Is there anything more American than flying to London on July Fourth to see Bruce Springsteen in concert?

I watched 60,000-plus British fans go crazy for the Boss. It made me think that if we Americans had Springsteen in 1776 there would have been no need to fight a war for our independence. The British would have happily traded the 13 colonies for a free show.

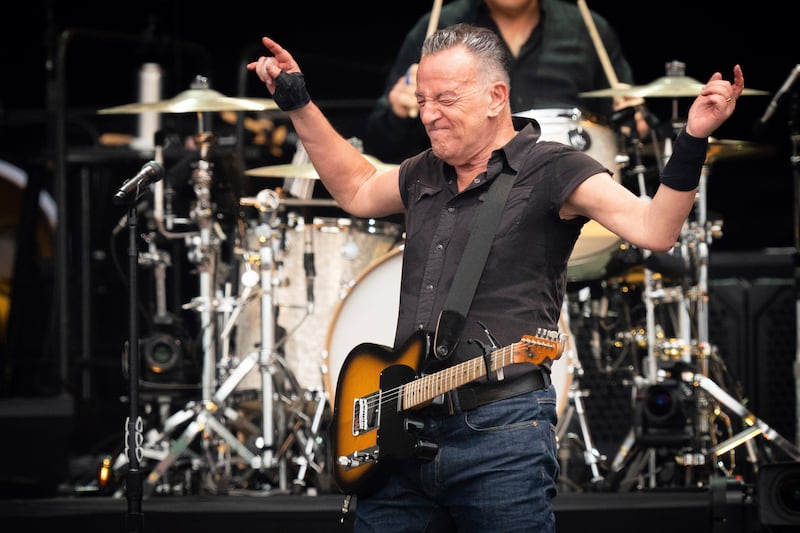

Watching him shred on stage for three hours is exhausting for an audience member. One can only imagine what it feels like for a 73-year-old man.

You read that right: Bruce Springsteen is 73. He is, to my mind, our greatest living artist. Hearing him play a song like “Born to Run” (1975) alongside a number like “Ghosts” (2022) made me realize that this guy has been at the top of his game longer than I’ve been alive.

Part of what makes Springsteen such a deep expression of American character is that he wasn’t born on the top of the mountain. He clawed his way up.

It’s a story he tells beautifully in his Broadway show, available to watch on Netflix.

Little Bruce held his first concert when he was 7 years old. The whole neighborhood came. His rented guitar shone in the sun. He whooped and he hollered. He danced and he shimmied. He pointed at the sky and he implored the audience to scream.

Up until that point, Springsteen’s life had, by his own account, been an endless loop of school, homework, church and green beans.

“But then,” as Springsteen tells it in his one-man show on Broadway, “in a blinding flash of sanctified light … a new kind of man … just a kid from the southern sticks … split the world in two.”

It was Elvis on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

The revolution had been televised right under the noses of the powers that be — and remarkably, those powers had not shut it down. The fateful event took place on a Sunday night in 1956 and young Bruce, living somewhere in nowhere New Jersey, suddenly knew that there was more — “more life, more love, more hope, more truth, more power, more soul.”

He continued: “I listened, I believed, and I heard a mighty call to action.”

At that first backyard concert, Bruce never actually played the guitar. Elvis had made it look so easy. When Bruce held his first guitar in his hand, he kind of hoped it might play itself. He thought his job was just to look cool.

Once he realized the crowd was laughing at him, not with him, Springsteen started to put in the real work. He practiced for hours alone in his room, building up his guitar chops. He spent Friday nights watching local bands play gigs at YMCAs and high school dances; he stood in front of the lead guitar player to see what he was doing, then went home and tried to play what he’d seen.

The secret to being Bruce Springsteen has two parts: imagine a magnificent character for yourself, then put in the work to become it.

That’s the same duality that defines the American experiment. Dream a glorious nation, then labor to achieve it.

You can see this “two-ness” running both through Springfield’s body of work, and through American history.

Listen to his early albums and you have a young Bruce Springsteen who will kill to break free. He is “Born to Run,” “Racing in the Streets,” to get out of this place, to exit St. Mary’s Gate and declare his own personal “Independence Day.”

And then there’s the side of him that craves stability and tradition. These days, Springsteen lives 10 miles from the house where he grew up. He says that the most meaningful part of life is not being a rock star but being a dad and a husband. He writes about the comfort he gets from church bells chiming, the same church bells that he disdained as a kid.

At the end of the Broadway show, he leads the audience in “The Lord’s Prayer.”

In fact, he calls his whole musical career “a long and noisy prayer,” not ultimately about discovering himself, but about understanding the people around him.

Think about the various characters Springsteen conjures in his songs. He sees the decent cop who lets his criminal brother escape, the ex-con trying to walk the straight line, the returned Vietnam vet seething in the “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” the high school hero in late middle age, the innocent West African immigrant who gets shot 41 times because of the color of his “American Skin,” Tom Joad as a Mexican migrant worker.

He sings these songs in such a way that we not only identify with the characters we like and resemble, we learn something about the ones we dislike and consider alien.

If Bruce Springsteen didn’t exist, America would have to create him because he is so essential to our national identity.

And you know what story Springsteen chooses to tell? That if you didn’t exist, America would have to create you. Because the distinguishing feature of American identity is that it regards each person on this sacred ground to be essential.

The magic trick that Bruce Springsteen performs is making this random assortment of individuals feel like a nation.

That’s why America is a potluck, not a melting pot. A singalong, not a solo. An improvisational jazz show, not a strictly ordered symphony.

If our people, in all their splendid variety, don’t contribute, well, the nation doesn’t feast.

It is only in understanding our collective story that the ultimate meaning of our individual stories are revealed. And it is only in the gathering of our individual stories that we have a collective story.

Eboo Patel, the founder and president of Interfaith America, is a contributing writer for the Deseret News, the author of “We Need to Build: Field Notes for a Diverse Democracy” and the host of the podcast “Interfaith America with Eboo Patel.”