible for clearing wrecked planes and other war debris and pulling either the wounded or dead from the wreckage.

Utah Beach was the westernmost of the Normandy beaches and along with Omaha Beach the landing spots for U.S. troops during the invasion. The beaches got their names, so the story goes, when a few days before the invasion, Gen. Omar Bradley, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower’s right hand man, randomly asked two enlisted men where they were from. One said “Utah,” the other, “Omaha.”

Utah Beach was quiet when the landing craft Pullan was riding in stopped several hundred yards from shore. But that didn’t mean they weren’t going to get shot at, or for that matter survive the watery crossing.

“I looked at Del,” says Pullan, Del being Del Mercer, his best buddy in the outfit. “I said, ‘swim or drown?’ He said, ‘probably drown’ and we jumped in.

“I was up to about here” — he points to his chest — “then I took about 10 steps and I was here” — he points to his waist.

“From that point on we ran like crazy to get in.”

To their surprise and great relief, they heard no shots, saw no Germans unless you counted the bodies still littered on the sand.

It was so quiet, “we coulda had a dinner party there,” Pullan says.

Thus began a march through Europe — first France, then Belgium, then Holland, and finally Germany — for the 240 men of the 911th that stretched through 1944 and into the spring of 1945. The Nazis were on the run. The Blitzkrieg was going backward.

The engineering company arrived in the city of Kassel, in the middle of Germany, in early April, where they helped liberate a subcamp of the Dachau concentration camp.

It was here, as the war was nearly over, that Pullan met what he calls “my Waterloo.”

He stepped on a landmine as he was taking a picture of a farmer standing in his field. The blast damaged both legs so severely that there was a fear he might lose the right one.

Walking around his home on the east side of Salt Lake City 7 1/2 decades later, Don Pullan is living proof that didn’t happen.

“Come on,” he says, “let me show you my war room,” and he sets off with his faithful dog Lilly down a flight of a dozen steep stairs to the basement.

The room is full of battlefield relics, replicas and memorabilia, a smattering of medals, photographs — including the ones Pullan personally shot — and the heavy metal helmet Pullan wore all the way through Europe. A veritable WWII museum. In the corner is Cpl. Pullan’s Purple Heart and his Good Conduct Medal.

“I asked the guy when they were giving it to me, ‘How well do you know me?’” he quips.

“I enjoy taking people down here,” he says with obvious pride. Unlike many of his Greatest Generation peers, he says he’s always talked about where he went and what he saw.

“I found it was easier to talk about than it was to keep it inside. If you run away from it, you never accomplish anything.”

“I like to have fun and I like to laugh,” he says, listing a couple of possible reasons for why he’s made it to age 97 still independent, still living in his own house, still going strong.

As for making it through the war, “I was just awful lucky,” he says. “There were a lot of them in front of me that didn’t make it, and a lot of them behind me that didn’t make it. When those pieces of shell start flying, they don’t have anybody’s name on them, they just sail along until they catch somebody.

“And I do think the Almighty had his hand on me.”

As he holds Lilly in his lap, he laments the passage of time that has taken so many of his war buddies. “I hate to think about it,” he says. “I don’t think there’s many of us left.”

He’s right on that score. Of the 16 million G.I.s who fought in World War II, fewer than 250,000 are believed still alive, and well less than 5,000 who landed on Normandy’s beaches the invasion week of June 6-11, 1944.

The soldier from Utah has returned to Utah Beach just once, in 2006.

“I shed a lot more tears when I went back,” he says, his eyes misting anew as he thinks about Del Mercer and all the men he spent one memorable year with marching through Europe.

“We were trying to make the world free for all of us,” he says. And as Dizzy Dean once said, “It ain’t braggin’ if you done it.”