When John Lasseter strode onstage at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion to accept the 1996 Academy Award for special achievement, he carried with him a Buzz Lightyear action figure and a Woody doll. At the glass podium, he set the iconic spaceman and cowboy toys face down beside his Oscar, then described “Toy Story,” the world’s first computer-animated feature-length film, as a labor of love for his then-fledgling studio.

The director and Pixar executive spoke with a steady timbre indicative of someone aware he’d forever altered the course of entertainment. “‘Toy Story’ carries a human spirit that shines even brighter than its computerized glow,” he said before walking off stage and leaving, curiously, the award and toys behind on the podium. Soon, the characters, just as they do in the film, stirred to life on an enormous screen. Woody stood to thank the Academy with his trademark concoction of charm and arrogance; Buzz beamed his laser at the Oscar statue in a predictable attempt at heroism. The audience laughed and cheered as if the two were of flesh and blood. Such ardor might appear overdone in another context. Here, it risked understatement.

“Toy Story” reimagined what animation could be. It pioneered computer-generated features and proved the use of technology didn’t have to sacrifice storytelling or soul. “You can see the filmmakers are not talking down to the audience,” says Jake Friedman, an animation historian at New York University and the Fashion Institute of Technology, of “Toy Story.” “There really are no child characters in the movie. They are all adult characters who have these quirks and their quirks can be summed up in a sentence or two. … These are all about human relationships people can relate to.”

Walt Disney Studios helped produce the film in partnership with the newly minted Pixar, and it became the highest-grossing picture of 1995 — earning almost $400 million in worldwide ticket sales, worth about $800 million in present-day dollars. Nothing else quite like the film existed at the time, and its success signaled people wanted more. Disney forged an agreement to produce five additional movies with Pixar, an agreement that would later lead to an unprecedented repertoire of hits and Disney’s eventual purchase of the company. From its very first attempt, Pixar had evinced a novel approach to storytelling. Each subsequent creation would build upon that approach and rival it. At least ideally.

In nearly three decades since, Pixar has released a total of 27 features. Among them are titans like “Finding Nemo,” which revolutionized how the ocean is animated in cinema; “Up,” which struck such a chord with families that one Utah couple built their own Disney-authorized replica of the movie’s rainbow-hued house; and “WALL-E,” which secured recognition as one of the nation’s most important modern films by the Library of Congress. It is now expected of Pixar that every one of its films will similarly resonate and produce hundreds of millions — sometimes billions — of dollars at the box office. The studio is lauded as the gold standard for animation, a level of praise last extended to the Disney of yore. But that golden standard now shows its first signs of tarnish.

Pixar’s latest release, “Elemental,” which premiered in June, is a romantic comedy about two personified beings of fire and water, a tale of diversity and acceptance that’s been interpreted as the studio’s take on an immigration story. The film endured the worst premiere day box-office numbers Pixar has ever seen. Of its $200 million budget, it earned back $44.5 million in global box-office sales on opening weekend. And Pixar’s previous film didn’t fare much better.

Debuted in June 2022, “Lightyear,” a science fiction story about the fictional astronaut who inspired the Buzz Lightyear toy, barely broke even, grossing just under $227 million in ticket sales worldwide out of yet another $200 million budget. The downward slope could not have arrived at a more inopportune moment. Pixar, which refused a request to comment for this story, is still reeling from pandemic-induced theater closures that robbed its prior three films of proper screenings. These include Academy Award-winning productions that topped the charts on Disney+, their home platform, yet failed to generate impressive ticket sales.

“The problem with the American animated feature, as opposed to a live action feature, is that we’re never allowed a small film. It has to be a blockbuster or all these execs are disappointed. … That’s why you have these $250 million disappointments,” says Tom Sito, a veteran animator whose 32 film credits include “The Lion King,” “Aladdin,” “Beauty and the Beast” and “The Little Mermaid.”

Though pandemic and streaming woes are easily explained, Pixar’s most recent struggles occurred despite reopened theaters. The cratering earnings point to a possibility that the studio and its intended audience are growing apart. So far apart, it’s unclear whether the two can expect a reunion. “There was an old animator who worked on ‘Snow White’ who once told me the state of a studio is two flops from disaster,” Sito says. “One flop and they go ‘well, OK, we’ll learn from this.’ Second flop they go, ‘OK, time to reevaluate.’ And that means get your resume in order.”

Disney laid off 7,000 people the first half of this year, as part of a more than $5 billion companywide budget slash. For the first time in 10 years, the eliminated included Pixar employees. Among the 75 people let go were Angus MacLane and Galyn Susman, legacy studio employees who each played vital roles in the creation of “Lightyear” — MacLane as the director, Susman as the producer. Whether intentional or not, the decision to let go those who oversaw one of the studio’s latest disappointments sent a clear message: A new era for animation has emerged yet again. Though Pixar is no longer at the forefront.

Disney laid off 7,000 people starting in May 2023, including legacy Pixar employees who played vital roles in the creation of “Lightyear.”

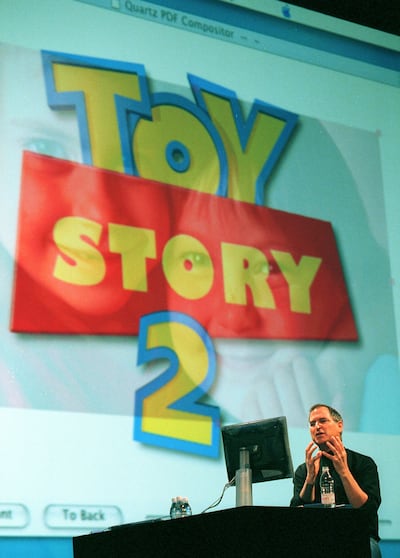

Pixar’s origin begins with “Star Wars” creator George Lucas. The filmmaker launched a computer division of his production company Lucasfilm in 1979 with the intent of shepherding computer graphic tools into cinema. Lucas tasked computer scientist Ed Catmull to head the team, which later grew to include animators like Lasseter. In 1984, they animated the division’s first short film. The project, “The Adventures of André & Wally B,” featured a mysterious baby blue biped of unknown species who runs from a vengeful bumblebee with a gargantuan stinger. The short film only amounts to a little more than a minute of silent content. It looks rudimentary compared to today’s standards, yet has all the hallmark characteristics of advanced animation: three-dimensional figures, hand-drawn textures, motion blur. But only when Steve Jobs purchased Lucas’ computer division in 1986 did the pursuit of compelling stories, more than technological advancement, materialize.

Jobs established Pixar as its own entity, but from the outset it collaborated with Disney to create CAPS, the Computer Animation Production System that made the industrywide switch from entirely hand-drawn to computer-generated films possible. But Pixar had other elements missing from Disney’s own animation studio.

Unlike the Disney princess films and other past feature-length hits, Pixar’s leadership decided no love stories or musicals would carry their productions. Instead, the studio pursued heavy-handed themes of life, death and family. Catmull described Pixar’s mission in a 2008 issue of the Harvard Business Review as one “to build a studio that had the depth, robustness, and will to keep searching for the hard truths that preserve the confluence of forces necessary to create magic.” It helped that it did so largely outside of industry pressures, a privilege impossible without the financial resources offered through Disney’s partnership. But once a final change of hands took place, in 2006, when Jobs sold Pixar to Disney for $7.4 billion, it reshaped the studio’s entire foundation.

What had made Pixar successful, as told by its founding fathers, was the ability to operate independently of Disney’s oversight. Catmull recalls in his book “Creativity, Inc.” that Jobs sold the studio to Disney under CEO Bob Iger because he came to view Iger as “a man of action … he was willing to buck the knee-jerk, industry-wide trend to oppose distribution of entertainment content on the internet.” That, and an agreed-upon caveat: Lasseter and Catmull would head both Pixar and Disney’s animation studios, to ensure outright autonomy.

Though much has changed in the 20 years since the acquisition. “I think Pixar’s biggest problem, at least if they’re wanting a better box office, is they got totally handicapped by Disney,” says one Pixar artist who was let go during the recent layoffs. He spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid backlash, and added most employees are left in the dark about the inner workings of the Disney-Pixar relationship. “Pixar basically carried Disney throughout the pandemic. Animated content made by Pixar on Disney+ is viewed so much more than any other Disney product. So Disney pushed Pixar into doing a lot of Disney+ stuff,” he says. “We have no idea whether it’s Pixar management, or it’s Disney forcing it. We’re almost always stuck in limbo.”

When Iger announced the launch of Disney+ in 2019, a $3 billion venture, he called it “a bet on the future of this business.” The streaming service offered a home for Pixar productions that would otherwise have been held for years due to the pandemic. But it also taught audiences — particularly families — to count on streaming for a cost-effective viewing experience. Statista reports the percentage of Americans who preferred streaming movies to watching in theaters stood at 30 percent in pre-pandemic 2018, but skyrocketed to 56 percent by the summer of 2020. And to Pixar’s detriment, that preference shows staying power. Pixar’s current chief creative officer Pete Docter told Variety in June the studio has inadvertently “trained audiences that these films will be available … on Disney+. And it’s more expensive for a family of four to go to a theater when they know they can wait and it’ll come out on the platform.”

Even with pressure on Pixar to continue feeding the streaming service, Disney+ has lost more than 11 million subscribers this year alone. It’s only expected to become remotely profitable by the end of next year. And while Pixar remains a critical component, it’s safe to assume its current business model could soon become unfeasible. The studio releases about a film a year, each averaging a budget of around $200 million. But as recent box-office performances prove, streaming has overtaken theater screenings to the point where these films are barely profiting from ticket sales. More studio failures could mean less incentive to approve another big budget picture.

All this arrives as the studio is left to grapple with internal changes. The team that first charted out the course of the company no longer exists. Jobs died in 2011. Lasseter left Pixar in 2018 after facing allegations of inappropriate touching and Catmull retired soon after. As the studio’s new generation vies to find its voice, in an era when animation feels more competitive and diverse than ever, that voice, it seems, fails to register.

“It’s just become more and more unsettling for a lot of people at the studio,” the anonymous ex-employee says. Feelings of wariness and confusion, he attests, have become pervasive for current and former staff. Likely because there’s no clear solution in sight. “It’s a struggle to diagnose truly what the biggest problem is with Pixar, because it’s not that the films look worse. It seems to be purely how the stories are speaking to people.”

Beyond problems posed purely by the streaming age, Pixar’s recent films have fallen under harsh scrutiny for changes in themes and content. The last two releases, “Elemental” and “Lightyear,” were each picked apart by conservatives as alleged arbiters of “wokeness.” “Elemental” included Pixar’s first-ever nonbinary character and “Lightyear” featured a scene with a same-sex kiss. “Disney works to push a ‘not-at-all-secret gay agenda’ and seeks to add ‘queerness’ to its programming. … Parents should keep that in mind before deciding whether to take their kids to see ‘Lightyear,’” conservative pundit Ben Shapiro tweeted. “Children are not adults. What may be appropriate for adults is not appropriate for children. That this must be said demonstrates that our society is in a state of moral collapse.” Parents chimed in on Facebook, noting their “kids didn’t even recognize Buzz” and “nothing stays original anymore.” “No child should watch this movie. Mine definitely won’t,” another commented. “Watched it with my kids and grandkids. We all hated it and were sorely disappointed.”

The cratering earnings point to a possibility that the studio and its intended audience are growing apart.

Some lump the nonbinary character and same-sex kiss together with the films’ lapse in financial success. This “get woke, go broke” mindset views companies that embrace progressive politics as alienating, charging them with virtue signaling — familiar ground in the culture wars that have consumed everything from beer advertising to curriculum bans in classrooms. So it’s no surprise when some on the right celebrate poor performances by progressive Pixar films, not in an America that’s this polarized. Pew Research Center reports the extent of this divide is exceptional when compared to other democracies.

Audiences are shifting in other ways, too. “I think today’s audiences, modern young audiences to be specific, are not as nostalgic about Pixar as millennials and Gen Xers who have been growing up on it for close to 30 years, and instead, they’re gravitating toward different types of animation, different studios, different brands,” says Shawn Robbins, chief analyst at Box Office Pro.

The first movie to surpass $1 billion in worldwide box-office sales this year, for example, was Universal Pictures and Illumination’s “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” (which, perhaps coincidentally, was venerated on the right for being “anti-woke” by casting a non-Italian to voice the Italian brother duo). “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse,” produced by Sony and Columbia Pictures, also became an out-of-the-gate blockbuster.

The “Worth It or Woke?” website — which rates films on exactly the parameters you’d think it does — gave the movie about an Afro-Latino superhero an overall score of 81 percent, pointing to right-wing approval. For context, the same website rated “Elemental” an abysmal 39 percent. “For a long time, Pixar finely walked that balance of pushing the envelope creatively from a narrative standpoint and writing-wise but still being friendly enough to most kids,” Robbins says. “It was inevitable it would kind of run into an ebb and flow in their evolution as a studio as more competition started to come around.”

Barring politics and competition, there remains a question of quality. The commentariat is littered with ruminations ranging from lukewarm to frigid for the infamous “Lightyear” and “Elemental.” Even Pixar’s own Pete Docter has notes for “Lightyear.” He told The Wrap in February that the meta storyline about the fictional astronaut movie that inspired the Buzz Lightyear toy — rather than the toy itself — “asked too much of the audience.” Jessica Winter expressed a similar sentiment in her dissection of “Elemental” in The New Yorker, where she reduced some aspects of the film’s execution to “remedial echolalia.” It’s a love story, while also an immigration story, while also, in Winter’s view, a less thorough example of world-building. She suggests that Pixar themes have shifted from heavy-hitting to just confusing. And that shift eats away at the studio’s strengths, once defined by universal appeal and accessibility.

And yet, though “Elemental” failed to resonate on the day of its debut, it’s since sprouted legs. The modern take on tearful and tactful storytelling recuperated in box-office sales by slowly crossing the threshold of $400 million in July. Those sales offer hope for the future of a studio that doubles as an animation bastion. At least one more original film is set to roll out next year, but if all else fails, earlier this year Pixar announced a fifth installment of the tried and true “Toy Story,” albeit without a release date.

When Woody and Buzz Lightyear accepted their first collective Academy Award three decades ago, spectators applauded as if the two were alive and aware of their praise. It’s not that the computer-generated renditions of plastic playthings appeared humanoid. Rather, they reflected qualities viewers could see in themselves, then saw them magnified on colossal screens. Their stories persist even while the grandeur of their stage shrinks down to laptop screens and television sets. But should Pixar’s success continue to idle, more is at risk than the studio behind the cowboy-spaceman duo. The loss of its characters and stories means the loss of a way to see the world and, in some cases, to see ourselves.

This story appears in the October issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.