There’s no question the bond between fatherhood and marriage is weaker today than it was 60 years ago. Whereas almost 80% of children were raised in an intact, married home with their father in the early 1960s, today only about 51% have that privilege. In the face of what seems like a fraying father-marriage bond, some left-leaning men’s advocates like Richard Reeves would like us to accommodate this family dynamic.

According to Reeves, the author of “Of Boys and Men,” we are supposed to make our peace with the attenuated bond between marriage and fatherhood, understanding this is “the world we live in,” one “we had better make the best of” — and build a new norm of engaged fatherhood apart from wedlock.

“The goal then is to bolster the role of fathers as direct providers of care to their children, whether or not they are married to or even living with the mother,” argues Reeves. He believes that all fathers have a “moral obligation to be the best fathers they can be” regardless of their marital status.

We agree with Reeves about this obligation: fatherhood matters even if a marriage never took place or breaks down, and “becoming a divorced man can never be an excuse for being a deadbeat dad.”

But the quest to accommodate the culture’s anti-nuptial drift and build a new fatherhood norm apart from marriage is quixotic. That’s because not only is there a veritable chasm between married fathers and never-married fathers when it comes to their involvement and engagement with children today, but we have new evidence that, culturally, men who embrace the institution of marriage are much more likely to become fathers in the first place — and devoted dads in the second place.

To wit, the very men who reject the low view of marriage held by liberals are the ones most likely today to become dads and actually provide care for their children.

But, first, let’s consider a new Institute for Family Studies report by Wendy Wang on the links between marriage, residence and fatherhood involvement. How much are never-married and nonresident dads serving as “direct providers of care to their children,” compared to married dads?

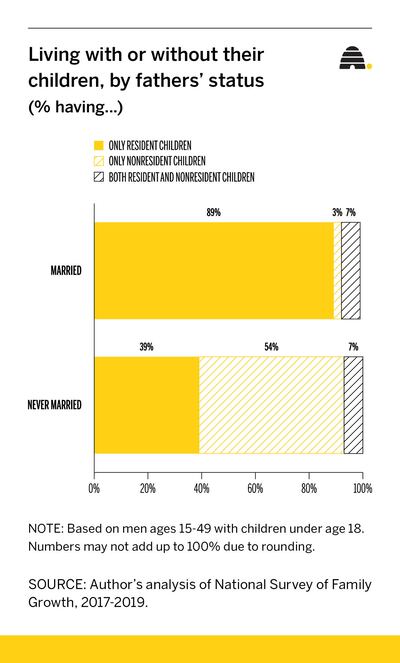

Obviously, it is much easier to provide direct care to your children if you live with them. And Wang finds that nearly “90% of married fathers live with their children, with only 3% having only nonresident children and 7% having both resident and nonresident children. On the other end, only about 40% of never-married fathers live with their children. A majority of never-married fathers live apart from either all (54%) or at least one of their children (7%).”

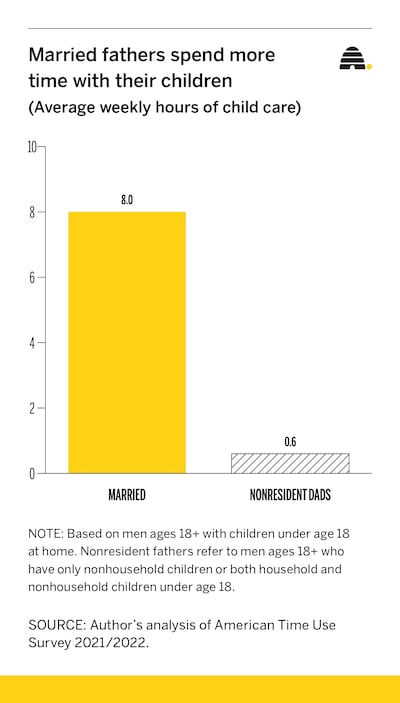

And when measured more precisely, the difference between the average weekly hours of direct care that married fathers with children under age 18 at home provide for their kids versus that provided by nonresident dads is staggering. Married fathers provide eight hours of care to their kids per week in 2021-2022, up from 6.8 hours two decades ago. By contrast, nonresident dads spent an average of 0.6 hours — or just 36 minutes — per week with their kids. So, clearly when it comes to being an engaged dad, married fathers have a major advantage.

Reeves also argues that a cultural shift has affected our support for marriage and our willingness to get and stay married for the sake of our children — and that we have to grapple with this cultural change. He’s right about that. The share of Americans who believe that it is “important” for unmarried couples who have had a child together to “legally marry” dropped from 76% to 60% between 2006 and 2020, as did the share of adults who say divorce is “unacceptable.” He thinks we need to accommodate this cultural shift.

But this view does not take into account the fact that men who reject the anti-nuptial currents flowing through our culture — men who still value marriage — are not only more likely, today, to get married, but also to become fathers and live with their kids.

To investigate the relationship between men’s marriage and family attitudes and their family choices, we rely on data from the American Family Survey, fielded by YouGov in 2022 and sponsored by the Wheatley Institute/Deseret News. Here are some of the findings.

Marriage and men. Men ages 18 to 55 who agree that “children are better off if they have two married parents” are more than twice as likely to be married than those who disagree, and this association is robust to controls for age, race, ethnicity and education. This gap also tells us that America’s marriage divide is not only about class, it is also about culture. The kinds of men who embrace marriage as an institution are more likely to be married today.

Men and fatherhood. Men who connect marriage to children are also markedly more likely to have kids in the first place. In fact, men ages 18-55 who embrace marriage are 19 percentage points more likely than those who don’t to have them, and this association holds even after controlling for age, race, ethnicity and education. This pattern is consistent with demographer Lyman Stone’s observation that marital status remains a potent predictor of fertility in America. As fatherhood becomes more selective, with fewer and fewer men becoming dads, we expect the relationship between holding a marriage-friendly worldview, being married and having children will only strengthen.

Father-present men. Fathers ages 18-55 who connect children to marriage are also 11 percentage points more likely than those who don’t to actually live with their children. Fathers who disagree that children are better off with two married parents are over twice as likely not to live with their children.

The negative relationship between taking a low view of marriage and living with your children holds up even when we control for age, race, ethnicity and education. This is noteworthy because residential fathers are not only much more likely to see their kids on a regular basis but also are much more likely to forge warm, engaged and authoritative relationships with their children.

Culturally speaking, we see evidence that men who embrace the connection between marriage and children are markedly more likely to be married, to be fathers and to live with their children. Because the data is cross-sectional, we obviously cannot say for sure that their normative orientation has caused these family behaviors. It may be, for instance, that the kinds of men who have succeeded in marriage and family life are more likely to adapt a marriage-friendly mindset. But, if nothing else, this new analysis tells us that men who take a more progressive view of marriage and family life would seem to be less likely to become the kind of men that Reeves advocates for — that is, men who embrace the generative power of fatherhood by becoming dads and playing a central role in loving and being present to their children, outside of marriage.

Debates about marriage and fatherhood often revolve around family structure. And while there is no question that the structure of marriage facilitates better fathering for most men, as the new Institute for Family Studies report shows, we have not until now investigated the relationship between marriage culture and fatherhood in men’s lives. In America today, marriage-minded men are much more likely to end up becoming fathers and living with their children. In other words, the kind of men who embrace the norm of marriage are more likely to be the kind of men who end up becoming fathers and forging day-in-day-out relationships with their children.

Brad Wilcox, a professor of sociology at the University of Virginia and director of the National Marriage Project, is the Future of Freedom Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies and a visiting scholar at the Sutherland Institute. He is the author of the forthcoming book “Get Married.” Wendy Wang is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies. Her research focuses on marriage, gender, work and how family is linked to individual success and well-being. She is a former senior researcher at Pew Research Center and received her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Maryland. Elizabeth Self is outreach coordinator at the Institute for Family Studies. She previously worked in research with sociologist Christian Smith and studied Great Books, theology and constitutional studies at the University of Notre Dame.