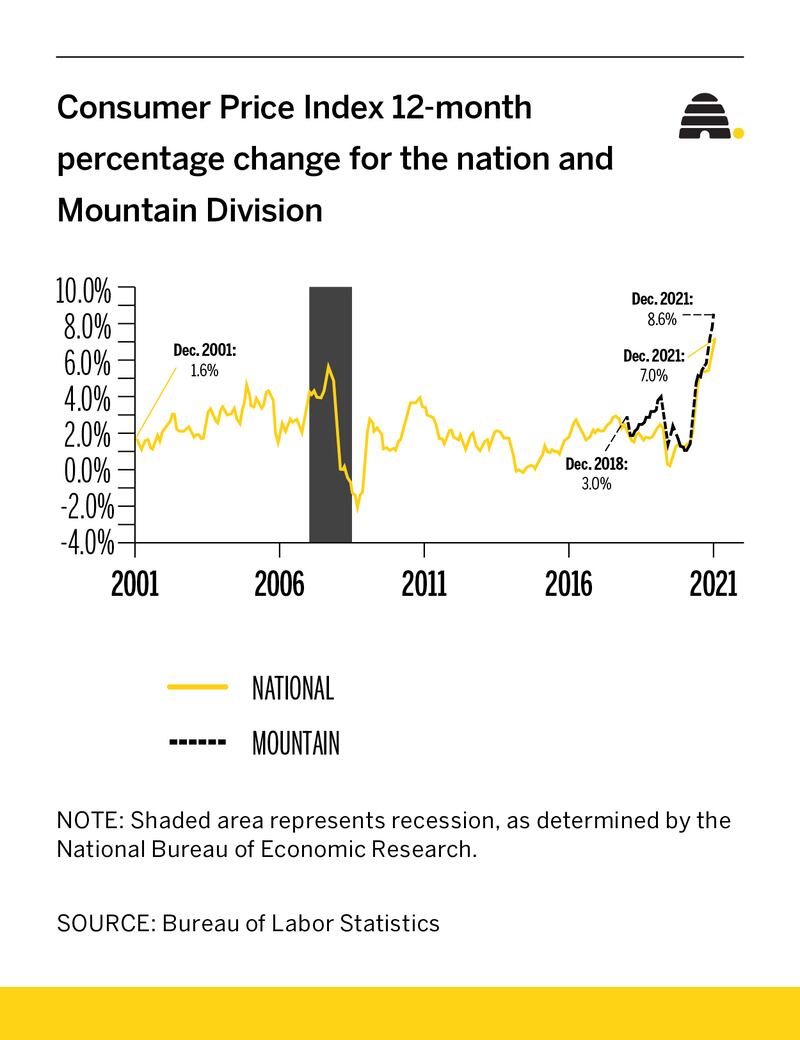

Inflation hit the Intermountain West harder than any other area in the country during 2021, with prices climbing 8.6% compared to the national average of 7% in the 12 months ending in December, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported.

But it would be misleading to conclude that living in Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Colorado and other states east that comprise the bureau’s Mountain-Plains division is more expensive than other regions of the country, a bureau economist said. Gathering data for the division’s Consumer Price Index started in December 2017.

“Comparing (Consumer Price Index) data across regions can be a little deceptive,” warned Julie Percival, a regional economist for the bureau’s Southwest and Mountain-Plains Information Office. For example, she explained, a price increase at the pump in Dallas would reflect a larger percentage increase than the same increase in San Francisco, where gasoline already costs more than it does anywhere in Texas.

But her example of fuel prices is appropriate as it was one area where many people across the West have felt the sting of inflation the past year. In the Mountain-Plains division, motor fuel prices soared 57.5%. Nationally, motor fuel prices increased 49.5% during 2021.

Percival said consumers should keep in mind that gasoline prices had dropped 26% during the previous year.

A recent report by the U.S. Energy Information Administration also explained the motor fuel price increases last year are primarily because of declining refining capacity in the West and Intermountain regions. Motorists consume almost all of the gasoline produced in the two regions, so the closure of refineries in these regions “have reduced refinery output of gasoline, which in turn has lowered inventories and contributed to higher prices,” the agency reported in August.

Another cost consumers frequently experience price changes is food prices, which in the Mountain West bumped up 6.2% in 2021, slightly higher than the 6% reported nationally.

Because energy and food prices are so volatile, economists eliminate those two expenses to determine what they call “core inflation,” which increased 7.3% in the Mountain West and 5.5% nationally.

Percival attributed the increase in core inflation to price rises in housing and to the cost of buying used cars or trucks.

Pandemic-induced migration from densely populated urban areas to more less-populated areas have driven up housing costs in the West, both in purchasing and renting a place to live. But the rising housing costs has its roots in the recession more than a decade ago, the Deseret News reported, which severely contracted the home building industry.

The government’s CPI, however, doesn’t measure home purchasing prices, which historically are stable and difficult to track. Instead, the bureau asks homeowners what they would rent their place for in calculating total housing costs. That rent rose 8% in the Mountain division and 3.8% nationally.

Soaring used car and truck prices have afflicted consumers across the country at about the same levels, rising 37% nationally, and 36% in the Mountain West. News reports have attributed that rise to global supply-chain problems.

“Auto manufacturers have been struggling to obtain parts — particularly computer chips imported from Asia — delaying production of new vehicles and pushing up demand for a finite supply of used ones,” The New York Times reported.

As for the 2022 outlook after the largest jump in inflation in nearly four decades, many economists reportedly expect prices to stabilize as supply-chain issues get resolved and the Federal Reserve raises interest rates. Percival also points to consumer prices incrementally dropping during the last three months of 2021 and that wholesale prices increased just 0.2% in December after rising 1% in November.

Wholesale prices, which the government tracks through its Producer Price Index, are viewed as a leading indicator for future consumer price movements.

But some economists cautioned that the country still has some rough months ahead on the inflation front, according to The Associated Press and The Wall Street Journal.

“Persistent supply disruptions will pin producer prices near record levels in the near term, especially given a rapidly spreading omicron variant that will fan inflation pressures,” Kathy Bosjancic, chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics, told the AP.

“I expect inflation in the range of 3% to 4% this year, but I wouldn’t be surprised by a recession leading to 1% inflation or major geopolitical instability driving the inflation rate above 6%,” wrote Harvard economist Jason Furman in The Wall Street Journal.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell told lawmakers Tuesday that if “inflation persisting at high levels longer than expected, if we have to raise interest rates more over time, we will.”

But don’t expect prices used to calculate core inflation to immediately drop this year.

Omair Sharif, founder of the research firm Inflation Insights, told The New York Times that while annual inflation may plateau at 7%, it takes time for prices to cool down. “It’s just a lot of wood to chop to get down to anything approaching the good old days.”