When I was about 11 years old, I walked home from my summer camp. I think I was just tired of seeing all of my friends’ parents pick them up on time. The clock would hit 6 p.m., everybody else would be gone, and my brother and I would just be sitting there in the lobby of the B.R. Ryall YMCA, watching for our mom or dad to walk through the door.

My family was loving, but at that moment, was kind of coming unglued a little. And I felt like a piece that was falling.

It was stupid to walk home. I didn’t even really know the way. I think I took three or four wrong turns, but I eventually got there.

I remember my dad pulling up in the driveway in his blue Oldsmobile sedan, shouting “There he is!” and pointing to me — on the roof.

I had climbed a tree in the backyard and was putting a leg through my bedroom window, getting in the same way I used to sneak out.

I also remember a car pulling up behind my dad. It was carrying several of my summer camp counselors. Someone must have summoned them into service. I watched from the roof as my dad shook each of their hands and thanked them profusely for helping look for me.

That night, I played things down as much as possible. I kept on saying that nothing was wrong. I just went for a stroll, found myself halfway home and decided to walk the rest of the way. What was everyone freaking out about?

My parents, I think, were too exhausted to pry any further. They told me that I had inconvenienced a lot of people. Cars were sent in every direction. People were walking through the woods behind the Y, scared that they might find me in a ditch.

The next day I went back to summer camp even though I didn’t really want to. At the very least, I had frightened people and wrecked their evenings. Also, I wasn’t really an angel in summer camp to begin with. I thought that this would just add a stain to my already splotchy reputation.

So I got dropped off and I kind of scooted into my little summer camp group trying not to be noticed, but I somehow caught the eye of the assistant director, Debbie, the bad cop of the staff.

She’s doing count-off with her group of kids in her typical stern fashion, and she sees me and starts to walk over, and her facial expression changes. And she gets to me and leans over and puts her hands on my shoulders and says in this gentle, very-unlike-her voice: “Hey kid, I tired my feet out walking the woods looking for you last night. You had all of us very worried. I’m glad you’re safe. You are one of my favorites.”

And then she took her hands off my shoulders and walked back to her group.

Summer camps have a purpose. They make kids feel safe and loved. Camp counselors carry this work out. Debbie did her job, and did it well.

But here is a good way to get zero views on a TikTok video: Talk about the importance of doing your job well.

We live in a moment when the current is with the people who are shouting, “Tear down the institutions,” not the people trying to run them better.

We also live in a nation that is running out of volunteer firefighters — and most fire departments are staffed by volunteers. We keep lowering the standards for people to enter the teaching profession and the military, and still not enough people are signing up.

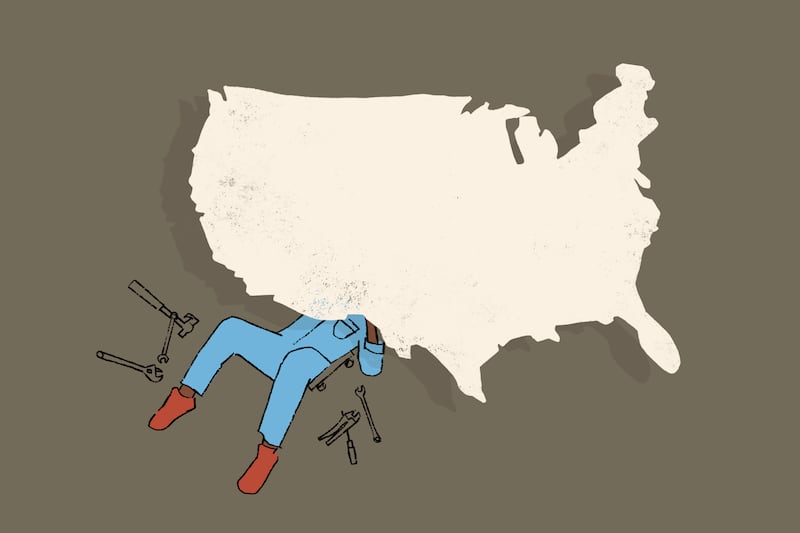

Our institutions are in trouble. Do we really need to delegitimize our institutions any further? A society cannot have more arsonists than architects.

Throwing your fist in the air doesn’t prepare you to have your hands on the wheel. Critique is not a qualification for leadership.

Social change is not about a more ferocious revolution; it’s about a more beautiful social order. A social order is a network of durable institutions, and trust me, institutions don’t rise from the ground or fall from the sky or magically appear after your post gets a million likes. People build institutions, brick by brick and day by day.

Like William Carlos Williams’ red wheelbarrow, so much depends upon people doing their job well in institutions.

In the “Bhagavad Gita,” the Lord Krishna reminds the warrior Arjuna that there is sacredness in doing your duty. The Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh says when you are washing the dishes, just wash the dishes. In the FX series “The Bear,” Sydney asks her dad, “Why can’t we give everything we have to everything we can?”

In basketball practice, there’s a drill called the “three-player weave.” You pass the ball ahead and loop behind the player you passed it to. When it goes right, the last player gets a full-speed layup. It’s like ballet on the basketball court.

The ball is not supposed to touch the ground. When it does, the coach blows the whistle and says: “Do it again.”

You can call that basketball. I call that nation building.

Eboo Patel, the founder and president of Interfaith America, is a contributing writer for the Deseret News, the author of “We Need to Build: Field Notes for a Diverse Democracy” and the host of the podcast “Interfaith America with Eboo Patel.”

This article is adapted from a speech given by Patel at The Nantucket Project.