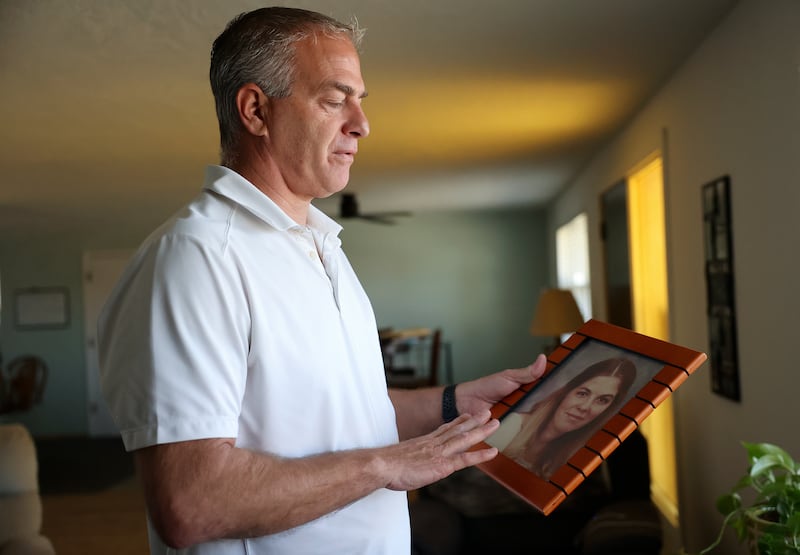

Matt Hunsaker remembers his mom, Maurine Hunsaker, as a woman who loved her family and was an amazing person — the kind of mom who was always at his baseball games and had ready a smile.

“She’s amazing, that’s all I can say. She’s amazing,” Matt Hunsaker said. “Who she taught me to be was great.” He said he has a lot of memories of her and that she “fought a lot to support her family.”

Maurine Hunsaker was 26 years old and working at a Kearns gas station when Ralph Menzies kidnapped and murdered her. Menzies was sentenced to death in 1988 and has now exhausted all his appeals. The state is seeking a death warrant. The court has ordered a competency hearing before the execution is to proceed. His lawyers claim he has vascular dementia.

Matt Hunsaker was 10 years old when his mother was brutally murdered in 1986. Those 10 years were “a short time to have memories with my mother,” he said, but he noted the family makes efforts to keep her legacy alive. “We visit her grave repeatedly and keep her memory alive. We make sure that any time he’s in the news and the focus is always on him, his rights, his appeals, I do my hardest to make sure that it’s reminded who he killed.”

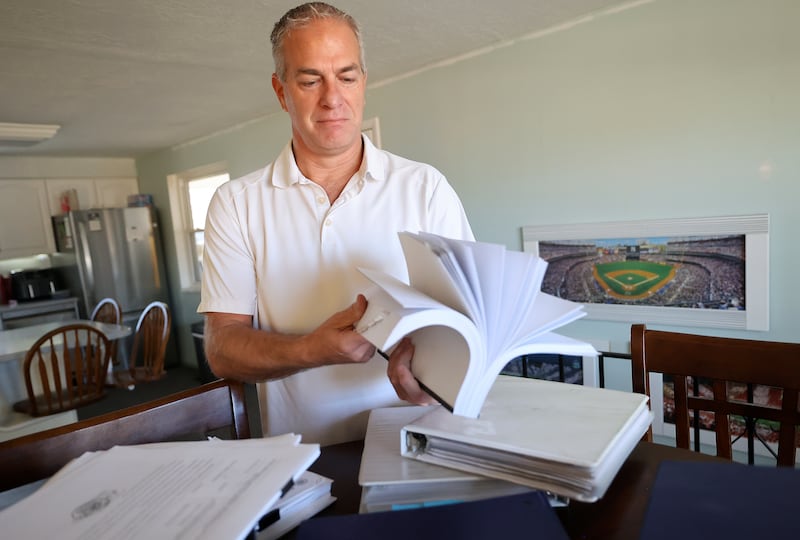

In the years since his mom’s death, Matt Hunsaker has found himself in court, in front of the Legislature and talking to the media while fighting for his mother’s memory and for justice. He finds it hard to estimate just how many hours he’s spent in the process — whether in court appeals or testifying against legislation seeking to get rid of the death penalty or even just researching death penalty laws.

“It’s 38 years of this. It’s hard. It’s hard on everybody, even the ones that were never there. The young kids that have no idea. They’re learning slowly,” Hunsaker said. As his children have grown older, they’ve become more exposed to what happened to their grandma.

“It’s all over the internet. They have Google,” he said. But what’s important to him is “trying to teach my kids the things that my mom taught me and the way that she raised me.”

Hunsaker wants 2024 to be the year that this case is resolved. He said he already has peace, even though it’s taken a long time, and he just wants the process to end.

Going in and out of court for decades takes its toll, and Hunsaker believes there are flaws in the process. “I respect and I understand that the system has to make sure everything is done correctly, but when someone’s guilty and undoubtedly guilty, they did it. There shouldn’t be 30 years of process.”

While Hunsaker believes there should be an appeals process, he thinks the process needs time frames built in, so families aren’t dragged through it time and time again.

Back in 1995, after the court stayed Menzies’ execution, Maurine’s mother, Betty Sudweeks, expressed her disappointment and told reporters, “Maurine had a very lovely family and a husband she adored. She had everything to live for. Mr. Menzies snuffed that out all at once. I just wish he had given her all the opportunities to live that he wants for himself.”

Sudweeks had been determined to be present throughout every step of the appeals process. She died in 2021 before the process ended. Now Hunsaker is trying to follow through on his grandmother’s wishes.

“Never in a million years do you want to have to bury one of your children, especially in a situation as this was. And I can only image how heavy this weighed upon my grandma all of her life,” he said. “And I know that my grandma was adamant that she wanted to see him executed.”

Whenever any news comes out about appeals, Hunsaker goes to court and to the media to make sure it’s known there’s a victim involved. “There’s multiple victims here. My mom is the main one and then us family that was also cheated out of what we had,” he said. “But I will always do what I can to make sure that the focus is on her.”

The current focus deals with Menzies’ competency. After the competency hearing, the court could either decide to move forward with execution (if he’s found competent) or if he’s found incompetent, it’s likely to be the end of the court process.

If the court finds Menzies incompetent, Hunsaker said it would be difficult for him, but it wouldn’t have a lasting effect because the process would be over. If the court finds him competent, he said, “it’ll be a fight for me because I believe that if it’s ruled that he is competent to be executed, I believe that they’re going to try everything that they can to appeal that.”

Hunsaker said he doesn’t think removing the death penalty from Utah law will ultimately stop the appeals process for families. Each year before the legislative session, he prays they won’t take it on.

“Every year, you just pray to God that they won’t drag the death penalty in this year. ‘Don’t do it, don’t do it,’” Hunsaker said.

When death penalty legislation has come up at the Capitol, he’s gone to hearings and asked if the state stops with capital punishment, will the appeals in his case end. He said the answer he’s gotten is they don’t know if the appeals process will end.

When Menzies was convicted in 1988, the jury could have voted for the death penalty or a life in prison. At the time, the prosecution pointed out that if Menzies was sentenced to life in prison, it was possible he could be let out on parole. Hunsaker’s concern continues to be what happens if the death penalty is off the table in Utah.

Will Menzies’ sentence be commuted to life without possibility of parole? Or will he be able to argue he should have life in prison instead, since that was the other sentence available?

Hunsaker said he has not been assured there wouldn’t be another series of legal proceedings where Menzies could argue he should have life in prison with the possibility of parole. Utah code does say if the death penalty is found unconstitutional, the court will sentence the person to life in prison without parole.

But would the state be able to commute a death sentence down to life without the possibility of parole if that sentence was not available at the original conviction date? “Those are my arguments that nobody can ever give me the answer to,” Hunsaker said, adding that he thinks he’d still end up back in court watching arguments over this question play out.

“I’m not against getting rid of the death penalty. I’m just 100% for not messing with my case,” he said. “Don’t go in here and try to feed the world and everybody that this is going to stop all the suffering and the pain and all the appeals because it’s not. It won’t stop the appeals for us.”

If the time comes when Menzies does face execution, Hunsaker said he will go, along with his younger brother, his dad and his older son. Everyone has their own reason for going, he said, and each has done a lot of soul-searching to get to that point.

Throughout the impending proceedings, Hunsaker wants people to remember the victim. “When it all comes down to it, the reason why we’re here is because he took my mom’s life.”