SALT LAKE CITY — Nearly two years into Utah's Justice Reinvestment Initiative — the ambitious reform aimed at curbing the steady march of drug offenders to the state prison by offering treatment instead — policymakers and prosecutors remain divided on whether the law is working.

On one side, the state's Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice affirms that reclassifying some drug offenses from low-level felonies to misdemeanors has had no negative impact on public safety.

On the other, officers patrolling Salt Lake City's exploding downtown drug market and prosecutors trying to litigate stacks of new low-level cases say that because accompanying resources went initially unfunded, the JRI reforms have brought chaos to the criminal justice system.

A new study commissioned by the Utah Association of Counties in response to frustrations over the reform has found that most crimes are down statewide, while those that are trending upward — such as thefts from motor vehicles — were already climbing before the new law took effect in October 2015.

Utah Association of Counties, July 2017 | Aaron Thorup, Utah Association of Counties, July 2017

Despite the findings, police and prosecutors remain adamant that decriminalization of drug crimes without treatment options to fill the gap is putting pressure on the courts, county jails and communities.

"Down to a person my felony prosecutors will tell you that they have seen a noticeable push into the county jail and into the community of people who they consider high risk to the community, and the sentences are much softer," said Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill.

Ben McAdams, Salt Lake County mayor, said he believes the analysis is just the beginning of what needs to be a hard look at the justice reform efforts.

"I think JRI has been a major shock to the system, and the impacts of that are phasing in over time," McAdams said. "Because I think JRI was poorly implemented, we're seeing our communities are less safe, and the individuals who were formerly warehoused in the prison are now on our streets and making our communities less safe."

Faced with feedback from frustrated prosecutors and police officers fighting Utah's drug war, Adam Trupp, CEO of the Utah Association of Counties, said the association set out to learn more about what was happening in the trenches. The Sorenson Impact Center was hired to do a detailed data analysis to flesh out those concerns.

"No study is a complete answer. But at this point, I don't think the data is demonstrating that things are falling apart," Trupp said.

Daniel Hadley, chief data scientist for the Sorenson Impact Center and the lead researcher for the report, said the study's findings don't show signs that any escalation in crime can be attributed to the reforms but emphasized that no one study can offer definitive answers, and it is too early to say for sure what effects, if any, the Justice Reinvestment Initiative has had on public safety.

"There is no inflection point that would tie these trends to the Justice Reinvestment act," Hadley said.

However, according to Jeff Buhman, Utah County attorney, the study also lacks any sign that JRI reforms are beginning to have a positive impact.

Buhman said that when the Justice Reinvestment Initiative became law, the majority of prosecutors under him were supportive of the reform, recognizing the need to replace incarceration with treatment for those offenders who could turn their lives around.

"We thought there needed to be more resources put into the system for treatment. You know, we're not here just to put people in jail or prison, we want people to not recidivate. It's good for them, it's good for us, it's good for communities," Buhman said.

But while the reforms passed, Medicaid expansion that would have funded substance abuse and mental health treatment didn't, leaving the justice system without the resources it had anticipated. Now, the Legislature is attempting to make up for the funding gap that is believed to exceed $16 million, this year allocating $6 million across the state for substance abuse intervention and treatment.

While there are indeed fewer people in the Utah State Prison since the reforms were adopted, Buhman said there is still no evidence they are breaking cycles of criminal behavior.

"It depends on your perspective. If improvement is fewer people in the prison, then JRI has been successful. But to us it has to be both — fewer people in prison, and things like the crime rate and recidivism, they need to go down," Buhman said.

Buhman said that if the goal of the initiative is actually to simply save money by putting fewer people in prison, it's likely a success.

"But nobody sold it that way," Buhman said.

Ron Gordon, the executive director of the Utah Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice, said the goal was to reduce recidivism, and that it's too soon to tell whether that's happened.

"My office never said the goal was to get people out of prison. That was not one of the stated goals. Nor was it to save money. The goal is to improve public safety by reducing recidivism. One way to do that is to make sure that lower risk individuals are not sent to prison, because we know that prison increases the odds that people will commit crimes in the future," Gordon said.

The key, Gordon argues, is that excessive use of prison for low-level crimes actually serves to harden low-risk offenders.

"And that," he said, "actually makes us less safe."

Gordon said that McAdams has declined invitations to meet to discuss the initiative.

"We've asked to meet with him so we can better understand why he is saying things that do not appear to be supported by any data at all. We want to fix a problem if it exists. But so far, the criticisms he is leveling at JRI are not based on data," Gordon said.

Drilling down

Those who solicited the study from the Sorenson Center are leery about accepting its results just yet.

Scott Sweat, Wasatch County attorney and chairman of the Utah County and District Attorneys Association, said that while the group has received updates about the study along the way, it has not yet received a final report.

"We are trying to get accurate information," Sweat said. "We don't want to rely on anecdotes. We are just trying to monitor what is going on."

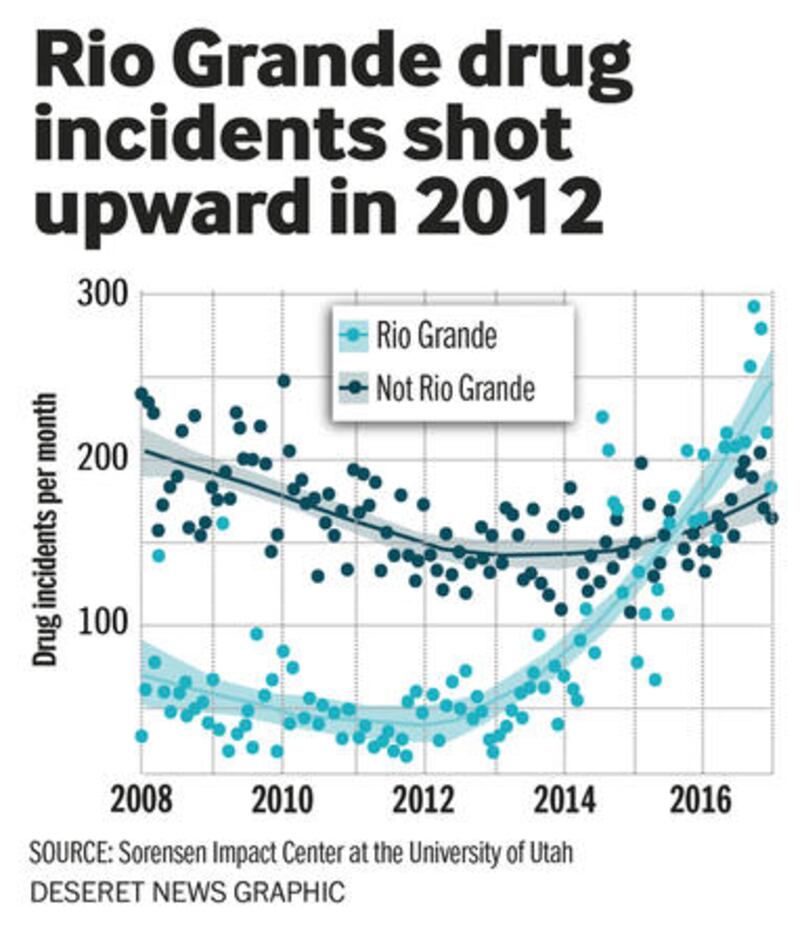

While other crimes have remained flat or ticked down statewide over the past several years, drug crimes are on the rise, pushed upward by a spike in Salt Lake City's embattled Rio Grande neighborhood, the center of the city's homeless population.

Rio Grande drug incidents shot upward in 2012 | Mary Archbold, Sorensen Impact Center at the University of Utah

Drilling down into Salt Lake City's statistics, the Sorenson study finds that the trend began before 2013, two years before Justice Reinvestment Initiative was put in place.

But even the best data can never give all the answers, Hadley said. He notes that it is impossible to separate changes in enforcement policy from actual crime, and the spike in the Rio Grande area could possibly be a combination of the two.

Gill said the study confirms that Salt Lake City is the epicenter of Utah drug crime and thus must receive the bulk of available resources to make the reform work.

"Salt Lake has the volume, the need and the biggest impact on the system as a whole," Gill said. "Our success will be the state's success, and our failure a state failure."

The Sorenson study also revealed a sharp increase in the number of fugitives from parole or probation. Those numbers did jump upward in late 2014, corresponding to a shift in the state's prison release and parole policy that was tied to the justice reinvestment effort.

Officials at the Department of Corrections were initially caught off guard when the fugitive numbers became public earlier this month, and struggled to explain them. They suggested that some of the increase stems from new policies that hold a tighter rein on parolees, leading to warrants being issued that might not have been previously.

"I'm not buying that," Gill said.

Gill, meanwhile, had no ready answer for why a spike in fugitives does not seem to have created a corresponding spike in crime.

While the results of the study didn't demonstrate an uptick in crime that beleaguered cops and attorneys seemed to think they would find, all stakeholders agree that more time and better data must be allowed to accurately assess and put evidence behind the next steps for JRI.

McAdams said he is encouraged at the effort to put hard numbers behind "what we're seeing on the ground." But because the Sorenson study measures only up until November 2016, while the problems he sees have kept growing in the interim, he is reluctant to accept it as a comprehensive illustration of what's happening.

"I think some of what I see also was a real need for more data and more current data," McAdams said. "I think the data is always an incredible tool for helping us to diagnose the strengths and weaknesses of our system and how we can improve it, and it would be useful to have more data and more current data on some of these challenges."

Better and faster

Many stakeholders share the frustration with slow and clunky data that drove the counties to commission the Sorenson study.

For years, Rep. Eric Hutchings, R-Kearns, the chief House sponsor of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative in 2015, said he would ask people working in the corrections system what they needed to do their job better.

"They would always say, 'We need lots of money to do lots of great things for lots of people,'" Hutchings said.

Hutchings sees the Justice Reinvestment Initiative, at its core, being about collecting better data to make better justice policy. Without investing in data, Hutchings said, the state will never know if it is pouring its treatment and supervision dollars down a rat hole.

While the Utah Association of Counties paid for the study from its own coffers, earlier this year it persuaded the Legislature to appropriate $2 million to start building software needed to modernize the state's crime and justice statistics.

Among those helping to frame Utah's new crime data effort is Steve Cuthbert at the Office of Management and Budget in Utah's Governor's Office. Cuthbert said his task is to help ensure that whatever system gets built serves Utah's most pressing justice system needs.

"This is a lot of money," Cuthbert said, "we want to make sure that we know exactly what we want to accomplish before we start building the technology."

Cuthbert said his mandate is, first, to get good information flowing to and from individual cases, then to make sure all that data is collected to drive better policy. It's a loop, moving from the individual to the data set and then back to the ground level.

"You could go out and build a big software solution," Cuthbert said, "but if people on the ground aren't using it to make decisions then there is no point in expanding it."

Key decision points include the arrest, when charges are filed, pretrial handling, sentencing, post-conviction treatment plans, and then re-entry pathways.

For now, Cuthbert said, the group is focusing on organizing data to improve sentencing decisions, which he calls a "triage point" that determines whether someone "deepens" into the corrections system or begins to dig out.

Those working on the software hope to have a prototype ready by September, Cuthbert said.

Real time

Utah's criminal justice reform stakeholders all insist that policy changes going forward must be driven by reliable data, not by emotion fueled by individual crimes or cases.

But in a world of instant financial data and transactions, legislators and other policymakers are waiting 15 months for the data needed to drive policy adjustments.

Utah's Bureau of Criminal Identification reviews crime data from local police departments, forwarding those reports the to FBI, where they are checked again and then returned. The process is slow. Therefore, the state's final crime report for 2016 will not be released until March 2018.

"Every data set is going to have errors and little glitches that can show a trend that is not there," said Hadley. "The last thing any state wants is to report their data to the FBI and then discover they made a minor error that changes everything."

It's is a nationwide problem. But why does data validation have to be so slow?

"There is a huge delay once the year is over getting that data published," said Joe Killpack, field services supervisor at the Bureau of Criminal Identification. "There is always that hang-up, and it's kind of confusing why that is."

One problem, Killpack said, is that many law enforcement agencies use different software systems. Another is that there is no state mandate to collect and sift the data, so many cities are doing it in their spare time while facing other pressures.

In fact, a lack of data-crunching staff seems to be a problem from top to bottom. Multiple sources confirmed off the record that the Utah Department of Corrections is severely understaffed in this regard, leading to extremely slow response times on data requests, as well as a lack of firepower in interpreting results.

With the right resources and technology, faster data is certainly possible.

Many cities now offer data with graphs and heat maps in close to real time, with a delay of a week or less, making the information much more useful to citizens and policymakers.

All this data is displayed using the Open Data system powered by Socrata, a Seattle-based company that has contracts with more than 1,200 local governments, according to Kevin Merritt, the company's founder and CEO.

Each local government decides what data it will share on its Socrata Open Data portal, Merritt said.

Dallas has a map showing 2017 burglary hot spots. Chicago's map shows all crimes in 2017 drilling down the precinct and block level. And Los Angeles County has multiple maps, including one showing violent crime hot spots in 2017. Salt Lake shows block-level crime in close to real time.

The state of Utah is also among Socrata's clients, as well as both Salt Lake City and County.

Getting data wrong can cause panic and confusion on the streets and in the state houses. To address this risk, Merritt said Socrata has an internal approval systems that can push raw results through a chain of command, flagging possible data entry errors or duplicates, still in close to real time.

Merritt also noted that many police departments are beefing up their data analysis and communications teams, emphasizing communicating with the public about data. Some departments will, he said, not only flag a new burglary hotspot, but also share what the department is doing about it with citizens — turning the crime heat map into an interactive community blog, and citizens into active collaborators.