A government’s decadeslong strategy of snuffing out any type of forest fire is changing course.

The Biden administration announced this week a $50 billion plan to more than double the use of controlled burns and logging to thin out vegetation that has fueled the growing number of catastrophic wildfires, primarily in the West.

“You’re going to have forest fires. The question is how catastrophic do those fires have to be,” Agriculture SecretaryTom Vilsack told The Associated Press. “The time to act is now if we want to ultimately over time change the trajectory of these fires.”

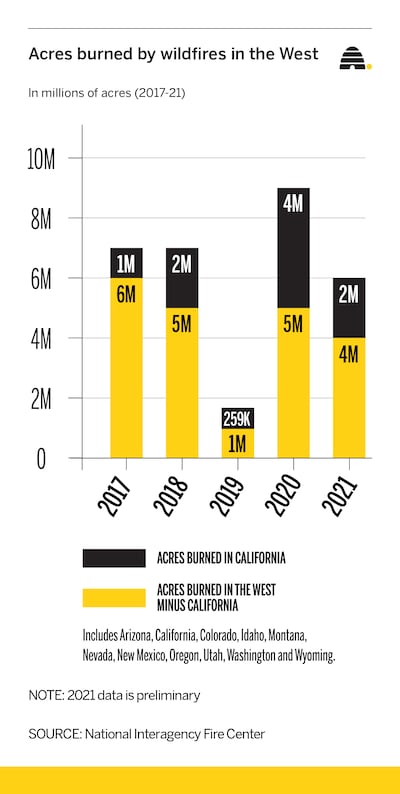

The new approach comes after several years of wildfires becoming larger and more destructive to the forests and nearby communities. A Deseret News analysis of wildfire data on federal land found that over the past five years, more than 113,000 wildfires charred over 30 million acres in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming.

National Interagency Fire Center data shows that about 40% of fires in the West since 2017 were in California, which accounted for more than a quarter of all acres burned on average, killing residents, forcing evacuations, damaging property and spewing air pollutants into other states. Six of the seven largest fires in California occurred in 2020 or 2021, according state records.

The initial focus of the new campaign will be on “hot spots” where development has bumped up against forested areas. They account for just 10% of fire-prone areas in the U.S. but account for 80% of risk to communities because of their population densities and locations.

“We know from a scientific standpoint precisely where this action has to take place in many of these forests in order to protect communities, in order to protect people,” Vilsack said.

Wildfire expert John Abatzoglou, a University of California Merced engineering professor, told the AP that focusing on wildfire hazards closest to communities makes sense.

“Our scorecard for fire should be about lives saved rather than acres that didn’t burn,” he said.

Taming the flames

A warming climate and prolonged drought in the West have dried out the overgrowth of trees and other vegetation, turning forested areas into a tinder box, wildfire experts say. And a study in Australia by Stanford University researchers has shown that controlled fires that thin out the overgrowth reduce the risk of fires burning hotter and out of control.

“Prescribed burns, in combination with thinning of vegetation that allows fire to climb into the tree canopy, have proven effective at reducing wildfire risks,” the university’s Earth Matters magazine reported. “They rarely escape their set boundaries and have ecological benefits that mimic the effects of naturally occurring fires, such as reducing the spread of disease and insects and increasing species diversity.”

Thinning out forests has also proven effective in the West, where the effort was credited with slowing the advance of the Caldor fire last summer that destroyed almost 800 homes and prompted evacuations of tens of thousands of residents and tourists. Oregon’s Bootleg fire last July burned more than 600 square miles but did less damage in forest that was thinned over the past decade.

“We know this works,” Vilsack said. “It’s removing some of the timber, in a very scientific and thoughtful way, so that at the end of the day fires don’t continue to hop from tree top to tree top, but eventually come to ground where we can put them out.”

He acknowledged the new effort will require a “paradigm shift” within the U.S. Forest Service, from preventing any fire to using what some Native Americans call “good fire” on forests and rangeland to prevent even larger blazes.

The aggressive plan that would address some 50 million acres also calls for working with private landowners and Native American tribes both in the highest-risk areas other vulnerable zones. Vilsack added that the Agriculture Department had not paid attention to underserved communities in the past but would make sure they were included this time, according to The New York Times.

The burning West

While forest overgrowth has contributed to the increased intensity of wildfires in the West, other factors include climate change and a historic regional drought. Both factors can be attributed to the longer fire season, as well. A wind-whipped wildfire ripped through a Colorado suburb just last month.

But the primary ignition source of wildfires come from the growing population in the West, according to National Interagency Fire Center data.

Human caused blazes accounting for 62% of wildfires since 2018, scorching more than 12,5 million acres, the Deseret News analysis found. The types of blazes sparked by people range from careless campers and fireworks to communities and power lines in remote areas. A 2021 fire that threatened homes in Utah’s well-traveled Parleys Canyon was ignited by a motorist’s faulty catalytic converter on a car traveling along I-80.

“People are always creating possible sparks, and as the dry season wears on and stuff is drying out more and more, the chance that a spark comes off a person at the wrong time just goes up. And that’s putting aside arson,” Park Williams, a bioclimatologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, told the Times in an article on why California has so many wildfires.

The story noted that seasonal winds are another source of fast spreading fires in California.

While 2020 has been one of the worst fire seasons on record, the state agency Cal Fire said the combined factors will make for another challenging fire season in 2022 in that state and the region.

“While wildfires are a natural part of California’s landscape, the fire season in California and across the West is starting earlier and ending later each year,” the agency’s 2022 outlook stated. “Climate change is considered a key driver of this trend. Warmer spring and summer temperatures, reduced snowpack, and earlier spring snowmelt create longer and more intense dry seasons that increase moisture stress on vegetation and make forests more susceptible to severe wildfire. The length of fire season is estimated to have increased by 75 days across the Sierras and seems to correspond with an increase in the extent of forest fires across the state.”

Here is a look at the number of wildfires and acreage burned on federal land in the West the past five years, according the National Interagency Fire Center data. The 2021 data is preliminary:

Wildfires in the West

| State | Year | Number of fires | Amount of acres burned |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 2017 | 2,321 | 429,564 |

| Arizona | 2018 | 2,000 | 165,356 |

| Arizona | 2019 | 1,869 | 384,942 |

| Arizona | 2020 | 2,524 | 978,568 |

| Arizona | 2021 | 1,773 | 524,428 |

| Arizona total | 10,487 | 2,482,858 | |

| California | 2017 | 9,560 | 1,266,224 |

| California | 2018 | 8,054 | 1,823,153 |

| California | 2019 | 8,194 | 259,148 |

| California | 2020 | 10,431 | 4,092,151 |

| California | 2021 | 9,280 | 2,233,666 |

| California total | 45,519 | 9,674,342 | |

| Colorado | 2017 | 967 | 111,667 |

| Colorado | 2018 | 1,328 | 475,803 |

| Colorado | 2019 | 857 | 40,392 |

| Colorado | 2020 | 1,080 | 625,357 |

| Colorado | 2021 | 1,017 | 48,195 |

| Colorado total | 5,249 | 1,301,414 | |

| Idaho | 2017 | 1,598 | 686,262 |

| Idaho | 2018 | 1,132 | 604,481 |

| Idaho | 2019 | 960 | 284,026 |

| Idaho | 2020 | 944 | 314,352 |

| Idaho | 2021 | 1,332 | 439,600 |

| Idaho total | 5,966 | 2,328,721 | |

| Montana | 2017 | 2,422 | 1,366,498 |

| Montana | 2018 | 1,342 | 97,814 |

| Montana | 2019 | 1,474 | 64,835 |

| Montana | 2020 | 2,433 | 369,633 |

| Montana | 2021 | 2,573 | 747,678 |

| Montana total | 10,244 | 2,646,458 | |

| New Mexico | 2017 | 813 | 141,663 |

| New Mexico | 2018 | 1,334 | 382,345 |

| New Mexico | 2019 | 859 | 79,887 |

| New Mexico | 2020 | 1,018 | 109,513 |

| New Mexico | 2021 | 672 | 123,792 |

| New Mexico total | 4,696 | 837,199 | |

| Nevada | 2017 | 768 | 1,329,289 |

| Nevada | 2018 | 649 | 1,001,966 |

| Nevada | 2019 | 562 | 82,282 |

| Nevada | 2020 | 770 | 259,275 |

| Nevada | 2021 | 565 | 123,427 |

| Nevada total | 3,314 | 2,796,239 | |

| Oregon | 2017 | 2,049 | 714,520 |

| Oregon | 2018 | 2,019 | 897,263 |

| Oregon | 2019 | 2,293 | 79,732 |

| Oregon | 2020 | 2,215 | 1,141,613 |

| Oregon | 2021 | 2,202 | 828,777 |

| Oregon total | 10,778 | 3,661,904 | |

| Utah | 2017 | 1,166 | 249,829 |

| Utah | 2018 | 1,333 | 438,983 |

| Utah | 2019 | 1,025 | 92,380 |

| Utah | 2020 | 1,493 | 329,735 |

| Utah | 2021 | 1,085 | 60,863 |

| Utah total | 6,102 | 1,171,790 | |

| Washington | 2017 | 1,346 | 404,223 |

| Washington | 2018 | 1,743 | 438,834 |

| Washington | 2019 | 1,394 | 169,742 |

| Washington | 2020 | 1,646 | 842,370 |

| Washington | 2021 | 1,863 | 674,222 |

| Washington total | 7,992 | 2,529,391 | |

| Wyoming | 2017 | 599 | 90,115 |

| Wyoming | 2018 | 611 | 279,243 |

| Wyoming | 2019 | 486 | 41,857 |

| Wyoming | 2020 | 828 | 339,783 |

| Wyoming | 2021 | 540 | 53,496 |

| Wyoming total | 3,064 | 804,493 | |

| Grand total | 113,411 | 30,234,809 |

Contributing: K. Sophie Will