Editor’s note: Year after year, public camping and homelessness has persisted as an issue in Utah’s capital city — made even more complicated by the pandemic. The Deseret News looked to Austin, Texas, in search of both short- and long-term solutions. This is the first of a two-part series.

AUSTIN, Texas — The two settings are dramatic opposites.

One is a state-sanctioned tent city, tucked — practically hidden — away in an industrial area just north of the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport. Tents, tarps, makeshift fences made out of pallets and port-a-potties sit on a hot slab of asphalt.

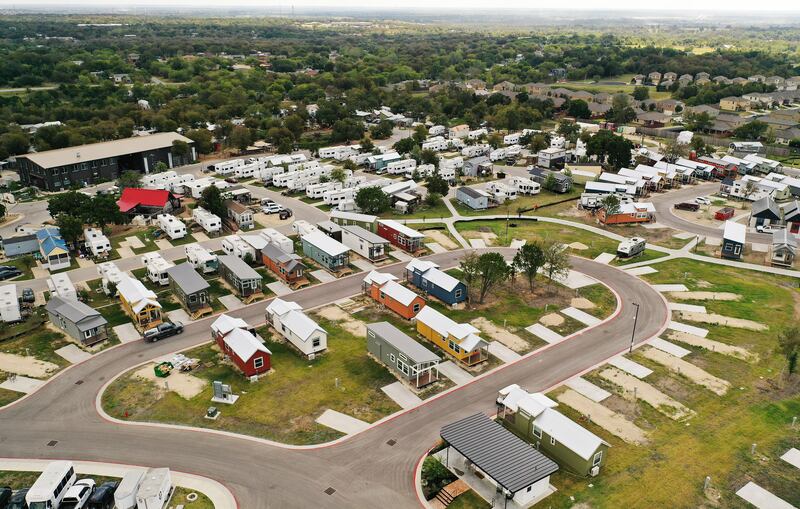

The other is a master planned tiny home village, built on the outskirts of southeast Austin. Tiny homes of all shapes and sizes line curved, paved roads and sidewalks, adorned with manicured lawns, gardens and patio areas.

The two, at least visually, couldn’t be any more different. And yet, to the people living there, they’re both seen as a solution to helping the most vulnerable: the homeless.

Whether they’re living in a tent or a tiny home, they’re proud of how they’ve made their homes — and they say they’ve found a sense of community.

In Salt Lake City, public camping continues to be a problem each year. That’s despite the tens of millions of dollars city and state leaders spent in recent years to build three brand-new homeless resource centers, which have operated at virtually maximum capacity after they opened last year.

The issue has been compounded by COVID-19, which makes shelter living even more difficult when there’s an outbreak. Utah’s homeless system has increasingly turned to hotels and motel vouchers to house the afflicted.

Tents, trash and drug use this year again amassed on streets west of the Rio Grande Depot and spilled onto grassy strips along streets, neighborhoods and parks throughout Salt Lake City.

Amid the pandemic, protests and concerns that forcing the breaking down of homeless camps could lead to a constitutional fight, Salt Lake City leaders took a gentle approach to cleaning up on-street camps this summer, instead focusing on social work and persistent outreach to provide services to the unsheltered, and often the service resistant.

Now, with winter at Salt Lake City’s doorstep, homeless advocates, and city and county officials are again scrambling to come up with another temporary winter overflow solution. It’s the same song and dance as last year — but this time amid the chaos of COVID-19. Since warehouse-style shelter settings, like last year’s Sugar House temporary winter shelter, aren’t COVID-19 friendly, they’re seeking other solutions like hotels.

Another year went by without a clear solution to on-street camping, especially for those who want to be left alone.

The Deseret News visited Austin, Texas — where the homeless population puts Salt Lake City’s problems in perspective — in search of new solutions, both short- and long-term.

The search brought the Deseret News to two dramatically different concepts: the tiny home community and a sanctioned tent city. One concept took years and has so far cost upward of $45 million to build. Another was essentially established overnight with no such major budget.

To Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall, only one is seen as an acceptable model that could or should be replicated in Utah’s capital city — a managed tiny home community.

“When I talk to people on the street who choose that lifestyle over and over, I hear, ‘This is my community, I don’t want to go to an apartment where people surrounding me ... don’t understand my needs and my struggles,’” Mendenhall said. “I get that. I think we get that need for belonging and a place, a place of permanence where you’re accepted as you are.

“And that’s what drew me to interest in managed tiny home concepts.”

‘My castle’

Bryan Coward, whose face is weathered by years of homelessness, plopped himself in a chair on his miniature porch.

This was his porch, in front of his house, filled with his belongings: a bed, a TV, cupboards filled with food, and a place to hang his Pittsburg Steelers jerseys. The micro home, not a lot more than 200 square feet, isn’t much — but it is his.

“It’s my castle,” he said. “I’m proud of it.”

Sitting in one of his patio chairs, Coward said his porch is the hangout spot — where his friends and neighbors come in the evenings to barbecue, smoke cigarettes, drink beer and listen to music after a day of work. He showed off the ashtray sitting on his little table, explaining he doesn’t like to smoke, but he accommodates the friends who do.

When his neighbor, Larry, walked by, the two shouted and waved at each other. Birds chirped from nearby trees. A rooster crowed in the distance from the neighborhood chicken farm.

This is home.

And at $360 a month, it is a home Coward said he can actually afford on his $783 a month.

“Social Security don’t get you enough money to rent a place,” he said. “$700 a month, you can’t rent no place for that, you know. I don’t care where you go, it’s not going to happen.”

It’s a stark contrast to how Coward, 53, used to live in what he guessed was seven years of homelessness after he came from Beaumont to Austin looking for “something new.” Why was he homeless? He answered simply: “My choice.”

He told of how he lived at the ARCH, the Austin Resource Center for the Homeless, one of the biggest homeless shelters in downtown Austin. He also said he’d at times camp on the streets, under freeway overpasses — like hundreds who still do.

“It’s better than being under a bridge, you know,” he said.

Now, Coward’s part of a community: a master planned, tiny home community for the chronically homeless called Community First! Village, developed by the biblically based nonprofit Mobile Loaves & Fishes.

Tiny home village

Mayors, including Mendenhall, community leaders and homelessness solution-seekers from across the U.S. have turned their attention to the quirky tiny home village — with so far 27 acres (and more coming) full of homes — from RVs, tent-like structures called “canvas-sided cottages,” to tiny homes (some of which are 3D-printed), and micro homes, which don’t have plumbing, but are situated near community kitchens, laundry, shower and restroom facilities.

The average tiny home size ranges from about 150 square feet up to about 350 square feet.

Community First! Village, which opened five years ago, currently includes about 100 RV/park homes and 130 micro homes on 27 acres. It’s now expanding to include an additional 310 tiny homes on 24 more acres next door to total 51 acres. Plans for further expansion are in the works.

The village’s visionary — real estate developer Alan Graham, who was once the scorn of Austin NIMBYs (not in my backyard) before he was awarded the prestigious Austinite of the Year Award — calls it the “most talked about neighborhood” in Texas and the nation.

“There’s no place like this. This really kind of mirrors the kind of community that we desire to live in,” Graham said. “That’s why I moved out of the fanciest neighborhood in Austin, Texas, sold my house and moved into this beautiful place.”

Graham, as he sat on his porch out front of his own tiny home, explained he used to live in West Lake Hills, “where the billionaires predominantly live.” Previously a real estate investor and developer, he joked he was on the “impoverished” end of the West Lake neighborhood, but enjoyed raising his family there. It was after he began spending more time in Community First! Village than his own home that he and his wife decided to move into the neighborhood they helped build.

Graham explained how he founded Mobile Loaves & Fishes, which began as a food truck that traveled throughout the city to feed the homeless. Years of focusing on relationships with the homeless brought Graham to become “fascinated with their resourcefulness and their resilience, and realizing that these are not bums and people who are lazy and who are choosing to live in this unbelievable abject misery.

“And now they’re just a part of my life. They’re my neighbors,” Graham said.

To be eligible to live at Community First! Village, an individual must be defined as chronically homeless — or living on the streets or in a shelter for the last year continuously or on at least four occasions in the last three years totaling at least 12 months.

“We’re talking about the most despised outcasts of our city,” Graham said. “People battling mental illness, drug addiction and physical health issues. The people that you normally see standing on our street corners and living underneath our bridges. That population.”

But walking through the village, it feels like a tight-knit neighborhood. Everyone seems to know each other’s names, and they wave and shout to each other as they pass by. As Graham talked, one of his neighbors, William, stopped by to chat. Graham, who called William “brother,” told of how William has a knack for carpentry and has crafted many of the patio tables under a pavilion next door.

The village is not just a subdivision of tiny homes and RVs. It’s a community with wrap-around social services, a marketplace, workshops where tenants can learn trades like vehicle repair, carpentry, pottery, painting, metal work. The tenants there earn their living, with jobs like gardening, mowing and landscaping.

There are chicken farms and goat farms, where eggs and goat milk are harvested for the community. There’s even a memorial for the tenants who have died — a tangible reminder that they’re part of a neighborhood that won’t forget them when they die.

The tiny homes are not free — but they’re affordable. Tenants are required to pay rent, ranging from about $230 a month to up to $440 a month, depending on the unit type.

There are three rules in Community First! Village: 1) Pay rent on time. 2) Abide by civil law and 3) Follow the rules of the village. Such rules are not unlike a homeowners association for a neighborhood.

The result is a community that has the feel of any regular neighborhood but the variety and character of a KOA campground. Graham explained the village began as a fantasy of building an “RV park on steroids.”

One of the most common questions Community First! officials get is about the presence of drugs. Their answer? There probably are some drugs, since the tenants have privacy within their homes, just like any other homeowner in a regular neighborhood. But the village’s residents are supported with wrap-around services and case management to address substance abuse.

“There’s no model in which you can force people to stop drinking or using drugs” said Amber Fogarty, president of Mobile Loaves & Fishes. “It doesn’t work in any of our families, and it doesn’t work here in this village. What people most need is a place where people are supported and cared for, and then we can begin to address those really difficult challenges together.”

Salt Lake’s foundation

In Utah’s capital, Mendenhall is one of the many mayors across the country who have eyed Community First! Village as a model they’d like to see mirrored in their home states. She told the Deseret News she and other city officials had planned a trip to visit the community, but then COVID-19 hit, and they canceled those plans.

But in her research, and through word-of-mouth from other “city nerds” and mayors across the country, Mendenhall said Community First! Village keeps coming up.

“Salt Lake City has been willing to be a creative and progressive partner in exploring new ways to address our housing needs and homelessness needs in the city, and Loaves & Fishes is a concept ... with volunteers that are inter-stitched into the fabric of the community that we’ve never even come close to trying,” Mendenhall said.

“Salt Lake City also has quite a bit of land, which could be an opportunity for us to be a real true invested partner in this kind of initiative.”

Mobile Loaves & Fishes, Graham said, has a “replication process” for communities that want to mirror its model. The three-day process is immersive, and to some is “intimidating” because of the size and scope of the village.

More than 400 people from 31 states and 130 to 150 cities have been here,” Graham said, explaining modeled communities have been built in Springfield, Missouri; Victoria, Texas; Midland, Texas; and one about to break ground in San Antonio, Texas.

But a tiny home master planned community like the one Mobile Loaves & Fishes built — after years of battling NIMBYism and only after they found a plot of land barely outside Austin’s city limits that had no existing zoning laws — was only possible because of Graham and his nonprofit’s persistence.

To Graham, there’s no quick solution to homelessness. And it takes not only a yearslong commitment to pull off something like Community First! Village, but major philanthropic commitments.

Government, he said, should only play a “subsidiary” role.

“When you look at where we are today, it’s taken us two generations to get here,” Graham said. “That’s 40 years to get where we are today. And people want it fixed tomorrow? Stop. It’s not going to happen.”

Graham said it will take political courage and committed partners — but he believes Salt Lake City has the cultural foundation to make it happen.

“You know what’s interesting about Salt Lake City? This is a stereotype, I’ll admit it, but Mormonism. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Mormons that we’re connected with here are some of the most family-oriented, powerful, compassionate people that I’ve ever met. It seems like Salt Lake City’s got a foundation that could be very different.”

Mendenhall said she doesn’t know yet who that crucial partner might be in Salt Lake City, but she acknowledged Utah’s faith-based culture of charity and service — from many different nonprofits and faith organizations — indicates there will be willing partners.

“What we’ve seen in Salt Lake City year after year is an increase in compassion, I believe, by our housed population for unhoused residents here,” Mendenhall said. “People want to help. And Utah has the highest amount of volunteers in the country.

“It doesn’t mean there won’t be challenges to it, but I think we have the right political makeup, community appetite and social interest and demand right now — with higher homelessness numbers than we’ve probably ever seen in the state’s history, to do something different. And be able to do it well. And to do it well means we need partners.”

Lessons learned

What can Salt Lake City learn from Austin?

By no means has Austin “solved” its homeless problem, with large tent encampments packed under freeway overpasses and lining main thoroughfares into its downtown. But innovative solutions have taken shape there — like Community First! Village.

Numbers-wise, Utah’s and Salt Lake City’s homeless population pales in comparison to the giant state of Texas, where statewide, more than 25,800 people have been tracked experiencing homelessness on a given night in 2019, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness. In Travis County, where Austin is located, about 2,255 people experienced homelessness on a given night in 2019.

In the entire state of Utah, 2,798 people were experiencing homelessness on a given night in 2019, including in shelters and on the streets. In January of this year, Utah’s Point-in-Time count tally increased by about 12% to 3,131.

Austin alone is about the size of all of Salt Lake County, where the bulk of Utah’s homeless population has been tracked. There, about 1,844 people experiencing homelessness have been tracked on a given night in 2019.

But those numbers came before the pandemic hit. Homeless advocates have been seeing a spike in need for homeless services as the pandemic has roiled the economy and complicated day-to-day life.

In Salt Lake County, Volunteers of America-Utah outreach teams report seeing an increase of individuals camping on the streets, completely new to homelessness. They estimate there have been about 130 completely new homeless clients enrolled in the state’s homeless system between March and June of this year. Last year, during the same time frame, Volunteers of America enrolled about 50 new clients.

If Salt Lake City wants to replicate, on any scale, a tiny home village, it would require an enormous lift from Salt Lake City government leaders — including what’s likely to be rezoning and “not in my backyard” battles. Not to mention, government can’t do it alone. It’s no short-term solution.

So even if a private partner with the wherewithal and the commitment shared the same vision of a tiny home community as Mendenhall and other Salt Lake leaders, it could take years to pull off.

Mendenhall, when asked what the timeline could be, said it is “too soon to say” because she wants to have a robust public process. But Mendenhall said “even just saying the words ‘tiny home community’ as mayor of Salt Lake City has brought tiny home manufacturers to our door knocking like you won’t believe” with companies saying they could get houses built in 60 days.

“But we want to explore this process,” Mendenhall said. “We want to explore it with the community and do it in a thorough and productive way so that if we have the opportunity to do a pilot project, it has the potential and stability to develop into a permanent solution.”

Zoning, alone, would be a beast all its own. Wherever any Salt Lake tiny home community might be built, Mendenhall expects NIMBY-ism.

“I was on the council when we sited the homeless resource centers, so of course I do expect community feedback wherever it would go,” she said.

Salt Lake City Councilman Chris Wharton said zoning changes “always have the potential to be controversial.” But as long as there’s a thorough public process, he said the City Council “definitely has an interest in all types of innovative solutions” to homelessness.

They question is — if a Salt Lake City tiny home village is ever built — what happens in the meantime?

Next: A look at Austin’s state-sanctioned camping area for the homeless and the cases for and against such a community in Salt Lake City.