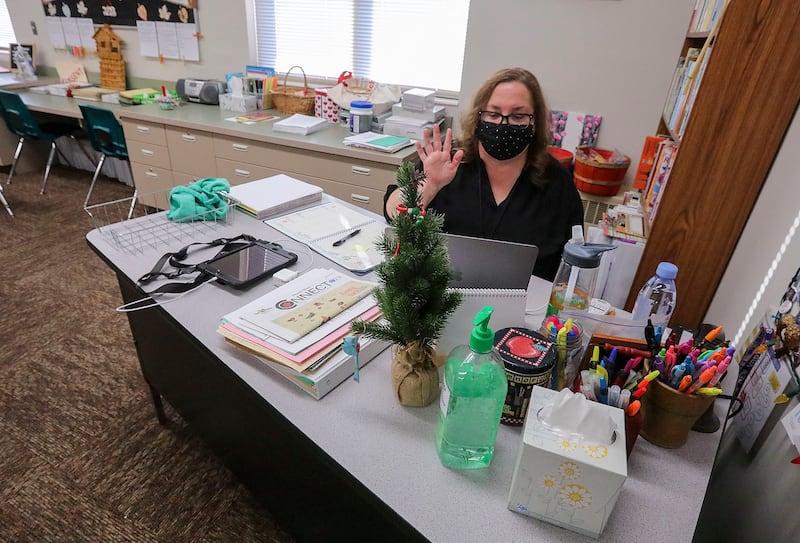

No change during the COVID-19 pandemic was more salient and divisive than school closures and the pivot to online learning. Almost at the push of a button, students ranging from pre-K to graduate school were learning how to share screens and “Zoom” while teachers and parents balanced multiple priorities when home and school occupied the same physical space. Now that we are returning to a somewhat “normal” routine and a new school year, we should ask ourselves, “Are the kids really all right?”

It’s complicated, but there is real reason for concern. Let me explain.

Estimating how online learning and school closures affected students reveals a common issue in social science: selection bias. Imagine a clinical drug trial for a new blood pressure medication. Patients walk into a research facility and are divided at random into two groups. One group receives the new drug while the other is given a placebo. A few months later, researchers evaluate both groups to determine the drug’s effectiveness. This procedure is called a randomized controlled trial.

Now imagine if researchers allowed either the physician or even the patients themselves to select who received the drug or the placebo. Some doctors might pity patients who suffered the worst symptoms and give them the pill, or patients who were hypervigilant about their health (like marathon runners) might choose the drug for themselves. We cannot be sure whether the doctor’s concern, the runner’s healthy habits or the new medicine caused the better blood pressure. In this case, correlation does not imply causation.

Measuring how students fared during the COVID-19 pandemic is equally tricky. School districts, mayors, governors and other policymakers chose either closure, online, hybrid learning or a quick return to the classroom. Infection rates, timing of spring break and political calculations all played a role in these nonrandom policy decisions.

Many parents also moved their students into learning pods, private schools or homeschooling out of a desire to have an in-person experience for their children. It is difficult to parse out the effect of infection, parental unemployment or trauma from the loss of loved ones from actual learning loss from the online switch. We cannot truly know the effects without a setup like a clinical trial.

Luckily, my colleagues and I at the United States Military Academy at West Point received a unique opportunity to study this question in an experimental setting. West Point is unique given our mission to train cadets to be Army officers. West Point randomly issues everything from roommates to class schedules to professors. There are no favorites, and if the Army wanted you to have preferences, it would give those to you, too.

During the pandemic, the academy allowed us to randomly assign cadets to either take an introductory economics course online or in-person, allowing for social distancing. Our setup was about as close as you can get to a randomized control trial during the pandemic in a higher education setting.

The curriculum, assignments and exams were uniform across instructors, and each instructor taught half of their courses online and half face-to-face. Our results were striking. Students in the online sections did demonstrably worse on every assignment and exam; even with mandatory attendance and cameras on. We found a grade drop of about a quarter of a letter grade. For perspective, other studies have found to make up that gap a student would need a tutor. (For ethical reasons, we did adjust the grades of students in online sections upwards by the amount of the learning loss.)

Given these results, we wanted to learn what made in-person instruction so valuable. We asked students to rate their classroom concentration, social connectedness to their teacher and peers and persistence in turning in assignments. These measures dropped across the board for those in online sections — even compared to the same instructor but in the different modality. It appears that having a face-to-face relationship is key to deep learning.

Arguably, our setting was unique, a military academy that recruits high-ability students into a disciplined environment. However, if we were to find learning gaps at West Point, they probably exist elsewhere. Other studies have shown similar results by comparing similar K-12 school districts that were online longer than those quick to re-open and others find the largest learning loss in decades. We have an education crisis on our hands.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced us to make hard tradeoffs. Balancing the public health threat, particularly for the elderly and immunocompromised, required adjustment to daily routines. Masks and immunizations proved helpful in mitigating the disease. We cannot allow students, especially those academically at-risk, to fall behind. Public investment in tutoring, additional instruction and retaining teaching talent must be a priority. We cannot change the past, but our choices for the future will reveal our values.

Michael S. Kofoed, @mikekofoed on Twitter, is an associate professor of economics at the U.S. Military Academy and a research fellow at the Institute of Labor Economics. A Utah native, he holds degrees in economics from Weber State University and the University of Georgia. These opinions are those of the author and do not represent the U.S. Military Academy, the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.