On the evening of Nov. 2, 1948, President Harry S. Truman settled into the Elms Hotel in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, to receive the results from his bid for reelection. The polls were grim.

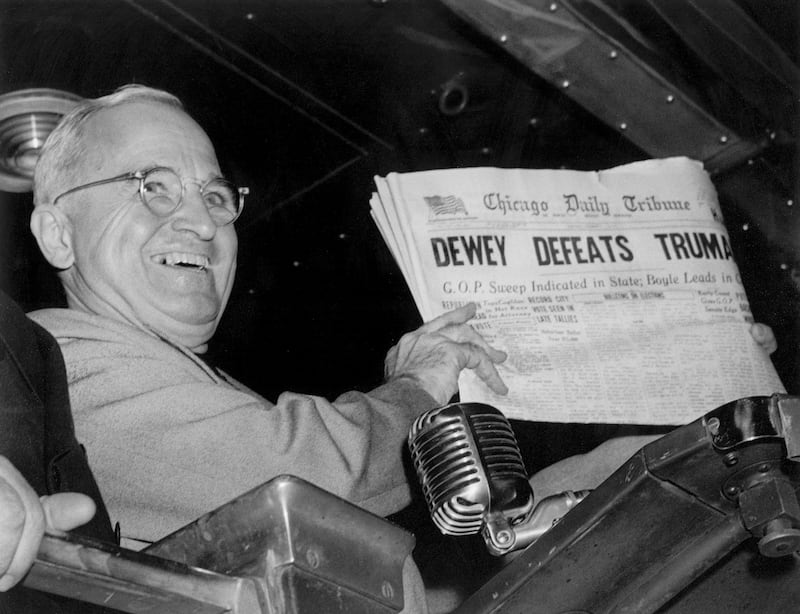

They were so bad, in fact, that radio broadcasters told their audiences that while the president remained ahead in vote counts, there was no possible way that he would defeat the Republican candidate, New York Gov. Thomas E. Dewey. The Chicago Daily Tribune was so confident in the outcome that it began delivering newspapers with the headline “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN” splattered across the front page.

History sometimes takes ironic paths. Truman resoundingly defeated Dewey for a second term and the newspaper mishap resulted in an iconic photograph in presidential politics: Truman flashing his bright smile, holding the newspaper and shouting, “That ain’t the way I heard it”.

In 1948, like now, America was deeply divided on numerous fronts. What should the post-war world look like? What to do with the New Deal programs passed by the Roosevelt administration? How would we handle the Soviet Union? Despite the bitterness of the presidential cycle (that also featured segregationist candidate Strom Thurmond), Truman’s approval ratings soon spiked nearly 35 percentage points in the Gallup Poll. Many Americans, it turns out, were willing to trust a president for whom they did not vote.

Could that sort of social trust happen again today?

Social trust, which Pew Research Center defines simply as “faith in people,” is like a beautiful tulip. Gardeners plant the bulbs months in advance with hopes that the fragile flower will grow, thrive and bloom. Usually, the hope and the work all come together and result in a single beautiful blossom. However, in a single moment, a lawn mower, a stray baseball or (in my family’s case) a hungry deer can destroy the entire project. Similarly, trust must be painstakingly cultivated but is easily destroyed.

Trust is the glue that holds our democratic system together. If we cannot trust our own neighbors, institutions, elected officials or communities to act for the greater good, then heavy-handed laws and regulations (or, conversely, chaos) will take their place. All these consequences stifle innovation, entrepreneurship and quality of life. They also are contagious. For example, a researcher found that when news reports of local government corruption increased, cheating by area school children jumped as well.

It’s not impossible to regain trust once it is lost, but it does require a high sacrifice. I was recently impressed by an interesting field experiment conducted in partnership with the ride-sharing company Uber.

When I open the Uber app, it promises me that I will arrive at my destination by a given time. As someone who tends to cut it close in airports, this transaction requires a lot of trust on my part.

However, it is not uncommon for a driver to get lost, not show up or go the wrong way. A problem like this may cause me to never use the app again and turn to Uber’s competitors. During the experiment, researchers randomly assigned 1.5 million upset customers to one of three “treatments.” The first was a simple apology, the second was the same apology with a coupon for a free trip, and the third was no outreach at all from the company.

It may not be shocking to find out that customers with a coupon were more likely to use Uber again, but surprisingly the simple apology did worse than no interaction at all from the company. As the old economist joke goes, talk is cheap because supply outstrips demand. The company offended more customers with empty promises and slogans than if it had said nothing at all.

Cable news, social media, conspiracy theories and a lack of civic education are all tearing apart our social fabric. It will cost something of our own souls to rebuild our social trust. We need to be willing to compromise, see the good in others and even give up some habits and policy preferences to ensure we aren’t just offering cheap talk.

As Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints recently said, “conflict is inevitable. contention is a choice.” We may not agree with our neighbors on issues ranging from the cultural to the marginal tax rate, but when we begin to see them as less valuable because of a differing view, we destroy social trust.

As Uber learned, regaining trust is costly. Like gardening, it requires sweat, perspiration, frustration and a little luck. However, as Abraham Lincoln plead with a country at war with itself, “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. … The mystic chords of memory … will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

Michael S. Kofoed, @mikekofoed on Twitter, is an associate professor of economics at the U.S. Military Academy and a research fellow at the Institute of Labor Economics. A Utah native, he holds degrees in economics from Weber State University and the University of Georgia. These opinions are those of the author and do not represent the U.S. Military Academy, the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.