In my field, economics, there’s a term for what happens when individuals with free access to a natural resource make decisions based on their own needs, regardless of the negative impact on others. It’s called “the tragedy of the commons.”

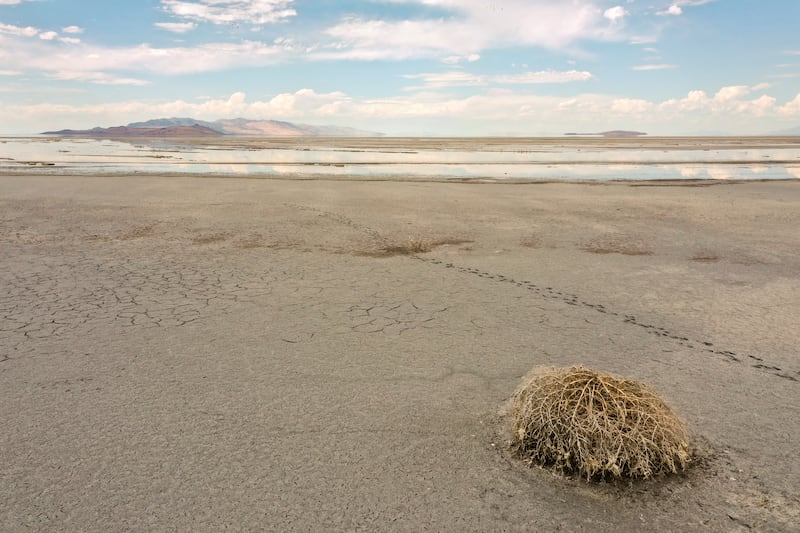

Visiting the Great Salt Lake with my family recently, I realized how much this concept applies to Utah’s most famous natural wonder, which is shrinking because of increased aridification.

The Great Salt Lake represents more than recreation and tourism for Utah. The lake’s unique geography provides both an ecosystem for unique wildlife, and its winter “lake effect” ensures water for the next season. With no natural outlets, the freshwater from its many tributaries cannot escape, giving the lake its extreme salinity.

Markets and prices efficiently allocate private goods that are both excludable (well established property rights) and rival (my consumption reduces your consumption). For example, I can prevent someone from taking my candy bar, and, if I choose to share, the candy is easily split between friends. However, the Great Salt Lake (like all water in the West) is rival, but non-excludable, setting up the tragedy.

Given that the Great Salt Lake is a common resource to be shared by all, each individual citizen will consume water to serve their own self interest. Farmers, homes and businesses use the resource until their individual marginal benefit is less than its marginal cost. Put simply: I water my lawn, take a long shower or irrigate my crops with an antiquated system because the benefit of doing so is greater than the price I pay.

The term “common” came from feudal England towns built around a grassy field where citizens would let their livestock graze. However, as more came to town, they noticed the animals were leaner because the grass was all gone.

We call this a tragedy because when decision-makers realize their predicament, it is usually too late to act, the resource is depleted and the crops, livelihoods, ski resorts and way of life are gone forever. It requires great sacrifice to free ourselves from the trap. We must work together as a community to overcome our self-interested tendencies to ensure our survival. As the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote, we must give up some desires so we can “come out of nature” and enjoy higher rights as citizens in a well-functioning society. Living in democratic republic takes work, effort and discipline.

To overcome the tragedy of the commons, Nobel Prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom proposed a hybrid approach that combines market forces with proper policy. Let’s consider it with regard to the Great Salt Lake.

First, water requires efficiently allocated property rights so that citizens understand how much of the resource is available to them and are able to transfer that right for more efficient use and recoup costs. Recent changes to Utah laws allow farmers who own water shares to “sell” these back to the Great Salt Lake. This policy rewards efficient water usage and gives a financial incentive for agriculture to switch irrigation systems. This change creates a platform for a market-based approach.

Second, policymakers need to consider the price of water and whether it incorporates the harm that overconsumption has on the Great Salt Lake’s unique ecosystem. Given this risk, the price of water, particularly secondary water, is too low. In the presence of a negative externality, individuals will consume more than is optimal because the benefit of doing so outweighs the artificially low cost; especially in agriculture, which constitutes the vast majority of water usage.

No one wants higher utility costs, but if we do not appropriately “price in” the harm, then we will be stuck in the tragedy of the commons. However, policymakers are reluctant to do so given potential backlash from voters. As the character Cassius in “Julius Caesar” lamented, “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.”

The tragedy of the Great Salt Lake commons requires both a platform for better market solutions and public policy to consider the harm of overconsumption. Both of these issues are possible, but only with appropriate tradeoffs, especially in the face of increased population growth.

Thankfully, the tragedy of the commons notwithstanding, community spirit is part of our American identity. As Alexis de Tocqueville wrote, “in the United States … they seek each other out and unite together once they have made contact. From that moment, they are no longer isolated but have become a power seen from afar whose activities serve as an example and whose words are heeded.”

That was true in the 19th century. The future of the Great Salt Lake may rest on whether it’s true today.

Michael S. Kofoed, @mikekofoed on Twitter, is an associate professor of economics at the U.S. Military Academy and a research fellow at the Institute of Labor Economics. A Utah native, he holds degrees in economics from Weber State University and the University of Georgia. His opinions are his own and do not represent the U.S. Military Academy, the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.