Coach Eyestone does uniquely well maximizing talent. He takes kids who weren’t that great in high school and turns them into national-class runners. – Jon Kotter

In some ways, BYU and Ed Eyestone, the Cougars’ guitar-playing track and cross-country coach, has come full circle. When he left BYU, the school’s distance-running prowess went with him; when he returned 15 years later, so did their prowess. It’s that simple.

Like the rest of the country, BYU fans focus on basketball and football fortunes, but success in those sports pales in comparison with the Cougars’ running feats, and Eyestone has been a big part of it as an athlete and coach. For 35 years he has been a major figure in distance running, first at Bonneville High, then at BYU, then as a professional and Olympic road racer. He has been everywhere for running, as an athlete, TV color analyst, magazine columnist and coach.

For his latest act, he has been restoring BYU as a runner’s mecca. Distance running — and endurance sports in general — seems ideally suited to the Mormon culture, with its strictures on alcohol and tobacco and its roots in hardy pioneer stock who, like distance runners, persisted in the face of mental and physical discomfort.

“Abstaining from alcohol and tobacco is certainly not a bad thing in terms of cardiovascular improvement,” Eyestone notes. “And the whole culture of setting goals and working hard toward them and believing there is a divine hand helping guide you to become the best you can be.

"Not that we have a corner on the market by any means, but as we do our part we believe we have a loving Heavenly Father out there to help us do our best, whether that means win, place or show, and that’s a comfortable psychological advantage when you go into competition. It helps with the stress. Whatever happens, it’s going to be OK.”

Over a 40-year period, BYU collected 150 All-America citations in distance running, many of them under the gentle guidance of Clarence Robison and Sherald James. In the ’80s, BYU distance runners gained national prominence. Magazines dispatched reporters to Provo to do in-depth articles to see how they were doing it. “The Stormin’ Mormons," one magazine called them. In the 1984 U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials in Los Angeles, BYU alumni Henry Marsh, Doug Padilla and Paul Cummings swept the three distance races just two weeks after Eyestone won the 10,000-meter run at the NCAA championships. A year later, Eyestone became the third man to claim the collegiate triple crown, winning NCAA championships in cross-country and the 5,000- and 10,000-meter runs on the track while setting a long-standing collegiate record in the latter.

And then the Cougars quietly faded from the scene. They still produced the occasional star — Olympic miler Jason Pyrah, for one — but they were no longer a national force — that is, until Eyestone returned. Consider this: From the time Eyestone graduated in 1985 until he was hired as a coach in 2000 — 14 years later — BYU produced 19 All-Americans in the distance races (track and cross-country). In the nearly 14 years since Eyestone was hired as a coach, BYU has produced 62 All-American citations in distance running (track and cross-country), including five national champions — Miles Batty, Kyle Perry, Josh McAdams, Josh Rohatinsky and a distance medley relay team.

After qualifying for the NCAA cross-country championships only four times the previous 14 years, the Cougars have qualified all 14 years under Eyestone, including team finishes of fourth, sixth and fourth the last three years, respectively. Since 2000, only four cross-country programs have qualified for the NCAAs every season — Colorado, Stanford, Wisconsin and BYU.

This weekend, the Cougars will compete in the NCAA West Region track championships in Fayetteville, Arkansas. BYU’s male athletes have achieved 32 qualifying marks — second most in the country — 15 of them in distance and middle-distance events.

“Coach Eyestone does uniquely well maximizing talent,” says Jon Kotter, a walk-on who was cut twice before making the team and going on to become one of the school’s fastest at 10,000 meters. “He takes kids who weren’t that great in high school and turns them into national-class runners.”

Undoubtedly such success led to a promotion last summer. After years of mulling the change, BYU athletic director Tom Holmoe, a former NFL player who is also a knowledgeable track fan, restructured the entire track and field program. He combined the men’s and women’s programs and appointed Eyestone as director of track and field, which means he will oversee the entire track program while also continuing to coach male distance runners. Other schools have combined their programs, largely because it has at least one advantage. Separate men’s and women’s teams are limited to three full-time coaches to cover sprints, distance running, hurdles, relays, jumping and throwing events. With the programs combined, they have six coaches who will work with both men and women.

Certainly the Eyestone name will carry some cachet for the team, which will aid recruiting. “Ed Eyestone is kind of a legend in running because he was so good for so long,” says Bob Wood, Eyestone’s former agent who has been a behind-the-scenes force in running circles for decades. “You say his name and almost everyone knows that one.”

Eyestone comes from an accomplished, educated and bright family. His parents, Bob and Virginia, earned post-graduate degrees. So did all five of their children, who excelled in school and won scholarships for writing, music, drama and athletics. As noted in the book, “Trials and Triumphs,” the Eyestone children went on to become singers, architects, actors, writers, musicians, beauty queens and runners.

The Eyestone name is the literal translation of the original German name “Augenstein.” Virginia’s ancestors were Mormon pioneers. Eyestone explains it as only a runner would: “My mom’s side all hoofed it across the plains. Most notably, Edward Shields Reid, who was born in Wales and came across the plains in 1861 at the age of 2, much of it astride his father Edward Reid’s shoulders. Apparently, the Reids are known for their endurance.”

Eyestone began running at the age of 13 in 1974 and, except for a two-year break he took to serve an LDS Church mission in Portugal, he didn’t stop racing until 2000, at the age of 39. Think of the mileage he has put on those legs: He averaged 60-70 miles a week in high school, 80-90 miles a week in college and 100 miles a week as a professional, taking only about three weeks off annually. That adds up to nearly 100,000 miles, not counting the less-intense training he did in junior high. If he had run in a straight line, he would have circled the earth four times.

There were 10 All-American citations, four NCAA championships, two Olympic berths, one world track championship, nine World Cross Country Championships and an American collegiate record for 10,000 meters. He was five times the U.S. Road Racer of the Year. He ranked among the top American marathoners for nine years and among the top 10,000-meter runners for eight. He won many of the nation's biggest road races — Bay to Breakers in San Francisco, Peach Tree in Atlanta, Lilac Bloomsday in Spokane and the Twin Cities Marathon. He was second in the Chicago Marathon, second in the Olympic trials marathon (twice), second in Bay to Breakers. He ran in virtually every country in Europe, as well as cities in Australia, the Far East, Russia, South America and Central America.

He competed professionally for about 15 years, running at a top level until he was nearly 40, a remarkable feat given the pounding a distance runner’s body takes. He had a shoe contract with Reebok that provided the financial stability to pursue the sport professionally and pick his races judiciously, which probably helped him remain healthy and prolong his career.

“I stretched it out for a while,” he says. “It was my life. I’ve never faulted anyone for competing past their prime. So what? If you can still do something better than 99 percent of the population, do it.”

When the time came to transition to another profession, he was ready. He had begun preparing for a move to coaching while still in college by studying training techniques. “I saw the impact that Coach (Clarence) Robison had and the good things he was able to do as a coach,” says Eyestone. “I knew that was something I wanted to do.”

He won an NCAA post-graduate scholarship and the NCAA Top Six Award, another scholarship awarded to the top six scholar athletes. He used the scholarships to earn a master’s degree in exercise science, augmenting the knowledge he was collecting as an athlete to prepare for coaching. Throughout his running career, he picked the brains of coaches and runners for training information, not only to aid his own training, but to aid his coaching career.

“He still does that,” says All-American Jared Ward. “I’ve watched him talk to other coaches and I’ve seen a lot of coaches talking to him. He is one who gleans everything he can from others, but he’s also willing to give to everyone as well.”

Eyestone had the advantage of training under highly successful coaches — Robison, James and Pat Shane. In the latter stages of his running career, he took his first coaching job as an assistant at Weber State under Chick Hislop, another masterful distance coach, before being hired 2½ years later as BYU’s head coach for cross-country and distance coach for track and field. Then last summer he was appointed to oversee the entire track and field program as well as men’s cross-country.

“One of my strengths is helping athletes define goals they are capable of accomplishing and helping them establish traditions that reinforce the attainment of those goals,” says Eyestone. “Ultimately, that’s why I’ve been put in this position.”

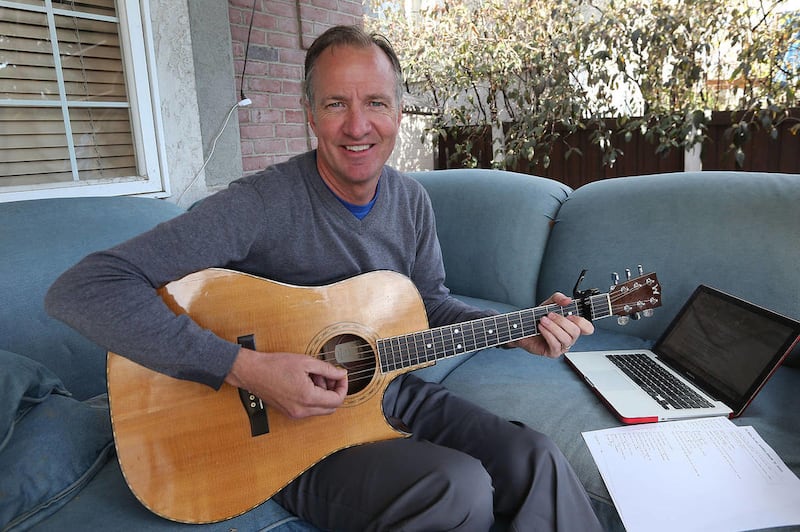

Eyestone, a relaxed man with a dry wit and a ready sense of humor, has brought his own style and talents to coaching. A longtime guitar player, he sometimes brings his guitar on team road trips and occasionally plays and sings for his athletes. At the end of every season he writes and then performs a humorous song at the team awards banquet that chronicles the season’s memorable moments and includes something about every athlete.

“Those are treasures,” says Ward. “I have copies of those songs from my freshman year. He performs the song and then hands out the lyrics.”

Eyestone has established what he hopes will become team traditions. The various groups of athletes train at various times, but they all come together one day a week — men and women — to run a team lap and then “celebrate, communicate and motivate.” If an athlete produced a performance the previous week that cracks the top 10 of his event on the school’s all-time record board — which hangs high on a wall in the field house — the team gathers for “the ladder ceremony.” A ladder is placed under the record board and the athlete climbs to the board as the team chants “Ladder! Ladder!” to remove the 10th athlete on the list and to place his name where it belongs on the list. The coach talks about the athlete whose name was knocked out of the top 10 and then about the athlete whose name has now attained top-10 status.

“It’s all about creating traditions, opportunities and motivation,” says Eyestone. “It’s something the other athletes can shoot for. They want to climb the ladder and get their name up there.”

Eyestone sits down with each of his runners at the start of the year to discuss a training plan. While many coaches produce one-size-fits-all training plans, his are tailored, as much as possible, to an athlete’s weaknesses and strengths.

“He is quite mindful of each runner and what’s best for him, all the way to the 30th runner,” says Ward. “He pays attention to everyone. He is confident that what he gives you will work. He’s done most of it himself and he’s got years of experience coaching. He’s seen what works and what doesn’t work and what works at different times of the season.”

Says Kotter, “Everyone loves Coach Eyestone. He is definitely an athletes’ coach and very approachable. He knows all his athletes well.”

For his part, the 52-year-old Eyestone, who once ran marathons at a 5-flat-per-mile pace, still runs five miles a day (at about a 6-minute clip) and occasionally accompanies his athletes on light runs — “usually after I set them up with a hard workout,” he says. Despite all those miles he piled up over the years, he has no aches or pains, and at 6-foot-2, he is still a spare 165 pounds, up from his gaunt 139-pound racing weight.

Years ago, after he signed his second four-year deal with Reebok, he realized he was “all in” with the running business. Any chance for another career was getting away from him. As a result, while sidelined by pneumonia for a time, he asked Wood to search for broadcast opportunities. Wood found them and it has led to a side career as a color commentator. Eyestone provided commentary for NBC’s 2008 Olympic coverage, and for a dozen years he did a handful of races annually for ESPN’s Race of the Month series before it was discontinued. He continues to do TV work, most recently the Chicago Marathon, but also the New York and L.A. marathons, among other races that occur on weekends when BYU doesn’t have a meet.

Eyestone, who has six daughters with his wife Lynn, also wrote a monthly column for Runner’s World Magazine for about a decade. “I was happy to be done with that,” he says. “It became my monthly albatross. The kids could tell when a column was due; I’d go to bed early, manifesting signs of depression. You can only write about marathon training for so long. I used up my good stuff the first two years. I was practically plagiarizing my own stuff.”

After almost 40 years in the running business, Eyestone is still all in. “It’s been a natural thing,” he says. “I guess it’s the 10,000-hour theory. You follow your expertise and do what you know.”

Doug Robinson's columns run on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. Email: drob@deseretnews.com