A decade ago, I attended a summer camp unlike any other. Called Tomorrow’s Women, the organization had flown more than 20 young women from Gaza, Israel and the West Bank to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The summer camp was based on the idea that, if left to politicians and governments, the decades-long conflict between Palestinians and Israelis would never end. Perhaps bringing together young women from both sides of the conflict, and breaking down perceived barriers, could plant the seeds for peace back home.

Memories of this trip came flooding back in October, when I turned on the news and saw footage of a 30-year-old Israeli mother being loaded into a truck by Hamas terrorists while clutching her infant and 3-year-old son.

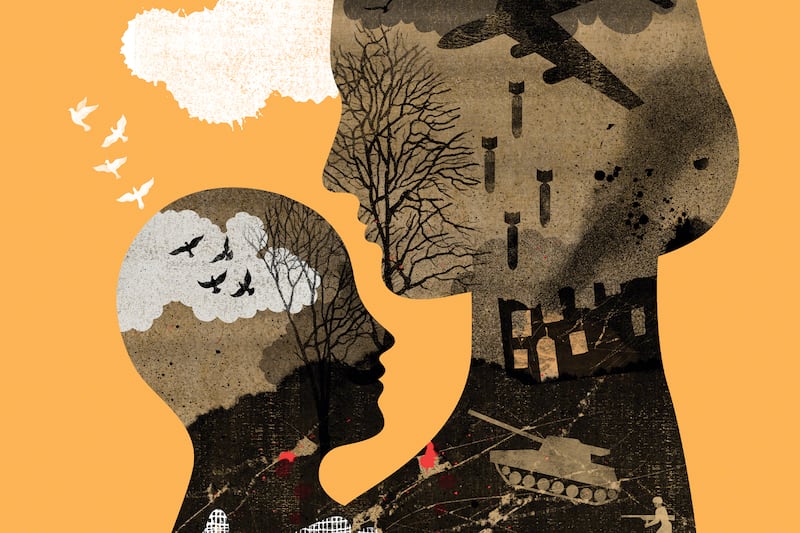

As a mother myself, I couldn’t imagine the horror of being kidnapped with my kids and being unable to protect them. I agonized over the stories of mothers and children being taken hostage and the 1,400 lives ended on Oct. 7, which has been called Israel’s 9/11. At the same time, I braced myself for what would come next.

Over the following days and weeks, as the death toll in Gaza mounted, I wondered: Where are those young women I met at the summer camp? Are they OK? What do they think about what’s happening?

My mind lingered on two counselors who had told me how coming to camp over the years had changed their perspectives. The Israeli woman had said, “I came like a book of facts, ready to shoot a fact at any Arab like an arrow. Once I started talking to Arab women, I realized I didn’t know anything about what was happening on the other side.” The Palestinian woman had described the unlikely friendship she forged with an Israeli camper. “All I knew about the other side was the military — I’d been through a lot of bombings and attacks. Now all of my Palestinian friends know I have a Jewish friend, and they’re shocked.”

What’s clear is that so many people directly and indirectly involved in the conflict feel unheard, misunderstood and mistreated. That’s something we can change, no matter where we live.

The us-versus-them dynamic

In early November, I reached out to both women on social media. The Palestinian woman from Ramallah replied immediately and thanked me for thinking of her. “Humanity is dead,” she wrote. “Little kids and women and families are being vanished, and no one is doing anything — only God is with them.”

She said her hope for peace had been extinguished by years of suffering at the hands of the Israeli military in the occupied West Bank. “Is it logical to live in peace with people who are hating you, killing and doing anything to make you suffer every day for years? There is a justified anger that we have been feeling for years and it’s getting bigger each day. … I’m sure what you hear or see is not even 2 percent of what we suffer here.”

An Israeli woman I met at the camp, meanwhile, echoed the sentiments of many Jewish Americans I spoke with who felt that Israel had been unjustly cast as the aggressor when it was Hamas that ignited the current war with its Oct. 7 terrorist attacks. “This is different than any other war Israel has been involved in,” she wrote. “After a week of shock, when the fear took over and the heart couldn’t carry this, we started seeing on social media people blaming Israel for what happened. … I’m willing to receive such clashes from Palestinians, but not from people who don’t live here.” She also voiced frustration over Palestinian leadership and said she wished “they would invest in the safety of their people before investing in ammunition to attack Israel.”

It made sense to me that the former campers, like my American friends with family ties to Israel and the Palestinian territories, were entrenched in grief that included rage toward the other side. What surprised me was that so many observers with no obvious connections to the conflict were opining against one side or the other while excusing either the terrorist acts that claimed the lives of 1,400 people or the bombing campaign that had killed thousands and thousands more (including more than 6,000 children).

As a mother who weeps for every dead child and bereaved parent, as an American of Jewish descent, and as an author who has reported on conflict and peace-building efforts in multiple countries, I am dismayed that so many of us worldwide — Jews, Muslims, Christians, Americans and global citizens — have been legitimizing dehumanization, terrorism and war.

Excusing such violence or glorifying one side perpetuates the us-versus-them dynamic that brought this hell to humanity’s Holy Land. While mired in that mentality, all the questions we ask are just shades of the same dangerous mindset. Who is to blame and who is virtuous? Are you on my side or the enemy’s? How will our side win?

During these divisive times, we would all do well to take on the practice of listening to understand instead of listening to persuade.

An immoral argument

Those questions lead to the immoral argument that the slaughter of innocent civilians is a necessary means to an end. What if, instead, we dedicated ourselves to the belief that every child deserves to be safe and cared for and that every person is worthy of respect?

If we believe that every human life has value and that all children are our children, we must mourn every life lost and every child hurt.

Maybe all of us, not just those directly involved in the Middle East conflict, have a case of what researchers call “competitive victimhood.” This concept means that groups mired in conflict compete over which group has suffered worse abuses, steeping new generations in the idea that their own group has suffered more and is therefore entitled to act in certain ways. Here in the U.S., people who relate more to Palestinian suffering under occupation justify terrorist attacks, while those who relate more to antisemitism and the Holocaust excuse the Israeli bombardment.

What’s clear is that so many people directly and indirectly involved in the conflict feel unheard, misunderstood and mistreated. That’s something we can change, no matter where we live. Research shows that being curious, asking questions and listening with the intention of learning instead of persuading decreases conflict and increases the chance of meaningful connection.

During these divisive times, we would all do well to take on the practice of listening to understand instead of listening to persuade. While empathic listening won’t turn fundamentalist militants into peaceniks, it can diffuse the widespread blame and resentment they feed on — especially if it ultimately leads to the resolution of grievances.

Those of us who believe that all people deserve life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness should also ask big questions that are aligned with that belief — and with the principles of love and tolerance espoused by the prophets of all three major world religions birthed in the Middle East.

We should dedicate ourselves to exploring questions like: “What would it take to ensure that every child is loved, valued and protected, no matter their race or nationality? What kind of nations, strategies, systems and habits would increase the likelihood of all people feeling heard and respected, and having the resources they need to thrive?”

If we focus on those questions, maybe we’ll eventually find answers that lead us out of endless cycles of entrenched conflict and competitive victimhood in which no one can possibly win. Until then, humanity will continue to lose.

Megan Feldman Bettencourt is the author of “Triumph of the Heart: Forgiveness in an Unforgiving World.”

This story appears in the January/February 2024 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.