OAKLAND, Calif. — A lone voice cried out as a thousand black-clad riders spilled from the BART train onto the platform at Coliseum station: Rai-Ders! In a time before COVID-19, the maskless horde called back, droning in a minor key: Rai-Ders! Rai-Ders!

Their chant is the song of Raider Nation, the NFL’s most rabid fan base. For decades, these menacing tones filled the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum and echoed in its aging concourses, through rain and shine, boom and bust, outlasting every brand name that got slapped on the gates. But on this day — Dec. 15, 2019 — it struck a different chord.

The crowd snaked across a pedestrian bridge, passing over decrepit warehouses and pocked backstreets. Everyone wore a jersey, a hat, a T-shirt, a hoodie or some combination bearing the Raiders’ pirate logo. We had all endured years or decades of frustration, as our team failed to “just win, baby.” I know this because I am one of them.

What brought us here on this crisp, clear day was more a funeral than a game. Even as we descended on the last Raiders game in Oakland, our brokenhearted love was unconditional. We marched toward the Coliseum, a concrete hulk shrouded in the smoke rising from vast lots full of cars, trucks and barbecues, and raised the chant again — Rai-Ders! — both mournful and defiant.

A season later, the pandemic is only one reason none of us will be at Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas this Monday night, when the Raiders debut their sleek new digs against the New Orleans Saints on national television. The move and soaring ticket prices have left many fans behind. The financial windfall could help one of the NFL’s most storied but cash-strapped franchises to compete in a sport increasingly shaped by money, but will Raider Nation find purchase in the Intermountain West?

The funeral party

The tailgates stretch to the horizon. All kinds of music thump from cars, trucks and RVs: heavy metal, hip hop, rancheras. Families smoke ribs and grill carne asada. An entire hog roasts on a spit in the aisle. Strangers offer cold drinks and chunks of meat.

“I love this so much,” a man shouts, waving his hands in every direction. Chris is an Oakland native and software engineer who recently moved back after 20 years in Kansas City. There, he’d wear this same black jersey to see the Raiders play at Arrowhead Stadium, a fact that Chiefs fans did not appreciate. “By this time,” he says, grinning, “I’d have been in about three fights.”

Two common misconceptions are quickly dispelled. First, in the eyes of Raider Nation, there is only one “nation.” To claim “Chargers Nation” or “Patriots Nation” or any other such monstrosity is to risk life and limb. Second, Raider Nation is not made up of fans; they’re Raiders, every one, no more and no less than any player who ever donned the silver helmet.

A man with a shaved head and a goatee asks me to shoot a photo of him with his friends. “I know you’re not a Raider,” he says, taking his phone back, “but thank you for coming.” Offended, I point at my clothes, silver and black from head to toe (my John Matuszak jersey is on loan). He shrugs, unimpressed, until I pull a Raiders beanie from my pocket. “My brother, you are a Raider,” he says, embracing me, then whispers, “sorry, bro, we’ve even had — Niner fans show up wearing the colors.”

For the rest of the day, no matter how much I sweat, I keep the beanie where it belongs.

Just as the East Bay has long been San Francisco’s more industrial sibling, the Raiders have always drawn a different crowd. To a Raider, the 49ers are slick, modern and privileged. The Raiders’ outlaw image appeals to populations on the wrong side of the American dream: blue-collar, rough around the edges, often bearing a certain disdain for authority.

It’s not just a logo, either. In their best days, the team played hard both on and off the field, doing whatever it took to win, echoing the swagger of longtime owner Al Davis, whose motto — “Just win, baby” — still resonates. A tough kid from Brooklyn who dressed like a football mob boss, Davis — who first stood up to the NFL as commissioner of the old AFL—famously sued the league for the right to move the Raiders to Los Angeles in 1982. A huge turnout at a preseason game in Oakland convinced him to move back in 1995.

Raider Nation almost relishes believing that the NFL and its referees are against them. The Raiders are consistently one of the league’s most penalized teams. As good as they’ve been— winning three of five trips to the Super Bowl in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 2000 — they’ve borne the brunt of some of the league’s most controversial calls, from the “Immaculate Reception” to the “Tuck Rule.”

A few calls have gone the Raiders’ way, but that’s a story for another day. This day is about saying goodbye. And it’s not just the working class getting left behind.

Sinners and saints

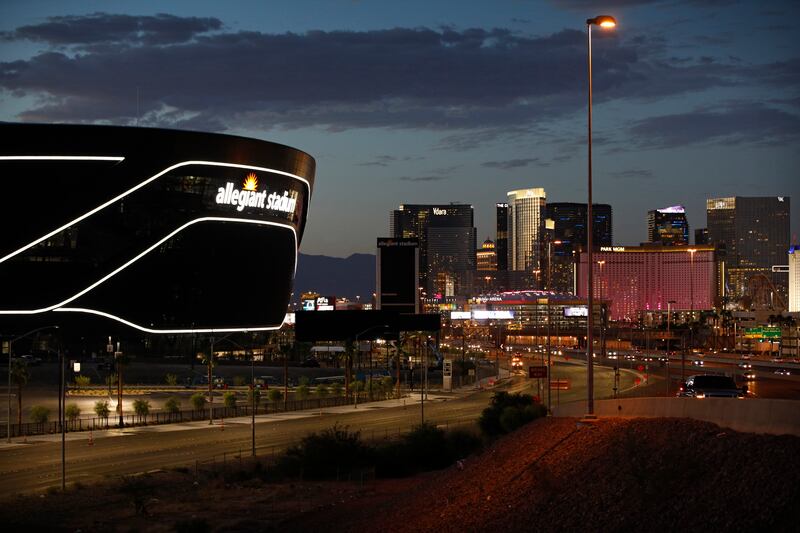

Allegiant Stadium looms over Interstate 15, menacing and beautiful like its cinematic namesake. Inside, it’s a jumble of posh suites, eateries and a monument to Al Davis, with a translucent roof and a retractable grass field that rolls outside for sunlight. Massive lanai doors open onto a view of the strip, where The Killers will play a halftime show on the roof of Caesar’s Palace. Built to make money, it fits right in.

The city was born more humbly. Eight miles north, off the Washington Street exit, 30 pioneers from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints built an adobe fort among the Paiutes at Las Vegas Springs in 1855. Their mission lasted just two years, but others used those buildings as ranchers and railroads brought the valley into the 20th century.

But those pioneers left a legacy. Their successors returned by 1905, founding a branch of the church in 1915, and flourished in the desert. In 1998, Latter-day Saints comprised about 6.6% of the population in Clark County according to UNLV’s Cannon Center for Survey Research, as reported by the Las Vegas Sun. More recent data was not available.

That may not seem like much, but it matters. A former state boxing commissioner, a behind-the-scenes political player, once told me that for most of his career, he couldn’t get anybody elected to state office in Nevada without the Latter-day Saint vote. He courted the approval of local leaders and chose candidates with their values in mind.

Similarly, the Raiders seem ready to reach for the suburbs — and perhaps beyond. The team starts a vocally Christian quarterback in Derek Carr. They jettisoned a third-round draft pick who was a little too entranced by the city’s bright lights, according to The Athletic. And in 2019 they signed Intermountain Healthcare — a medical conglomerate based in Utah — as a sponsor for their training facility in Henderson.

Follow the interstate north, over Mormon Mesa, through the Virgin River Gorge, across two state lines, past booming St. George and a montage of farm country, sprawling subdivisions and majestic ridge lines, until it rolls past the windows of the Deseret News in Salt Lake City. This week, I stared out those windows — wearing my Raiders hat — and wondered who among us will make that drive for a game.

Utah is a no man’s land of NFL fandom —nand perhaps, a sleeping giant. A 2019 poll from UtahPolicy.com found that the Denver Broncos led as the favorite team of just 15% of Utahns who even claimed one. The next 39% were split between the 49ers, Patriots, Seahawks, Packers and Rams. The Raiders didn’t make the list, but now they’re the closest by far.

A Raiders mug sits on my editor’s desk. Another editor whispers his devotion while glancing over his shoulder — the image is not exactly wholesome. He pines for “Big Tent Raiderism,” when the Nation will embrace even white-bread consumers, without so much as a tattoo. He doesn’t realize that’s always been the case.

In 1980, the Raiders drafted a gangly quarterback from Brigham Young University, the first Cougar ever taken in the first round. Marc Wilson never cemented himself as the starter, but he got a fair shot. Because Al Davis never cared where you came from or how you looked.

Under his maverick leadership, the team notched a litany of more significant firsts. Eldridge Dickey was the first black quarterback drafted in the first round. Art Shell was the first black head coach in the modern era. Amy Trask — the “princess of darkness”— was the NFL’s first female executive. And Tom Flores, now a finalist for induction into the Hall of Fame, was the first Hispanic starting quarterback and the first minority head coach to win a Super Bowl.

Ask any Raider: the only colors that matter are silver and black. And tattoos are optional.

An unceremonious goodbye

The farewell started Saturday morning at Ricky’s Sports Theatre & Grill, a dark little tavern in an old San Leandro strip mall where former players and even head coach Jon Gruden are known to drop by. Merch vendors in the parking lot hawked T-shirts that proclaimed: “Loyal to the Soil,” “Forever Oakland,” and “Win, Lose or Tie, Raider till I Die.”

Inside, a tall man with broad shoulders and white hair stepped to the counter, with three huge, shiny rings on his fingers — like Super Bowl rings. He looked like a player, but he set me straight. “I bought these in the parking lot,” he said. “20 bucks for all three.”

But John Ledeboer did play football — at Brigham Young University. He was a tight end in the early 1970s. Gifford Nielsen was his quarterback, LaVell Edwards his coach. He has fond memories of Provo, but his heart has been with the Raiders since they lost to the Packers in Super Bowl II.

Around him, the walls were draped with signed jerseys, posters, footballs, programs, letters, and photos. The tavern was a museum or a tomb, dense with nicknames that would make normal people cringe: The Assassin, Dr. Death, The Mad Stork, The Judge, The Snake.

The old Raiders were brutal on the field and reckless off of it — like the night Matuszak, a bearded, long-haired defensive tackle, got arrested in Livermore after speeding down the freeway shooting at traffic signs from his car, according to quarterback Ken Stabler’s memoir. But they were also part of their community.

Back then, Ledeboer said, a family could afford tickets, and he went to every home game — including the “Heidi Bowl,” an infamous comeback win after NBC gave up on the Raiders and switched to a movie about a little Swiss girl. As a kid, the Walnut Creek native would wait by the locker room to meet his heroes, who’d spend hours signing autographs.

Ledeboer, who now lives in Wenatchee, Washington, still had season tickets in 2019 — eight front-row seats near midfield — but that was about to end. It would cost $75,000 apiece, he said, to transfer his seats to Las Vegas, where game tickets would triple in price, from $150 to $450 per seat. “That’s $600,000 now,” he said, eyes wide, “and a million over 10 years.”

He balked, so the team urged him to keep two seats — still about a quarter-million dollars’ worth over a decade. “I could buy a house for that,” Ledeboer said.

The Raiders did not respond to a request to verify those numbers, but they match the cost of personal seat licenses — which give owners the right to purchase seats for a 30-year period — reported by the Las Vegas Review-Journal in 2018. In January 2019, the Review-Journal reported that the team had lowered PSL rates in one section, while a final phase of PSLs would roll out at $500.

That doesn’t account for the costs of a hotel room in Las Vegas — including the tax that’s paying for the stadium. Raider Nation travels well, but it’s hard to imagine Black Hole types getting anywhere near field level, with any frequency, at those prices.

Still, Ledeboer raised two clenched fists, dripping with fake rings. “Once a Raider, always a Raider,” he said, echoing another team maxim. “Remember, three for 20 bucks.”

The last sendoff

The Coliseum erupted as a Raiders receiver beat the Jaguars defense on a crossing pattern and cut upfield to score the day’s first touchdown. Oakland native Marshawn Lynch, on his second retirement, walked the concourse like a regular guy. Lines formed at concession stands where soda, beer and hot dogs sold for astronomical costs.

I had lucked out on StubHub. My seat was in the third row, adjacent to the Black Hole, the notorious fan section in the south end zone — between characters like “Black Thanos” and what looks like an executioner with skulls dripping from fake shoulder pads, next to a guy in a monkey mask who says he used to date one of the Raiderettes. In short, I’m among the rowdies.

At this range, the field looks smaller, but the players look so much bigger. This is my first Raiders game. I was born and raised over the hills, but when I was old enough to care, the team was in Los Angeles, chasing the same prize they are now.

Because NFL owners share revenue from all other streams, stadium income is the only way to get ahead. It’s even more vital for the Raiders, who aren’t backed by a tech fortune or old family money. Some have speculated that they traded All-Pro defensive end Khalil Mack in 2018 because they lacked the cash to put his contract guarantees in escrow.

Al Davis resisted leaguewide trends toward corporate management and billionaire ownership, even when the clear way forward was to sell the team, or part of it, to finance a stadium. He was a football man whose only known pursuit was the team he ran tirelessly until his dying day in 2011. His obsession was to win. But winning isn’t cheap.

In the Coliseum, the Raiders were playing September home games on the Oakland Athletics’ baseball infield. Other flaws were less charming: the distance from the sidelines to an X-ray machine; the below-sea-level field that got boggy with rain or even fog; the sewage that sometimes seeped into the visitors’ locker room; the ancient porcelain troughs in the men’s bathrooms; the imperfect luxury suites; the utter lack of profitability.

After Al Davis died in 2011, his son, Mark Davis — not a football man, by his own admission — made a new stadium his white whale. He tried and failed in Oakland, then Los Angeles, before landing a deal in Nevada, funded by $750 million in state tax revenue. The gleaming black cylinder now rising above Interstate 15 near the strip — the Death Star, to Raider fans — looks like the fulfillment of his father’s dream.

Today’s NFL is built on corporate clients and luxury boxes, funding an annual salary cap of $198.2 million per team. The average franchise is worth over $3 billion, according to Forbes. In 2015, before Mark Davis started pursuing a new stadium outside of Oakland, Forbes valued the Raiders at $1.43 billion, 31st in a league of 32. This year, Forbes ranked the Raiders 12th, at $3.1 billion, with about $100 million more in annual revenue.

Who will fill the seats? High rollers from the strip? Probably. Tourists? Locals? Utahns? Time will tell, but Mark Davis expects Raider Nation to follow. “There’s no question about it,” he told NBC Sports. “The Raiders and Oakland grew up together. We were the stepchild of San Francisco. We were just Oakland. And I believe my dad took special pride in that and in building it up. The Raiders were born in Oakland, and Oakland will always be part of our DNA.”

The last game in Oakland ended poetically, with a Raiders’ loss after a disputed call. The NFL would apologize, but not before Raider Nation lost its collective mind. They booed the team into the locker room. Ignoring three layers of security and a circle of police, some jumped the rails and were immediately tackled and cuffed as the crowd chanted “let them go.” They threw trash on the field and launched water bottles at the cops. Some ripped drink holders off the seats. Others ripped out the seats instead. “Burn it down,” yelled a woman near me, as a hipster preached about gentrification.

Meanwhile, Black Hole icon Wayne Mabry announced his retirement. A superfan known as The Violator — his face painted in silver-and-black stripes, with spiked shoulder pads — he told the Review-Journal he simply can’t afford to follow the team to Las Vegas. “I understand the business side of it,” he said. “But as a fan, I feel like I’m being evicted. I’m still paying the rent, but they’re selling the property.”

The sendoff was painful but cathartic. A sacrifice for the greater good. Oakland is a memory — as home always is — but the future is promising. PSLs sold out in January, game tickets in May. And the cash flow is starting to show on the field. People ask me, will you still root for the Raiders? And I can’t make sense of the question. Once a Raider, always a Raider.

With any luck, my timid friend will walk the new tailgate in Las Vegas next year. He’ll shy away from the more colorful characters, until some guy with a shaved head sees his jersey, offers a plate piled with steaming carnitas, and say here you go, my brother.