“Do you want to see my favorite alligator?” A blond-haired man points out the reptile in question and begins to climb atop it, sitting on the base of its tail. He interlocks his fingers around its throat and leans back, pulling the gator skyward, making it look like a strange version of a rearing steed.

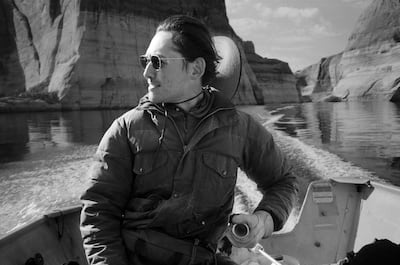

At this moment, surrounded by more than a hundred alligators at the Colorado Gators Reptile Park — a long way from home for them — Elliot Ross crouched in the dirt to shoot a portrait of man and beast.

“Why do you like getting on top of your alligator?” he remembers asking.

“I don’t know,” the man answered. “It’s just a way of saying hello.”

“Do you think he likes it?”

“I don’t know, probably not.”

“So why do you do it?”

“I don’t know. It feels good. I feel powerful.”

The man on the alligator glares into the lens, his leather work boots planted in the dark soil, his posture straight, his denim jeans worn.

The portrait is part of Ross’ photo survey “Good Grace,’’ a project and upcoming book in collaboration with the art collective M12 Studio. It aims to showcase the current state of Colorado’s San Luis Valley, where counties rank among the state’s poorest and driest.

Ross photographed the valley and its people for months. Now, looking back, this place gives that man’s response some context: In a region so rural and isolated, a sense of power and control can feel requisite.

The intersection of the Western landscape and people’s inner worlds defines much of Ross’ work.

A couple shielding themselves from the worsening Los Angeles heat under parasols; his family in northeastern Colorado praying out on the plains that an incoming supercell won’t damage their crops; a young woman in a quinceañera gown posing in front of the wall that divides the United States and Mexico.

These moments serve as a remedial view of the Western identity and experience that Ross has seen become romanticized, demonized and, above all, misunderstood.

“I get defensive when people refer to parts of the West as flyover states, which denotes there’s nothing of value,” he says. “And I see my job as to illustrate the value that exists in these misunderstood places with all of its layered beauty, its diverse identities, its silent histories, its cultural worth.”

“I get defensive when people refer to parts of the West as flyover states, which denotes there’s nothing of value.”

It started with barn cats and storms. Station wagons and tractors. Electrical outlets and Air Force drills.

In his early years, Ross photographed anything he could find to make sense of his surroundings. His grandmother had given him his first point-and-shoot camera when he was four years old, the same year his family moved from Taipei, Taiwan, to rural Colorado.

Quickly afterward, photography became a way to navigate the culture shock of switching from a dense urban environment in a city of skyscrapers and neon lights to a home on austere plains where the nearest neighbor or grocery store was miles away.

His mother’s side of the family is Taiwanese Chinese, but his father comes from a background of American farmers and ranchers. Ross’ childhood chores included bottle-feeding his 4-H calf every morning, clearing tumbleweeds and fixing fences.

He had no allowance in the traditional sense, but every month he got a new roll of film. His family made a pit stop at Walmart on the hour-and-a-half drive to church on Sundays to drop off his film when it was ready to get developed. Those photos often depicted his life on the family farm — all the chores, but also summers spent building forts, searching for arrowheads, dawdling through canyons.

Over time, the photographs have come to communicate the values with which Ross was raised.

“All the expected descriptors certainly come to mind: self-sufficient, resourceful, endlessly hardworking with high esteem for family and sometimes God,” he says. “I was raised with these attributes, and they certainly have shaped who I am today. I believe in the small things that create a sense of community, like long-winded conversations with your neighbor.”

Those traits, in their absence, stood out more after Ross left.

He valued living in New York City and working as a photographic assistant for luminaries Annie Leibovitz and Mark Seliger. But he also found himself longing for family, canyon country, high plains, the West’s variety and nuance and contradictions.

So he came home and kept his camera in his hand. He captured wrinkled hands grasping a Bible so worn its spine is held together with tape; combines gliding through golden fields; farmers taking in a sermon’s message at Cowboy Church; a child spinning around in a makeshift rain dance to fend off an incoming storm.

Ross was named a Critical Mass Top 50 artist the year he released these photographs in a collection titled “The Reckoning Days,” and held his first solo exhibition at the Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, Colorado, the following year. The response reasserted his decision to move back West, encouraging his newfound dedication to documenting the very world — once unfamiliar — that became his own.

“It was, in a lot of ways, an affirmation that I was on the right path,” he says. “I feel like I can make work here. Because I’m a part of this.”

Everywhere Ross goes, he carries a poem. It’s a one-page printout of Max Ehrmann’s “Desiderata.”

The paper is deeply creased from all the folding and unfolding, the reading and rereading. And of all the stanzas, the second one stands out the most to him: “Speak your truth quietly and clearly; and listen to others, even to the dull and the ignorant; they too have their story.”

He had the poem with him when he ventured to Naco, Arizona, in 2017 to meet and photograph those living along the nation’s southern border with Mexico. There, he heard a man yell from a distance while unholstering his gun. “How would you like to get yourself shot today?”

The voice belonged to John Ladd, a fourth-generation Arizona rancher who has frequently appeared on Fox News to speak in favor of more stringent border control policies. Ross de-escalated the conversation by explaining what he was working on. He told Ladd he just wanted to listen. So for half an hour, he did.

Like the West, Ladd is not one-dimensional. The cattle rancher expressed some skepticism about the border wall at the time out of fear it would grant the federal government too much power. Yet he felt deeply protective of his ranch, which had existed in his family for more than a century, because it was an extension of himself and his history.

“I think we both left from that interaction having learned a little bit more and feeling more compassion towards others,” Ross says. “Despite how angry, how out of control some situations and reactions start, I think it goes to show that there’s so much power in just listening.”

After their conversation came to a close, Ross asked to take a photograph.

Ladd’s portrait turned out. In it, he stands in front of his pickup truck, coated in a fine layer of red dust with a license plate that reads “BEEF.”

He’s in a denim button-up and jeans, a white cowboy hat in one hand as he squints into the sun. His eyes are nearly closed and a white mustache covers his lips, but somehow it’s still clear that he’s smiling.

“In my view, perceptions of politics and religion play heavily into an urbanite projection of flyover identity onto rural people,” Ross says. “The fact is, the rural West is not a homogenous place by any means.”

A common thread among Westerners, in Ross’ view, is open-hearted skepticism — a combination of curiosity, independent thinking and compassion.

His time with Ladd sticks out as particularly memorable because it demonstrated what can happen when that skepticism is put into practice. Misunderstanding can become clarity; similarities can overshadow differences.

Ross sees his job as illustrating the value that exists in this misunderstood place with all of its layered beauty, its diverse identities, its silent histories, its cultural worth.

In Niland, California, Ross met Cuervo, a self-proclaimed vagabond in his 60s who wandered the mountains and desert spanning Southern California and northern Mexico with a mule and donkey in tow. He wore a red flannel shirt and a gray kilt, and owned few visible possessions.

“He along with other vagabonds have shown me that the richest lives can be led with the fewest things, that wealth exists in interactions with others, through spontaneity and intimate knowledge of the land,” Ross says. “Through connection, we can find an understanding with others, no matter how different they are, politically or religiously or economically. It just reminds me of the hope in humanity.”

What does it mean to be a person in the West? Ross’ work is still attempting to dissect that, even to find his own answer for himself.

But what he’s gathered so far is that it can mean being overlooked or shrunk down to size to fit a certain mold. It can mean contending with stereotypes and clichés that make it easy to put off putting in the effort to understand the region’s complexity and examine its gray areas.

In the Talking Heads’ 1978 track “The Big Country,” the chorus tells of an airplane passenger’s reaction to looking down on the nation’s sprawling country: “I wouldn’t live there if you paid me, I wouldn’t live like that, no siree, I wouldn’t do the things the way those people do, I wouldn’t live there if you paid me to.”

What if that passenger got to see Ross’ West? Would it change their mind? Would that matter?

Ross believes so, and that debunking the myth of “flyover country” is all the more urgent in our times and all the more rewarding for those who attempt it.

“I think the accumulation of experiences that I’ve had with strangers, people I’ve met along the road, they’ve taught me to arrive in humility and to walk in grace. That one can never underestimate a person, and that there isn’t a place for my own judgment or preconceived notions,” he says. “They’ve shown me the incredible power and promise listening holds. And through that, essentially, they’ve shown me hope.”

This story appears in the May 2024 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.