The United States became a railroad superpower on May 10, 1869, when the ceremonial “golden spike” completed the first transcontinental railroad in Promontory, Utah. Funded with $64 million in federal loans and untold land grants, this new infrastructure linked California to the eastern states and opened up the landlocked interior for travel and trade. Trains became more than a symbol of prosperity and strength — until the automobile took over. Now the promise of high-speed rail could be changing that, starting in the Southwest. On the 155th anniversary of the project that started it all, we break down the state of railroads today and in the future.

186 MPH

This top speed will allow Brightline West — the country’s first true high-speed railroad line, projected to connect Los Angeles and Las Vegas in time for the 2028 Summer Olympics — to cover 218 miles in just over two hours. This all-electric alternative for 3.5 million air travelers and 11 million drivers each year is expected to create 35,000 jobs and ease traffic on adjacent I-15, currently a 4-12 hour drive depending on traffic. For comparison, China’s Shanghai Transrapid magnetic levitation train hits 267 mph.

8 miles … or bust

Before racing a stagecoach in 1830, the Tom Thumb was a prototype steam locomotive built to convince investors. Funicular railways and horse-drawn railcars had been in use since about 1795, but this engine’s performance — hitting 15 mph before breaking down midrace — won over the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which used the technology on the country’s first commercial line, a 13-mile commute for industrial workers at Ellicott’s Mills outside the city.

More than 1,000 dead

In the 1800s, the cost of building could sometimes be measured in casualties, like this estimate of losses among Chinese laborers on the 690-mile Central Pacific line east from Sacramento. They used nitroglycerin to blast their way across the Sierra Nevada through granite, snow and ice. Avalanches and brutal weather — 44 winter storms in 1866 and parched Great Basin summers — made matters worse. They persisted despite discrimination, low wages and poor living conditions, forming 90 percent of work crews.

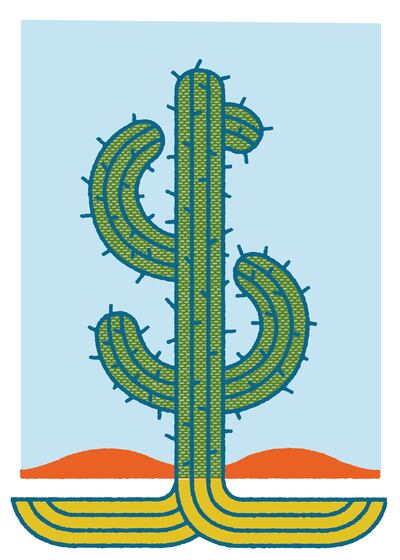

$100 billion

The current cost forecast for the 171-mile Central Valley project linking Bakersfield and Merced, California is triple the original 2008 estimate. This segment, part of a statewide high-speed rail project, will serve 6 million people in a region known for agriculture. It’s expected to launch in 2031, 11 years late. For comparison, the price tag for Brightline West is estimated at $12 billion, half of that in federal funding that has already been announced. It’s backed by finance billionaire Wes Edens, owner of the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks.

254,000 miles

American railroads peaked at this length in 1917, before the impacts of nationalization during World War I and a shift in federal funding from trains to automobiles. From 1929 to 1965, the number of passenger trains in service fell by 85 percent. Today, the national highway system is 164,000 miles long, compared to 137,000 miles of rail. That reflects the relative portions of federal transportation and infrastructure spending in 2023 — 22 percent on rail and mass transit and 44 percent on highway transportation.

28.6 million

That’s how many passengers Amtrak carries each year, including 3 million on its flagship Acela line that runs 457 miles between Boston and Washington, D.C. The country’s fastest train, it only reaches its top speed of 150 mph on a 16-mile stretch in New Jersey; another 33.9 miles of high-speed rail are sprinkled along the route. New train sets with enhanced “active tilt” systems can travel curved sections faster.

8x more efficient

High-speed rail far outpaces airplanes in terms of energy use; it’s also four times more efficient than automobiles. All high-speed trains require electrified track — currently amounting to around 1,100 miles nationwide — but Brightline West will be all-electric, and promises to run entirely on renewable energy with zero greenhouse gas emissions back to the source. It’s expected to cut 400,000 tons of carbon emissions each year.

25,000 miles

Covering this distance, China’s high-speed rail network is the world leader, with 6,000 more miles under construction. Spain and Japan are a distant second, with 1,800 miles each. The latter is a leader in velocity, expected to debut a 374 mph magnetic levitation train on the Tokyo-Osaka line in 2037. But about a dozen high-speed trains are in planning stages across the U.S., in corridors like Dallas-to-Houston and Portland-to-Vancouver, where the Cascadia is projected to add $355 billion in economic activity over the next 20 years.

This story appears in the May 2024 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.