Decades ago Pulitzer Prize-winning author Alice Walker wrote these words that have stayed with me through the years: “No one is exempt from the possibility of a conscious connection to All That Is. Not the poor. Not the suffering. Not the writer sitting in the open field.”

We’re at a moment in history when many Americans doubt Walker’s confidence in human possibility. Americans on all sides of our divides question the dignity of those on the “other” side and even rail against the possibility that they are worth the effort. Opinion polls suggest a majority of us believe that we can overcome our hostility to one another, but a majority also believe that there are some who are just too far gone.

I hear this all the time: “Those people are hopeless. I can’t have anything to do with them.” The labels flow: They’re “contemptible,” “disgusting,” “racist,” “socialist,” “godless,” “hateful” or all of the above. With this way of seeing, those on the “other” side are exempt from “the possibility of a conscious connection to All That Is.” They’re too far gone.

I side with Alice Walker. I don’t think everyone has a conscious connection to all that is, but I do agree with her that no one is exempt from the possibility. I think the majority of us are struggling and feeling unfairly judged by the “other side.” I think the hostility that we levy against others is often hiding the pain and hunger within ourselves. I think the wounds of injustice left unchanged for generations have intensified righteous anger. But when anger becomes hatred, divisions intensify and the threats become more virulent.

Things are not as they should be — on that we can all agree. But what’s driving our search for a more just and joyful future can’t be revenge; it has to be our shared search for connection. It’s all about connection. It’s connection that we hunger to have but which we are unwittingly damaging over and over again. And it’s connection to a purpose larger than ourselves that will ultimately help us create a new spirit of us. Contempt is exactly the wrong way to find it.

Whatever your politics, I hope and believe we can dedicate ourselves to the work of connection — not just a connection to the people we like, the ideas we were raised with or the ideology we claim to be our own. Not just a connection to our team or our tribe, or to winning and defending our side. Instead, what about an effort to reach out across a divide and join with someone from the “other” side in the work of connection?

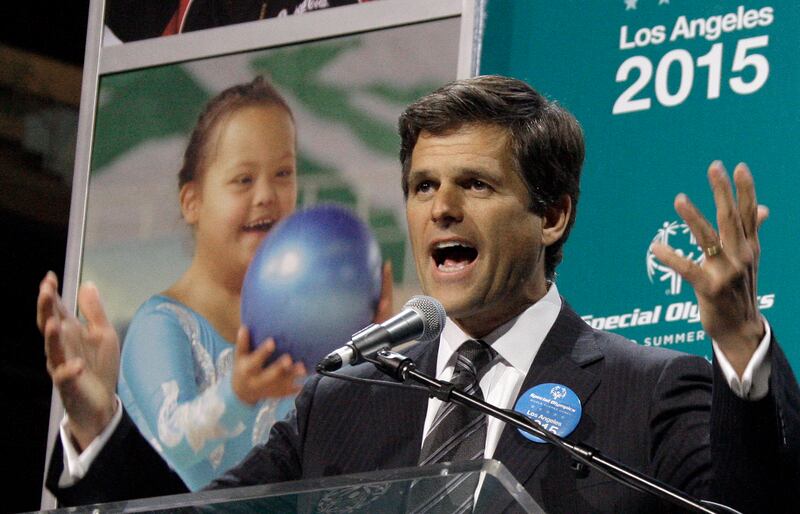

Some may find it in nature — I know I often do — simply by marveling at the miracle of a single leaf, the rounded bushy tail of a squirrel or the transcendent complexity of the human eye. Some may find it in prayer and worship, and there too, I often find an experience of “all that is” through the wondrous complexity of silence, the powerful longing of song, the companionship of prayer. I think of millions of moments I’ve experienced in my work with Special Olympics, when I’ve been in the presence of Special Olympics athletes who reminded me, with their raw and audacious goodness, that we are connected.

Is this politics? To be linked to all that is? You bet. In my view, the least important part of politics is party and elections, and the most important part is the bonds politics can form, the dreams it can inspire and the collective purpose it creates. The most urgently needed policy changes, in the end, will only happen if we, the people, are committed to each other and the possibility of fulfilling a purpose larger than any one person. All of this depends on a singular conviction: That everyone is capable of a connection to “All That Is” and the purpose of our politics is to make it possible for each of us to achieve it.

To follow Alice Walker, for me, is to be filled with hope in the moment of great changes we’re living right now. It’s true — many Americans are suffering deeply and many are suffering unjustly. And many are choosing contempt. But their pain should not obscure the hidden hope of something new emerging. We can join together — not as Democrats or Republicans, not as heartland or coastland, not as conservative or liberal — but as people capable of a conscious connection to each other and to all that is.

That’s what could change our politics. In fact, it may be the only thing that can.

Timothy Shriver is the chairman of Special Olympics International and the founder of UNITE, a mission to fulfill the promise of America through stories, solutions and studies that bring us closer together.

This story appears in the June issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.