After experiencing record traffic fatalities during the pandemic, states in the West and across the country have access to billions of dollars from roadway safety programs through new federal infrastructure funding.

States and localities can tap into $15 billion in formula funding to improve road safety as part of the Transportation Department’s strategy to stem record increases in road fatalities through its “safe system” approach, which “promotes better road design, lower speed limits and more car safety regulations,” according to The Associated Press.

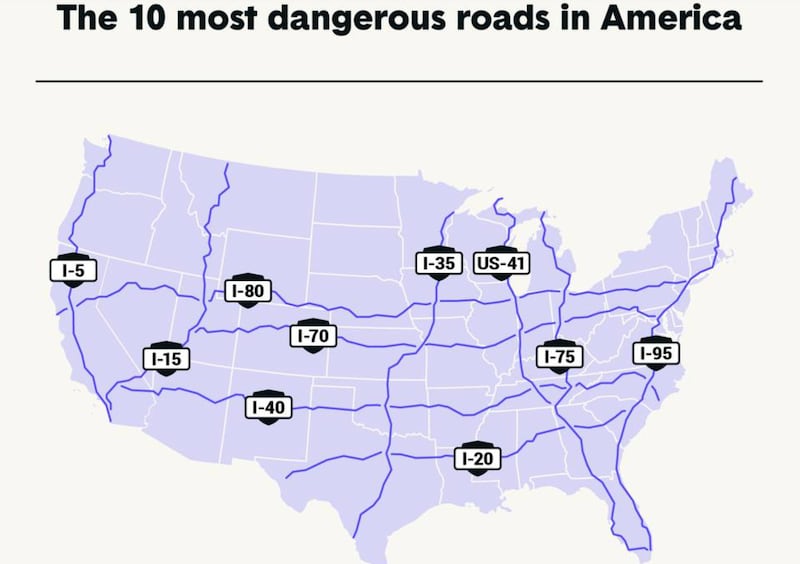

Several states in the West are among those that have experienced rising traffic fatalities. A recent analysis by insurance website thezebra.com of federal data on roadway deaths identified the nation’s 10 most dangerous highways. Five are in the West, and three of those pass through Utah.

The Zebra analysis found Wyoming, New Mexico and South Carolina had the most vehicular crashes per 100,000 people.

In Utah, last year was the deadliest since 2002 on state and local roads. Washington state and New Mexico also recorded record increases in traffic and pedestrian deaths, according to a pair of reports in The New York Times published shortly after the release of the Biden administration’s safety guidelines. A Times analysis of federal data showed 17.5% from the summer of 2019 to last summer was the largest two-year increase since just after World War II.

And traffic fatalities have also captured recent headlines in Nevada, where a man driving 65 mph over the limit slammed into a minivan, killing himself and eight others in North Las Vegas. It was reportedly the deadliest crash on Nevada roadways in at least three decades.

Speeding is leading cause of traffic deaths. More than 1 in 4 traffic fatalities occur in speed-related crashes, the AP reported, citing government data.

And the government is urging states to consider spending share of their federal money on speed cameras as a proven enforcement tool against hazardous driving.

“Automated speed enforcement, if deployed equitably and applied appropriately to roads with the greatest risk of harm due to speeding, can provide significant safety benefits and save lives,” according to the Transportation Department’s safety strategy released last week.

But the technology is not popular. Only 16 states — Alabama, Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee and Washington — and the District of Columbia currently have speed camera programs in place, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Six states — Maine, Mississippi, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Texas and West Virginia —prohibit both red-light and speed cameras. Montana and South Dakota prohibit red-light cameras, and New Jersey and Wisconsin do not allow speed cameras. Nevada prohibits the use of cameras unless operated by an officer or installed in a law enforcement vehicle or facility.

The conference also noted that opponents have challenged the constitutionality of automated enforcement laws in many jurisdictions. Missouri’s Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that red-light and speed cameras were unconstitutional.

In the 1990s, Utah’s Legislature banned the use of what was then dubbed “PhotoCop” that caught driver’s running red lights. An attempt by city leaders to repeal the ban in 2005 never made it out of committee.

While local leaders, law enforcement and some residents argued at the time that the technology would save lives, opponents won the day by framing the issue around personal liberty.

“This country was founded on freedom and liberty, this country was not founded for safety or security,” testified Salt Lake resident Dalane England. “People are going to die if we drive automobiles.”

Those arguments may surface again as states and localities decide how they want to use their share of funding set aside for road safety measures. The AP reported that states have the option to use up to 10% of the $15.6 billion in total highway safety money available over five years for specified noninfrastructure programs, such as public awareness campaigns, automated enforcement of traffic safety laws and measures to protect children walking and bicycling to school.

Federal guidance also requires at least 15% of a state’s highway safety improvement program funding targets pedestrians, bicyclists and other nonmotorized road users if those groups make up 15% or more of the state’s crash fatalities.

And the issue is already becoming politicized.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis criticized Biden’s infrastructure bill at a recent press event, singling out speed cameras as an example of unwanted waste.

“Like we need more surveillance in our society right now,” he said.