A recent study has found that rapidly growing communities near forests and wooded areas in the West also happen to be in newly identified “double-hazard” zones for wildfires, shedding more light on why wildfires in the past several years have been so destructive and how to slow that trend.

Researchers found certain vegetation and soils withstand wildfires better than others and the natural distribution of drought-sensitive trees, shrubs and grasses throughout the West amplify the effects of climate change creating double-hazard zones for wildfires in specific areas of the western United States.

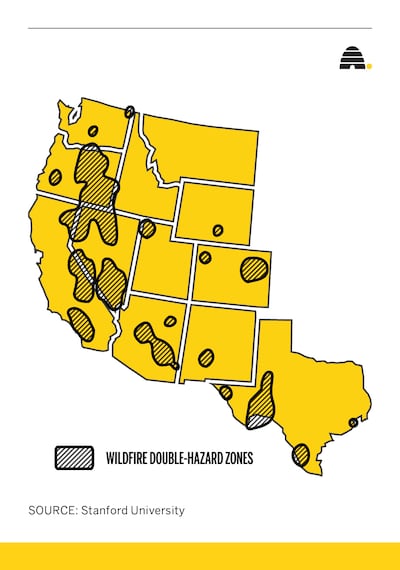

Their research identified 18 double-hazard zones mainly concentrated in eastern Oregon, Nevada’s Great Basin, central Arizona’s Mogollon Rim and California’s southern Sierra Nevadas. Sizable zones were also identified in Colorado and Texas.

The findings published this week in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution come on the heels of the Biden administration announcing a 10-year $50 billion investment in controlled burning, vegetation thinning and other efforts to tame the increasing threat of wildfires to communities in 11 western states.

“California and other western states are working hard to figure out how to adapt to the changing wildfire risk landscape, including long-term decisions around issues such as land use, vegetation management, disaster planning and insurance,” said study co-author Noah Diffenbaugh, a professor and senior fellow at Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment. “There’s a wealth of information in this analysis to support decisions about how to more effectively manage the risks of living in the West in the context of a changing climate.”

Researchers set out to test the hypothesis that climate change is increasing the wildfire hazard uniformly across the West. “I asked, is that true everywhere, all the time, for all the different kinds of vegetation? Our research shows it is not,” said lead author Krishna Rao, a doctoral student at Stanford University.

Rao and other researchers looked at the “vapor pressure deficit,” which is an indicator of how much moisture the air can suck out of soil and plants, across the region. Vapor pressure deficit has increased over the past 40 years across most of the American West, largely because warmer air can hold more water.

The study suggests the vapor pressure deficit is rising fastest in areas where plants are especially prone to drying out. “The combination of highly sensitive, tinder-dry plants and a faster-than-average increase in atmospheric dryness creates what the authors call ‘double-hazard’ zones,” explained a Stanford University news release about the findings.

The researchers penned an article on theconversation.com, explaining how they compared their map of where vegetation is creating the highest fire risks across the western United States with maps of where people have been moving into the region’s wildland-urban interface.

The interface is where populations live on periphery of undeveloped wilderness.

“We were surprised to discover that the fastest rate of population growth by far has been in the areas with the highest fire risk,” the researchers wrote. “This includes several areas in California, Oregon, Washington and Texas.”

Between 1990 and 2010, an estimated 1.5 million people moved into the high-hazard areas of the wildland-urban interface, which is 50% faster than the West’s wildland-urban interface overall, the study found.

A Deseret News analysis of wildfire data on federal land found that over the past five years, more than 113,000 wildfires charred over 30 million acres in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming. The data also show that people ignite the vast majority of the fires that have torched the abundant vegetation and threatened human lives and structures nestled among flammable trees, shrubs and grasses in the West.

The researchers acknowledged they don’t know what has caused the population boom in the newly defined double-hazard areas. They suggested building codes, timber-dependent communities and people seeking homes surrounded by forests may have contributed to the region’s expansion of the wildland-urban interface. They also noted that a lack of affordable housing has pushed people farther from cities and “may be encouraging more development in the wildland-urban interface, including high-risk areas that hadn’t previously been developed.”

The initial focus of the Biden administration’s effort to combat the growing threat of wildfires will be on areas where development has bumped up against forested areas.

The Stanford researchers suggested their findings be used to identify those hot spots and that community leaders and property owners living there take action to protect their communities through land-use planning, evacuation plans and retrofitting existing structures against wildfires.