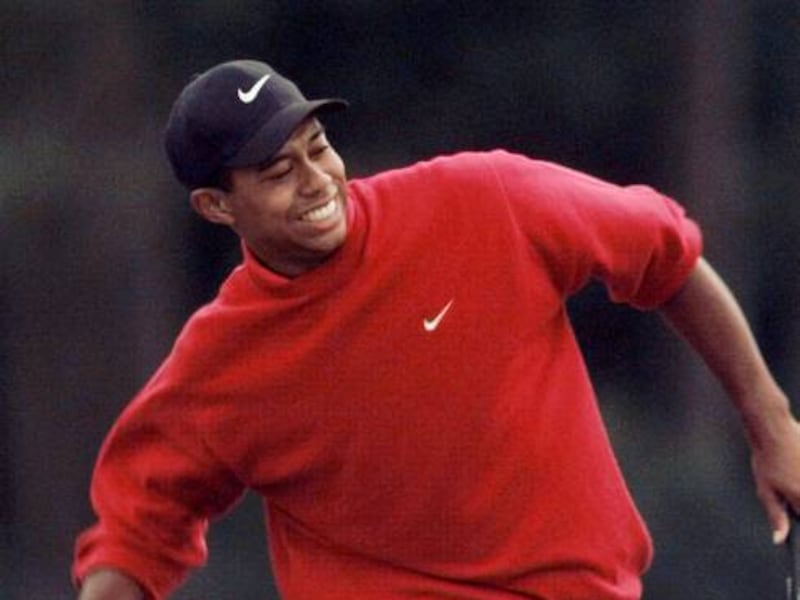

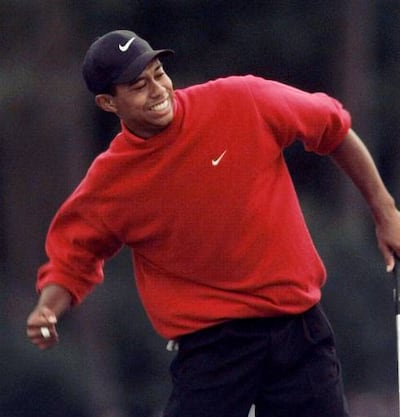

SALT LAKE CITY — In the spring of 1997, when he was 7 years old, Tony Finau sat on the couch in his family’s apartment in Rose Park on the west side of Salt Lake City transfixed by what he was seeing on TV: a 21-year-old black kid named Tiger Woods dismantling the field at the Masters.

He had never watched a golf tournament before, but this one had him mesmerized. “I saw this kid who was the same color as me,” remembers Finau. “I saw him fist pumping, I saw him wearing the green jacket; he made the game look so cool. I looked at it and I’m like, man, maybe I can do that someday, maybe I can play in the Masters.”

Fortunately, no one was there to tell him he should have his head examined.

There were just so many reasons why not.

On any number of levels it didn’t add up: Culturally — Tongans don’t play golf, they play football. Socially — the other kids in Rose Park: you’re doing what?! And especially financially — Kelepi Finau made $35,000 as a baggage handler at the airport, which had to support a family of nine. There wasn’t enough left over for a bucket of balls on the driving range, forget about greens fees.

There was also the problem that the person who was going to teach Tony how to play golf did not play golf.

The boy really only had two things going for him. One, his brother Gipper, 11 months younger, had already taken up the game and was way better than Tony; and two, his dad Kelepi, the aforementioned golf coach, didn’t believe in just urging his boys to dream, he believed in urging them to dream outrageously.

Wait, make that three things. Three, Tony’s mother. It was Ravena Finau who told her husband she wanted him to come up with something her Irish twins could do together that would keep them occupied and out of trouble in a place that had its share of gangs and temptations.

Thus instructed, Kelepi thought, well, all right, and got to work, figuring out how to do golf on the extreme cheap.

He bought clubs at Deseret Industries and the Salvation Army for 75 cents apiece and cut them down to junior size. He checked a copy of “Golf My Way” by Jack Nicklaus out of the library and that became his instruction bible. He went to the municipal course down the street and after realizing there was no way he could afford to do anything that cost money, discovered that anybody could pitch and putt on the practice green for free.

He went home, collected a bunch of golf balls from neighbors who’d heard what he was up to, backed the car out of the garage, and put up a mattress on the wall that the boys could hit into off strips of carpet he placed on the floor.

The Finau Country Club was open for business.

• • •

Kelepi Finau was 11 years old when his father brought his family of 10 from the shores of Tonga to the shores of Los Angeles. It was January 1974. They moved into a tiny house in Inglewood. Sione Tonga Finau, who is 92 and still going strong in Inglewood, mowed lawns and took care of people’s yards, never letting his children forget that he’d brought them to the land of opportunity and now it was up to them what they did with it.

Remembers Kelepi, “Before we came here, my mother and father sat us down in Tonga and said look, this country is the greatest country in the world, it will offer you things others won’t, it will recognize your talent, it will recognize your hard work, but if we go there and you kids don’t have gratitude in your hearts for stepping foot in that country, I don’t think any of you will be successful.”

Kelepi met Ravena through sports. They were teammates on a coed volleyball team that traveled to tournaments around Southern California. Vena’s parents — her mother was Tongan, her father Samoan — met when they were students and volleyball players at BYU-Hawaii. She was born in America and, like her parents, attended and played volleyball at BYU-Hawaii.

Kelepi and Vena were married in 1985 in Long Beach and settled into Southern California. When Kelepi’s employer, Delta Airlines, merged with Salt Lake City-based Western Airlines, an opportunity came to relocate to Utah. The weather wouldn’t be as warm, but the cost of living was lower — and there was a tight-knit Tongan community there, many of whom the Finaus were either related to or shared the same LDS faith.

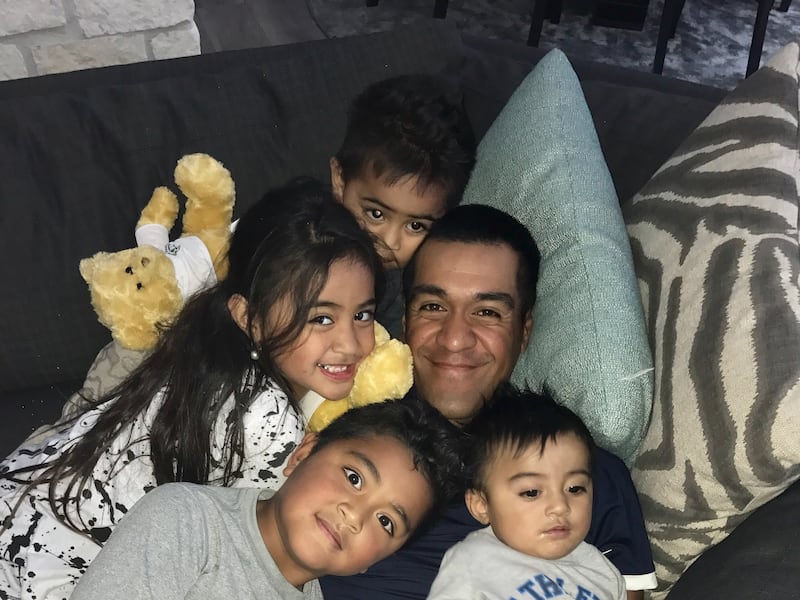

They made the move with their two oldest children in early 1989. Later that year, in September, Tony was born. The following August, Kelepi Jr., who everybody called Gipper, came along.

Kelepi remembers his wife’s words just before Gipper was born: “She was lying in labor at the hospital and she grabbed me and said, ‘You know, in no time, him and Tony’s going to be like twins, whatever one’s going to do the other’s going to follow. I’m going to need you to have a project with these two, because if they get into trouble and give me problems, I’m going to shoot you myself.’”

• • •

“I didn’t know until I was 15 or 16 years old my dad had no clue what he was doing,” says Tony. It’s a line he delivers often now that he’s one of the world’s top golfers, guaranteed to bring smiles, even from his dad, especially from his dad, whose only real contact with golf prior to starting Team Finau was one time when Delta sent the baggage handlers to represent the airline at a scramble tournament.

But if, when it came to dissecting the golf swing, Kelepi Finau was no Butch Harmon, or even Earl Woods, what he was — after playing almost everything except golf — was a natural-born coach.

“This whole golf thing was so left field for us, as Polynesians, but he had a lot of knowledge about sports in general,” says Tony. “My dad was a genius really, he was an absolute genius.”

Kelepi the coach had three rules for his team of two, which he wrote on a sign he hung in the garage: 1. Listen. 2. Be Serious. 3. Don’t Quit. On other signs he wrote motivational phrases. One of them pretty much summed up the whole enterprise: “If you didn’t know any better, you’re better off.”

Not knowing any better worked out brilliantly for Team Finau. The fact that they couldn’t afford greens fees was a huge blessing in disguise. It taught them to learn to chip and putt before anything else.

“We hit thousands upon thousands of chips, maybe millions,” says Tony. “We learned what it was like to make the right sound when you make a solid chip.”

This first took place at the Jordan River par-3 course on Redwood Road just a few blocks from the Finaus' apartment. (The course has since reverted to its original purpose: a Frisbee golf course).

Tony and Gipper became such fixtures at the course that the golf pro, Richard Mason, started letting them play for free in the late afternoons. “Once he saw how serious we were, he would be like, ‘OK, you guys go ahead and have at it,’” says Tony. “I’ll never forget him for that. There’s no way we’d have ever learned how to play the game if not for that golf course. Once he allowed us to just play, we would average four or five times playing the nine-hole par 3.”

Another unexpected bonus: the Jordan River’s short holes featured small, elevated greens, calling for accuracy and finesse more than strength and power. In “Golf My Way,” Nicklaus suggested that the game should first be learned from 100 yards in. Kelepi’s boys were doing just that.

What became the Finau brothers’ calling card — eye-popping drives — came later, a byproduct of that beginning.

“The crazy thing is, the last club I ever learned to hit was my driver,” says Tony, who consistently ranks among the top hitters on the PGA Tour with drives that average more than 320 yards. “My brother and I ended up being known for our distance, but we had no idea how far we could hit the ball because we hit it the same and all of a sudden we’re going to tournaments and we’re driving the par-4s. At 10 years old, I was hitting it like 240.”

Gipper was the original prodigy. His year’s head start showed in the first tournament the brothers entered together. It was a junior event at the Jordan River course in August 1997.

Six-year-old Gipper shot par and won the tournament in a playoff against two 10-year-olds. Seven-year-old Tony finished back in the pack with a 47 — 20 strokes behind his little brother.

Meanwhile, the other kids in Rose Park looked at the Finaus and scratched their heads. Didn’t they know football ran in their genes? Just down the street were their cousins Haloti Ngata and Sione Pouha, who would make it to the NFL. Stanley Havili, another relative, got a football scholarship to USC. Yet another cousin, Jabari Parker, who grew up in Chicago, would wind up in the NBA.

But golf was it and soon enough, the Finaus were the talk of Utah junior golf. To the point that when it came time for Tony to enter high school, East High let it be known he would be more than welcome to be part of their golf program that had won two straight big-school state championships.

Tony liked the idea. So did Kelepi. But Vena didn’t. The Finaus lived in West High School’s boundaries, not East’s. What kind of message would it say about loyalty if they abandoned their own?

So Tony went to a high school that didn’t even have a golf team. A year later, Gipper followed. A year after that, with a coach who didn’t play golf (familiar ground for the Finaus), West High, Salt Lake City’s oldest high school, won its first state golf championship in 114 years.

The next summer, Tony won the Utah State Amateur at 16. (Not to be outdone, at 16, Gipper played in Utah’s Nationwide Tour (now Web.com) event and made the cut, the third youngest ever to do so).

The day Tony graduated from high school, he turned professional. He was 17 years old. He had scholarship offers to play college golf, Stanford and BYU among them (Weber State and Utah State were also interested in having him play basketball), but when a local businessman offered to put up $50,000 apiece to stake Tony and his brother in a made-for-TV golf event in Las Vegas with a $2 million payday to the winner, they jumped at the chance. Tony made it to the final round and collected $100,000 and a Callaway sponsorship deal — enough to pay back his benefactor and get him started on his quest to make it to the PGA Tour.

No one could say he didn’t pay his dues. Every year from 2007 through 2011, he went to the PGA Tour’s grueling qualifying school. Every year he failed to make it out of the second round. He toiled on the eGolf Tour, the Canadian Tour, the Gateway Tour — golf’s low minor leagues.

Then in November 2011, real tragedy struck. Driving home from a wedding in Reno, Vena died in a car accident at 47. About to get married, scraping to make ends meet, mourning his mother, Tony developed a stomach ulcer from the stress and had to be hospitalized. He couldn’t walk for five weeks, couldn’t swing a golf club for eight.

Contemplating his future without the mother who was his rock, he decided the one thing she absolutely would want him to do was to keep going, to not quit. The first mini-tour event he entered after the eight-week layoff he won. He won the next one, too. He started a tradition of wearing a green shirt in the final round on Sundays as a tribute to his mother. It was her favorite color. “I know she’s there, I know she’s following me,” he says.

The next year, in 2013, he finally made it through qualifying school, gaining full-time entry on the Web.com Tour, just one step below the big time. In 2014, not long after Utahn Boyd Summerhays became his swing coach, he won the Web.com’s Stonebrae Classic to qualify for the 2014-15 PGA Tour — the first person of Tongan or Samoan descent ever to do so. (Gipper, who at 27 hasn’t given up on getting there, could be the second).

In his rookie season on the top tour, Tony had five top-10s in 31 starts and banked $2.1 million. In 2016, he won another $1.8 million in 28 starts and got his first PGA Tour victory at the Puerto Rico Open. In 2017, he broke through with $2.8 million and by making it to the FedEx Cup finals at year’s end earned automatic qualification for all four majors in 2018.

Already this season he’s had two second-place finishes and has won more than $2 million. In less than four years he’s made $9 million in prize money and is ranked No. 34 in the world.

All that, and when Golf Digest recently released its list of “The Top 30 Nice Guys of the PGA Tour” — after polling players, caddies, media members, golf officials and industry insiders — Tony came in No. 2, behind only Jordan Spieth.

Kelepi lays that all on Vena. “My kids’ attitude is that no one is a bad person, because that’s how their mom was,” he says. “She greeted everybody, everybody was welcome. They never heard their mom talk bad about anyone. They learned a lot from her teaching them how to be respectful.”

In 2016, while playing at the PGA Tour stop in Fort Worth, Texas, one of Tony’s drives hit a spectator on the head, causing her to need stitches. After the round, he found out who the young woman was and showed up at her parents’ house with flowers, chocolates and a get-well card. The photo she posted on Instagram thanked him and ended with, “your new favorite fan, Elisa #iforgiveyou #ouch #classact.”

On a larger, longer-lasting nice-guy scale, there’s the Tony Finau Foundation, funded by a percentage of Tony’s winnings that go toward helping underprivileged kids in Rose Park. Each year, Tony visits the six elementary schools in his old 'hood, featuring himself as a 6-foot-4 show-and-tell. He shows a three-minute clip that details his career and accomplishments accompanied by cool, inspiring music, then he talks to the kids.

“I knew when I got on tour that if I had the opportunity to give back to my community, which is Rose Park, I would,” says Tony. “I grew up with a lot of friends that were abused, who dealt with drugs, alcohol, gangs, single parents, no parents, so I know what it can be like. To be a role model for some of these kids, to tell them they can make it, I love that. I tell them where I’m from and I was literally sitting in their chairs and they look at me like I’m Superman and they can believe it because I look like them, I talk like them, I came from exactly where they came from. They can know that you don’t have to come up from a lot. Your dreams aren’t as far as you think.”

• • •

Which brings us to the Masters.

On April 5, at 28, Finau will tee it up in the tournament that got him off the couch as a 7-year-old watching Tiger Woods.

Later on, as he learned the history of the sport and began to appreciate the significance of the world’s most prestigious tournament, he vowed he would not set foot in golf’s mecca until he made the field.

Last November, right after his top-30 FedEx Cup finish secured his place in the 2018 Masters, he flew to Georgia and played his first practice round at Augusta. He was joined by a member of the club, which is required, his good friend Dave Layton and, to round out the foursome, his father.

Kelepi plays golf only sparingly. But no way was he going to pass this up. “It was like a different spirit there, special,” he says. Afterward, “I told Tony, ‘OK, I played Augusta. I don’t think I’m going to play golf for a very long time.’”

“It was an incredible experience,” says Tony, who liked the way the course suits his game. “It’s a big golf course, you can hit it high into the greens. I think it’s a good setup for me. You’ve got to have the whole game, you need to be able to chip and putt. I like everything about it. I wear green on Sunday because it’s my mom’s favorite color, but green goes pretty well on Sunday at the Masters, too.

“I’d be lying if I didn’t say that’s probably the one tournament I want to win,” he adds with the air of a man who hasn’t arrived but is just getting started. “When I started to play golf, I didn’t dream of just playing in the Masters, I dreamed of winning it. I have my first opportunity in 2018.”