The teen mental health crisis raging, there’s another potential answer for what might be causing so many young people to be depressed and anxious. This answer is new and counterintuitive: psychological therapy.

In other words, what we thought was the cure is actually the cause.

The theory is laid out in a new book whose title sums up its central premise: “Bad Therapy.” The book, written by journalist Abigail Shrier, has clearly touched a nerve: At one point it was the No. 1 selling book on Amazon.

Much of the book resonated with me as a culture researcher and as a parent. However, some of the book’s arguments fell flat, or were not supported by the research evidence. I’ll start with the conclusions I think are questionable, and will then move on to what I think the book gets right.

1

More teens are severely depressed and therapy works

Shrier argues that most teens who are depressed or anxious don’t need therapy. Instead, they need their parents to set better boundaries and stop focusing on their feelings so much.

In an author’s note at the beginning of the book, Shrier writes that her book is not about teens who suffer “from profound mental illness. Disorders that, at their untreated worst, preclude productive work or stable relationships and exile the afflicted from the locus of normal life. … These precious kids require medication and the care of psychiatrists.”

The problem is these types of severe problems are no longer rare. One example is a major depressive episode with severe role impairment. That means a teen fits the diagnostic criteria for major depression and that the disorder is severely interfering with school, work, social life, chores at home and/or relationships with family. That hews fairly close to Shrier’s words (“Disorders that, at their untreated worst, preclude productive work or stable relationships”).

In recent years, more than 1 in 5 adolescent girls in the U.S. fit criteria for major depressive episode with severe role impairment, nearly triple the rate of 2011. One in 14 boys also experienced major depression with severe impairment, twice as many as in 2011 (see Figure 1).

Presumably we can all agree that teens with severe role impairment need therapy and/or medication. Are they getting it?

Only about half are: In my analysis of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health dataset, 48 percent of adolescents with major depressive episode with severe impairment received either therapy or medication in 2020-2022. You can probably guess who was more likely to get it (higher-income teens, at 51 percent) and who wasn’t (lower-income teens, 44 percent). The group with the lowest percentage getting help were middle-income teens, at 41 percent — presumably because they fall into a “doughnut hole” of making too much to get government services like Medicaid but not enough to afford therapy.

On average, therapy works: Depressed people who receive psychological therapy or antidepressant medication improve more and faster than those who don’t. Shrier is correct that improvements with therapy are not as large for teens as they are for adults. Still, depressed teens who do not get therapy are twice as likely to get significantly worse than those who do.

I’m also not so sure that putting a child in therapy gives the child the message that the parent thinks “there’s something wrong with her,” as Shrier writes. It might send the message that the parent is paying enough attention to know that they are struggling. That’s a lot more than many teens get.

This is a general issue with the book, which is clearly aimed at parents who are middle-class and up and who pay a lot of attention to their kids. A sizable chunk of teens who are unhappy, depressed and lonely got that way partially because their parents ignore them or are too busy working two or three jobs to talk to them much. Too much attention isn’t the only parenting problem out there.

I agree we can do a better job as parents and as a society preparing our teens for adulthood. Having teens do more out in the physical world and focus on their feelings less is a plausible pathway for many. Still, I fear that for some parents, policymakers and educators, the message will be read as: Therapy is bad. We need less of it.

But for clinically depressed teens, especially those with severe role impairment, we need more therapy, not less. We also need more research and thinking about how to make therapy more effective for teens or find other types of interventions that can help. But suggesting they “shake it off” (as Shrier’s book suggests in its conclusion) is probably not the best approach.

2

Emotional difficulties are a spectrum, not two distinct categories

“Talk of a ‘youth mental health crisis’ often conflates two distinct groups of young people,” Shrier writes. The first is the teens with severe issues. Then there is “a second, far larger cohort: the worriers; the fearful; the lonely, lost, and sad. We tend not to call their problem ‘mental illness’ but nor would we say they are thriving.”

This draws a bright line between teens who are lonely, worried or sad and those who have major depression. However, these are not two completely distinct categories of people.

Emotional tendencies exist on a spectrum. Some people are more prone to anxiety than others, and among some that rises to the level of a disorder (such as generalized anxiety disorder). The character of the feelings are not that different; the primary difference is how much the anxiety interferes with normal life. Not surprisingly, people who are above average in anxiety are also more likely to have an anxiety disorder at some point in their lives. They then might get better, only to experience an anxiety disorder again later. The line is fuzzy, and people cross it all the time.

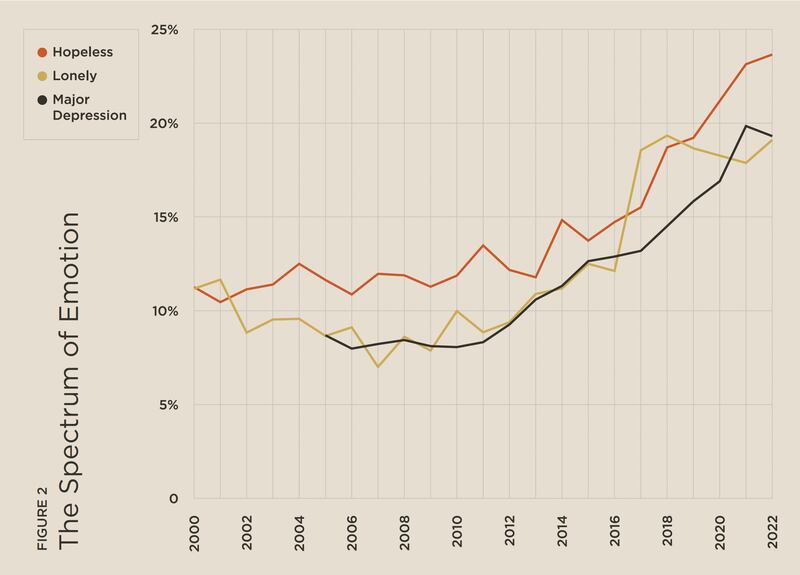

Plus, teens’ feelings of loneliness and hopelessness have increased in lockstep with more severe issues such as a major depressive episode (assessed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria). The number of teens who agree they feel lonely is actually fairly similar to the number who suffered from major depression in the last year, as is the number who agreed or mostly agreed that they felt the future was hopeless (see Figure 2). These are from different surveys of different teens, so we don’t know if all the lonely or hopeless teens are also depressed and vice versa. But this suggests to me there is not a stark division between the lonely and hopeless teens on the one side and the clinically depressed on the other, as Shrier writes.

3

Gen X teens didn’t exactly have the best outcomes

Shrier’s overall argument is that Gen X parents should be raising their kids the way they were raised — with less technology, more freedom and independence, and less parental involvement. I’m in agreement with the part about less technology; the smartphone and social media era lines up perfectly with the rise of teen depression, and social media use among teens is now so high (five hours a day, according to Gallup) that it hardly seems controversial to suggest some cutting back.

But we can’t sugarcoat the past. The Gen X adolescence had lots of great things like driving around with your friends away from your parents’ watchful eyes and learning to navigate the world independently. But that freedom had downsides: high rates of teen pregnancy and homicide. Both of these reached all-time peaks in the late 1980s or early 1990s, the prime years of the Gen X adolescence (see, for example, the Gen X chapter of “Generations”). Twentieth-century parents’ benign neglect wasn’t always so benign.

We don’t have stats on depression comparable to today’s data going back to Gen Xers’ teen years, but by most indicators Gen X was not in robust mental health during their adolescence. More said they were unhappy than boomer teens did, and teen suicide rates spiked to very high levels in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In adulthood, Gen Xers’ depression rates are about the same as boomers’ at the same age, sometimes a little lower — but that’s not a high recommendation given that boomers were considerably more depressed than the generations before them. The Gen X experience was far from ideal for mental health, especially during the teen years.

4

Growing up slowly is not all bad

The subtitle of “Bad Therapy” is “Why the Kids Aren’t Growing Up.” Shrier argues that teens are not taking on adult tasks like driving and dating because they have been emotionally stunted by their over-involved parents. But these trends are just a small part of a bigger one: Because modern citizens live longer and more education is necessary to succeed, the entire life trajectory has slowed from infancy to old age. Psychologists call it a slow life strategy. Children and teens are less independent, young adults marry and have children later and settle into careers later, middle-aged people look and feel younger than their parents or grandparents did at the same age, and older people enjoy more years of good health.

As these examples show, these changes are not all negative. Yes, teens are less independent and often don’t get enough experience making decisions on their own before they go to college or enter the workplace. But teens are also less likely to drink alcohol and have sex. In the early 1990s, the majority of eighth graders — 13 and 14 years old — had already tried alcohol. Now it’s about 1 in 4. Suddenly today’s parents don’t seem like they’re doing such a bad job.

What ties these trends together — less driving, less drinking alcohol, less dating, less sex — isn’t how good or bad the trends are. It’s that teens are simply taking longer to do adult things. Their parents are also taking longer to give up their skinny jeans and ironic T-shirts because they don’t feel old yet. Everyone’s life trajectory has slowed down, and that’s not necessarily bad.

All of that said, the book does make many good points that parents should be aware of — with a few important qualifications.

1

Kids need parents to set boundaries

Shrier argues that parenting has become more permissive, with a dose of helicopter thrown in. Many parents now focus on their kids’ feelings and do everything they can to minimize discomfort and sometimes even challenge.

It’s clear that parents are less likely to act as authority figures today and that they are less likely to prohibit children from expressing anger toward them. As Shrier correctly notes, the best parenting style is not authoritarian (the old-school “follow my rules or else” model) or permissive, but authoritative — a loving parent who sets clear boundaries. Even the middle-ground authoritative style seems to be more rare today as permissive parents favor wanting their kids to be happy all the time.

Shrier also notes the recent emergence of so-called “gentle parenting” that refuses to use any kind of consequence even for behavior like the child hitting the parent. We don’t have good data on how common “gentle parenting” is now, but it’s certainly been widely discussed online lately. Shrier is right that we should question this idea. One of the bedrock findings of psychology is that behavior modification (rewards for good behavior and punishment for bad behavior) works, especially when focused on deprivation of experiences rather than physical punishment. That means consequences like timeout for younger kids and taking away privileges (TV time, car keys) for older ones. Kids and teens do best when parents set clear expectations for behavior and enforce them.

However, that should not — as Shrier argues — mean a return to spanking, which effectively says, “Let’s teach kids that hitting each other is wrong by hitting them!” It doesn’t work. Decades of research show spanking leads to defiance, not cooperation, and is bad for kids in the long run.

Also true: Parents don’t have to give in to their kids’ feelings all the time. Children need parents who don’t cave when a 10-year-old says they don’t want to put away their laundry (because, as a mom, I don’t want to put away my own laundry either — but we all have responsibilities and kids need to learn that). Teens need parents who trust them to do things on their own (turning in homework, making a doctor’s appointment, figuring out their class schedule), even if this means facing their fears or failing every once in a while. I agree with Shrier that in trying to protect our kids we can leave them unprepared for adulthood. My own kids, now all adolescents, have benefited greatly from the experiences they have had on their own: flying alone, going to sleepaway camp, finding their own way to school.

2

Applying therapy techniques to everyone can backfire

Here’s one place where Shrier’s counterintuitive take is right on: Trying to administer mental health interventions to all teens, regardless of whether they need it, can backfire. Researchers in Australia tried this, teaching 12- to 14-year-olds skills sometimes taught in therapy such as mindfulness, reappraisal and acceptance and asking them to do homework assignments to build these skills. They thought these students would do better than an untreated control group. Instead, they got worse — they reported more anxiety and depression after participating in the program than they had before it.

For the average teen who’s reasonably happy, thinking too much about their emotions might lead them to focus too much on their negative feelings. Just as it wasn’t the best idea to try to boost kids’ self-esteem when most already felt just fine about themselves, trying to teach therapy techniques to all teens might not be a good idea.

If we’re going to try to prevent depression among teens before it starts, we could instead consider teaching them what we know works: Get enough sleep, go outside, exercise and spend time with people in person. A great blueprint for these types of lifestyle changes is in the book “The Depression Cure.”

3

The best cure for fear is experience

Shrier notes that many parents shield their children from experiences that may be risky (either physically or emotionally), thinking that this is compassionate. Many kids and teens do seem to be afraid to do things their parents regularly did as children, like walk home from school, ride their bikes with their friends or even call someone on the phone.

Fortunately, fears and phobias are among the most easily treated of all psychological ailments — in fact, they can often be effectively cured in one session. In less severe cases, they can be treated by slowly easing toward and then doing what you’re afraid of. You do it, you don’t die, and then you’re less scared of it. Our kids and teens need to know this is how our brains work.

4

Phones and social media are not real life

Shrier and I agree that today’s parents have overprotected their kids in the physical world and underprotected them in the online world, partially because parents are unwilling to fight with teens about their phones.

That said, parents are in an almost impossible position these days because parental permission is not required to open a social media account and age is not verified. We can buy them phones (like Troomi, Gabb or Pinwheel) that don’t have social media access, but it is very time-consuming and difficult to police every device kids have, especially when they use laptops to do homework. We can’t blame this problem solely on parents — we need governments to step up with better regulation. We also need to join together and help each other. So yes, let’s encourage kids and teens to get off their phones, but realize we can’t do that alone.

Overall, it seems unlikely that the rise of therapy caused the increase in teen depression that began around 2012. Therapy works better than doing nothing, even for teens, so if a proliferation of teens were getting therapy, severe depression should have gone down, not up. Parenting has become increasingly permissive for decades, not just during the last 10 or 15 years. Yes, more schools now focus on mental health and wellness, but that might be because more students are depressed and anxious; the causation might be reversed.

I agree with Shrier that parents should not be so quick to try to protect our kids, and that kids thrive with structure and clear boundaries. Blanket mental health interventions for all kids can backfire. But the message can’t be that all therapy is bad — too many teens are suffering too much, and therapy can help at least some of them. Until we have a better strategy than “shake it off,” we have to at least try.

Jean M. Twenge is a professor of psychology at San Diego State University and the author of “Generations” and “iGen.”

This story appears in the June 2024 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.